Laufskálarétt is an Icelandic horse breed. Icelandic horses are known for their five gaits (walk, trot, canter, tölt, and pace), making them highly valued for riding and show purposes. They are also known for their strength, endurance, and intelligence.

“It looks like the weather tomorrow will be good for us,” says Þórdís Anna Gylfadóttir as she studies the pink-hued sky. “When it’s a nice day, we have more people coming to the valley.”

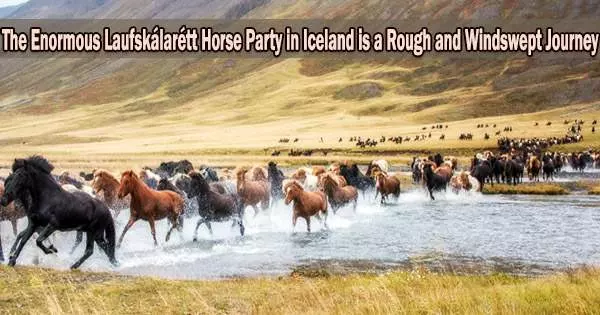

The Hjaltadalur valley seems peaceful, with little to suggest that thousands of people and hundreds of horses will travel to this isolated area in the northern Skagafjörður region the following day to watch the Laufskálarétt horse party, the largest horse-herding event on Iceland’s calendar.

And in Iceland, horse-herding is a big deal; the country has around 90,000 horses.

Iceland is extremely protective of its horses, who are renowned worldwide for their hardiness, placid temperaments, and thick manes. Icelandic horses are native to Iceland and have been bred there for over a thousand years.

The Icelandic horses are purebred and have few ailments because the bloodline is protected by stringent regulations on bringing other horses and equestrian equipment into the nation. Even the riding method is unique. There are five gaits: alongside the standard gallop, trot and walk there is tölt and flying pace, known as the “fifth gear.” Iceland’s riding school, Hólar University, is world-renowned.

Every year, horse farms will turn out their female mares and geldings for the summer to graze. The thoroughbred horses, which were initially introduced to the island nation in the 10th century, are free to wander the highlands.

Come September, when the temperature drops and the bitter Icelandic wind whips through the valleys, the horses are brought in for the winter.

Participants arrive in minivans, SUVs, and horse boxes to transport their four-legged steeds home, which is frequently up to 20 kilometers away. The event is a reason to celebrate, with traditional dried harfiskur fish, steaming meat soup, and lots of Icelandic liquor shared around.

Long into the night, the celebration goes on at farms all throughout the area, as well as in a nearby riding hall.

‘Amazing feeling’

“It’s hard to get together, because everybody lives quite far away from each other,” says Þórdís, who owns 40 horses. “And so this has become a legendary weekend event. Even if you don’t have horses in this corral, you come down anyway because it’s just tradition. It’s the most well-known corral in Iceland.”

It’s the fifth time Sæunn Kristin, a kindergarten teacher, will be riding in the corral with her 25-year-old horse Tungl (“moon” in Icelandic).

“I don’t have any horses here but it is just the most amazing feeling to ride out and help bring the horses back. They are these wild animals and to see them being able to roam is beautiful. And the feeling of riding, it just makes you feel free.”

This year, about 20 farmers are coming to gather the 500 or so horses that are dispersed over the hillsides. However, they are joined by vacationers from all over Europe who come to ride and assist in leading the horses up to the corral, where the animals are separated into their respective farms, across the river.

“All the horses are microchipped,” explains Atli Már Traustason, who is overseeing this year’s corral. He’s a farmer and horse-breeder, and has his own horses to escort home to Syðri-Hofdalir, his farm.

“But each farmer knows his own horse, by name, by face. I know every one of my horses. I trained all of them from foal to grown up; I know all of their individual characters. But we also use branding, a tag on their ear, to identify them.”

Before the sorting begins, the horses must be cajoled from their grazing terrain.

Riders, both farmers, Icelanders and tourists, set out at 12 p.m., to begin ushering the horses into one big group. The farmers sprint through the plains herding the animals while they are protected from the bitter weather by wearing thick jackets, gloves, and helmets while mounted on their horses that have been kept over the summer for riding.

Icelandic sheepdogs expertly assist their owners in rounding up the several horses and assisting them in a coordinated river crossing as they bark at the horses’ ankles.

Microchipped horses

The hundreds of horses are herded into a fenced-off field before being led in small groups to the main pen after traveling approximately three kilometers in a line up a thin dirt track to the Laufskálarétt corral. An enormous pie-shaped structure is formed by the concrete walls that fan out from the central holding and are each labeled with the name of the farm.

“All the farmers help each other out,” Atli continues. “You identify your horse, and then you work to round it into your pen.”

Each horse is sorted, some more easily than others, to the sounds of shouts, whistles, neighs, and whinnies that resound throughout the valley. In the past, to drive a troublesome horse into a pen, farmers would have to jump upon its back, and accidents weren’t unusual. Around 15 years ago, the farmers came together to devise a strategy to make the process smoother.

Atli, who is wearing an earpiece, says, “It’s much better now. And, of course, now we have technology. We wanted to find a way to protect people and horses, and so now we have small groups to get each horse into the right farm pen.” The horse’s microchip is scanned via a phone app into a national horse database, so there are no mix-ups.

A group of men wearing flat caps and wearing traditional woolen sweaters have gathered next to the pig enclosure and are singing traditional Icelandic songs as the farmers are hard at work.

As more people join in, the group grows and soon the opera drowns out the horses. Viking drinks in hand. Some of the horse boxes have been converted into temporary cafes, replete with picnic seats and serving hot soup, rye bread, and coffee to the masses that have gathered inside to stay warm and catch up.

Drinking and riding

Over the past years, the corral has become more popular among tourists. Annabelle Loch flew from Niedernhausen in Germany specifically to ride in the event.

“My friend told me about the roundup and I found a farm that offered to take tourists to participate. I’ve never seen so many horses in one place, and it was amazing to see all the different colored horses riding across the river. I couldn’t believe how close they were running to us too.”

She adds: “It was also interesting to see how much the Icelandic people could drink without falling off their horses.”

Horses are part and parcel of the Icelandic way of life, particularly here in the remote north.

“It’s a tradition here in Skagafjörður to own horses,” Atli points out. “Most people here have at least 10 horses. It’s actually more unique if you don’t own a horse.”

By 3.30 p.m., the center of the corral pen is empty. “Every horse has been accounted for,” Atli reports. “And nobody is missing a horse.”

Now, the party can really begin.