The asteroid that wiped out nearly all dinosaurs hit Earth in the spring. After analyzing the remains of fish that died shortly after the impact, an international team of scientists from the Vrije Universiteit (VU) Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Uppsala University (Sweden), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium), and the ESRF, the European Synchrotron (France) determined when the meteorite crashed onto the Earth. Their findings have been published in the journal Nature.

The so-called Chicxulub meteorite crashed into the Earth around 66 million years ago, in what is now Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, bringing dinosaurs to an end and the Cretaceous period to an end. Scientists are still baffled by this mass extinction, which was one of the most selective in the history of life: all non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, ammonites, and most marine reptiles perished, while mammals, birds, crocodiles, and turtles survived.

A group of scientists from the Vrije Universiteit, Uppsala University, and the ESRF have now shed light on the circumstances surrounding the various extinctions. The answers came from the bones of fish that died moments after being hit by a meteorite.

When the meteorite collided with Earth, it shook the continental plate and created massive waves in bodies of water such as rivers and lakes. These displaced massive amounts of sediment, engulfing and burying fish alive, while impact spherules (glass beads of Earth rock) rained down from the sky less than an hour after impact. Today, the Tanis event deposit in North Dakota (United States) preserves a fossilized ecosystem that includes paddlefish and sturgeons, both of which were direct victims of the event.

Bone cell density and volumes in all studied fishes can be traced back multiple years and indicate whether it was spring, summer, autumn, or winter. We saw that both cell density and volume were increasing but had not yet peaked during the year of death, implying that growth abruptly ceased in the spring.

Dennis Voeten

The fossil fishes were exceptionally well preserved, with almost no signs of geochemical alteration in their bones. Melanie During, lead author of the publication and researcher from Uppsala University and the VU Amsterdam, went onsite to excavate the valuable specimens: “It was obvious to us that we needed to analyze these bones to get valuable information about the moment of impact,” she explains.

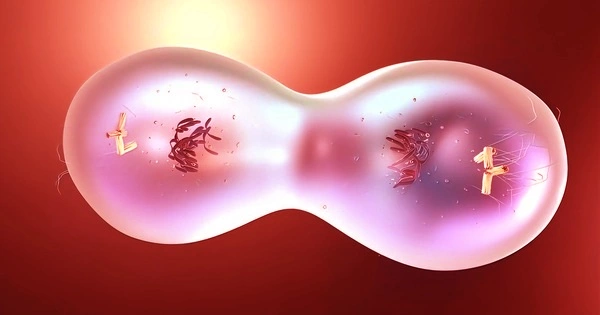

The team brought a partial fish specimen and representative sections of the bones to the ESRF, a particle accelerator that produces the world’s brightest x-rays, and performed high-resolution synchrotron X-ray tomography.

The ESRF is the ideal tool for studying these types of samples, and the facility has developed unique expertise in palaeontology over the last two decades. “Thanks to the ESRF’s data, we discovered that the bones registered seasonal growth, very similar to trees, growing a new layer on the outside of the bone every year,” explains Sophie Sanchez of Uppsala University, a visiting scientist at the ESRF.

“The retrieved growth rings not only captured the life histories of the fishes but also recorded the latest Cretaceous seasonality and thus the season in which the catastrophic extinction occurred,” says senior author Jeroen van der Lubbe of the VU in Amsterdam.

The X-ray scans also revealed the distribution, shapes, and sizes of bone cells, which are known to change with the seasons. “Bone cell density and volumes in all studied fishes can be traced back multiple years and indicate whether it was spring, summer, autumn, or winter. We saw that both cell density and volume were increasing but had not yet peaked during the year of death, implying that growth abruptly ceased in the spring” According to Dennis Voeten, a researcher at Uppsala University.

In addition to synchrotron radiation studies, the team used carbon isotope analysis to determine a fish’s annual feeding pattern. The availability of zooplankton, its preferred prey, fluctuated seasonally and peaked in the summer. This temporary increase in ingested zooplankton enriched the fish skeleton with the heavier 13C carbon isotope compared to the lighter 12C carbon isotope. “The carbon isotope signal across this unfortunate paddlefish’s growth record confirms that the feeding season had not yet climaxed — death came in spring,” claims During.

The findings will help future research into the selectivity of the mass extinction: it was spring in the Northern Hemisphere, so organism reproduction cycles were starting, only to be abruptly stopped. Meanwhile, in the Southern Hemisphere, it was autumn, and many organisms were likely preparing for winter. In general, it is well understood that organisms exposed died almost instantly. Those who sought refuge in caves or burrows while hibernating were far more likely to survive into the Paleogene.

“Our findings will help to explain why most dinosaurs died out while birds and early mammals survived,” During concludes.