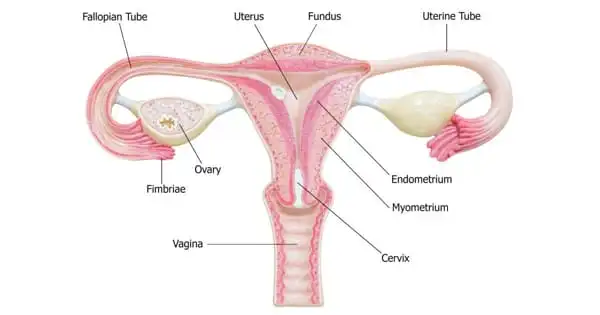

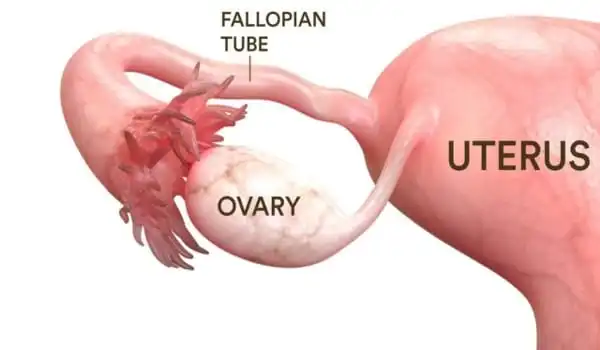

The fallopian tube is the location of fertilization, where an egg is transferred from the ovary once a month for the course of a female’s post-pubescent, pre-menopausal life, ready for fertilization by a sperm cell.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine have created a thorough “map” of the numerous cell types and gene activities within the highly specialized fallopian tube, paving the path for new research into infertility and other disorders affecting this organ, including some malignancies.

Using tissue samples from four premenopausal women, Saher Sue Hammoud, Ph.D., and Jun Li, Ph.D. from the Department of Human Genetics led a team from the University of Michigan to evaluate over 60,000 cells using single-cell RNA sequencing. They used the data to characterize the diversity of cells that comprise the fallopian tube, including the lining (the epithelium) and the deeper stromal layer, which contains immune, blood, muscle, and other cells.

Ariella Shikanov, Ph.D., of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Erica Marsh, M.D., of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and team members Nicole Ulrich, M.D., Yu-chi Shen, Ph.D., and Qianyi Ma, Ph.D., join Hammoud and Li. Their work is part of the Human Cell Atlas Seed Networks, a global effort financed by the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative to map all cells in the human body as a resource for a better understanding of health and disease.

In the premenopausal woman, the EMT process appears to be carefully regulated. One probable link to cancer is that when this group of cells is misregulated in certain unfortunate individuals, they may develop ovarian cancer. You have the tendency right there with EMT cells in the fallopian tube.

Saher Sue Hammoud

“It was previously known that there are around four epithelial cell types in the fallopian tube,” Hammoud explained. “We were able to uncover a deeper amount of heterogeneity inside these cells.”

They specifically identified ten epithelial cell subtypes, including four of the finger-like ciliated cells responsible for carrying the egg through the fallopian tube’s three portions before and after fertilization.

The cells within the fallopian tube are constantly changing, replacing themselves over time and altering in number based on a woman’s age, hormones, menstrual cycle, and the presence of disease. The researchers were able to identify which cells increased in quantity and which changed features, such as a high degree of inflammation, by comparing cells from women with healthy fallopian tubes to two samples from women with hydrosalpinx (conventionally known as a blocked fallopian tube).

“Some of the cells are the cause of the illness state, and others are the result, and now we know the patterns for individual cell types to figure out the molecular basis for that pathology,” Li explained.

Precursor cells in the tube and cancer connection?

The researchers also discovered that some of the fallopian tube cell subtypes they identified may operate as precursor cells, or cells that can regenerate several cell types in response to normal tissue turnover or to heal damage.

According to Hammoud, one of the most startling findings of the study was the detection of cells with markers for epithelial-mesenchymal transition, better known as EMT, a process not previously connected with the fallopian tube in which a cell might become malignant under specific conditions.

It turns out that the term “ovarian cancer” may be misleading. The current study adds to the growing body of data that ovarian cancer, the fifth greatest cause of cancer death in women, may have its origins in the neighboring fallopian tube.

“In the premenopausal woman, the EMT process appears to be carefully regulated,” she noted. “One probable link to cancer is that when this group of cells is misregulated in certain unfortunate individuals, they may develop ovarian cancer. You have the tendency right there with EMT cells in the fallopian tube.”

Additional information was obtained from the fallopian tube cells of women with hydrosalpinx, specifically that the condition may result in a type of scarring known as fibrosis. The implication is that for women who do not want their tubes removed, “you may consider treating them with anti-fibrotic medications such as those used to treat pulmonary fibrosis as a strategy to save their tubes during reproductive age,” Hammoud said.

In comparison to previous efforts, the current study gives far more precise information about cell kinds and functions in the tube for researchers interested in a variety of concerns about the normal female reproductive system. “This really is a basecamp from which to launch future investigations,” Li says, including ones looking at the effects of age, the menstrual cycle, hormone therapy, and ancestry on cellular diversity and disease pathology.