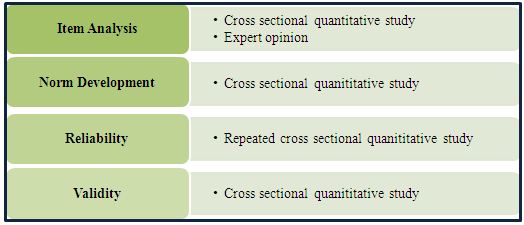

Children differ qualitatively from their peers in respect to their intellectual abilities. These qualitative differences may influence a child’s subsequent independence in his/her life as well as family and society. But it is unfortunate for those parents whose expectations and hopes are shattered by the birth of children at high risk and/or children with developmental delays. Psychologists and educators are systematically utilizing scientific methods to measure individual differences among people. Bangladesh has a dreadful need to improve and update the standard of existing assessment condition which is an integral part of instruction, as it determines whether or not the goals of education are being met. The study aims to standardize the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (Fifth Edition) in Bangla for use in urban Bangladesh in order to fill up the gap in the psychometric sector. Hence, the research was designed to complete the criterion for standardizing the psychological ability test. Thus, the present research was conducted in four steps (item analysis, norm development, reliability and validity) as a part of standardization process of an intelligence scale. For the calculation of norm, the study has considered students from six divisional metropolitan cities to represent Bangladesh. After translating the original SB5 into Bangla, item analysis, as a first step of standardization process, was carried out through SB5 tool kit among the 330 students of 11 age levels (6-16 years) to scrutinize the strengths and weaknesses of the test items. In order to retain the original theme, the items were replaced with native content/symbol or object, made the items culture friendly, and often retranslated the questions for better understanding of the students. The overall reliability coefficient (α=0.84) suggests that there is high and increasing correlation among the items. Based on the raw scores obtained from the ten subtests, age norm was calculated separately for the 11 age groups. The norms were developed on 3300 students from the raw scores that were obtained in the record form. Their raw scores were ranked in 19 scores group and then the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) was constructed from the ranks. The IQ ranges of SB5-BD for age norm of 6 to 16 years children are 86 to 152. Test-retest reliability was constructed based on the scores obtained twice with the same instrument on the same individual with one week of time interval on 330 students. Test statistics suggests that there was no significant difference between the IQ obtained in the first week and again second administration that was obtained a week later. As a measure of reliability, the correlation coefficient between the first and second administration of the tests were 72%, 76%, and 75% for Non verbal IQ, Verbal IQ and Full Scale IQ respectively. In order to examine the criterion related validity SB5-BD and WISC-R (Bangla Version) were administered on the same participants. The study considered 90 students from three age groups. Findings reveal from the descriptive statistics that there were significant similarities between the IQ scores obtained by the two test administration. To find out the differences in IQ for test validity, the SB5-BD was administered on normal and students with special needs. Result indicates a low mean and standard deviation among students with special needs. The P value suggests that there is statistically significant difference between the IQ obtained by normal and students with special needs. Finally, the study extensively accomplished the four steps and standardization process successfully completed. Through this study, the standardized SB5-BD is regarded as the renovative and contemporary assessment scale in the field of psychometric testing for 6 to 16 years children in urban Bangladesh and hope; it will accelerate all the stagnant issues related to the benefit of human kind, above all for the children with special needs.

The supreme adaptive resource of human being is his intelligence – his superior intellectual ability for wisdom, interpretation and prediction. By the blessings of this resource, as a species, he dominates on many facets of his environment and establishes his superiority over other associates of the living kingdom. Besides, this supremacy may be flattened and ruin the individual’s spontaneous autonomy if an individual is born with or acquire developmental delays. The pursuit of an efficient and accurate way to identify and compare this ability in individual is an ongoing trends and its consequence in the field of education and development is apparent and undeniable. Thus, scholars of the earlier period explored intelligence to categorize the individual differences and their abilities but there were variations among the experts in defining intelligence in a single concept.

Hence, along with the above perspective, the present study would be considered as the Hallmark reformation in the field of educational development in Bangladesh. Consequently, the study is an efficient and renovative effort to establish a yardstick for the benefit of human kind, above all children with special needs. This chapter briefly presents five issues: firstly, it states the understanding the concepts of intelligence and individual differences ; describes the psychometric tests, secondly, it explains the necessity of assessing intelligence, thirdly, the chapter highlights the psychometric and contemporary device for intelligence test, fourthly, it portrays the present testing and disability scenario: international and Bangladesh perspective, finally , this chapter depicts the rationale and objectives of the study.

Understanding the Concepts– Intelligence and Individual Differences

Intelligence is versatile and often changed notion with referred to as Intelligence Quotient (IQ), cognitive functioning, intellectual ability, and aptitude, thinking skills, general ability and intellectual development (Logsdon, 2011). These multifaceted terminologies are being used throughout the study to comprehend the unique criteria of intelligence. Everyone assumes that he or she knows intelligent performance when it is observed, but when it is tried to define, the ambiguity of the trait becomes apparent (Daniels, Devlin & Roeder, 1997). With various common consents of researchers’, numerous definitions of intelligence have been proposed before the twentieth century. Besides, various approaches to human intelligence also have been adopted of which few have been explained to validate the present research study.

The unitary concept of general ability or intelligence emerged from the definitions of Binet and Spearman. In their studies, they created a statistical technique called factor analysis to explore their approach. From the studies, they were able to report that about half of the variance in tests of mental ability was due to the general factor (Kaplan & Sacuzzo, 2001). This general or global intelligence is commonly referred to by the single italicized letter, g (Spearman, 1927). An alternative conception of intelligence is that cognitive capacities within individuals are a manifestation of a general component, or general intelligence factor, as well as cognitive capacity specific to a given domain such as reading, mathematics and writing (Miller, 1991). Even though at present intelligence is viewed in a multidimensional concepts as emotional, multiple, social, artificial intelligence etc. In this study, the author intends to utilize the general intelligence as a global perspective to justify an individual’s intellectual capabilities that influence his /her overall developmental condition particularly academic and social performance.

The concept of individual differences was gaining popularity around the world at the same time as Binet’s work, spurred by the movement towards universal compulsory education in many countries. At the time, many psychologists were addressing the problem of how to identify children who would have success in education (Thorndike, 1990). Thinking on the same aspect on intelligence, the pioneer of intelligence testing, Binet (1905) reflected the opinion that “In intelligence there is a fundamental faculty, the alteration or the lack of which, is of the utmost importance for practical life. This faculty is judgment, otherwise called good sense, practical sense, initiative, the faculty of adapting one’s self to circumstances.” A heightened focus on defining and assessing intelligence began in the 1800’s as part of attempts to classify between various levels of mental retardation and mental illness using psychological tests (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). Viewed broadly, the scientific and professional organization, the American Psychological Association (APA, 1996) defines intelligence with the concept that “Individuals differ from one another in their ability to understand complex ideas, to adapt effectively to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning, to overcome obstacles by taking thought.” These definitions seemed to have an orientation to academic learning and performance along with emphasis on abilities that are valued by one’s culture. As cultural differences play a vital role in forming an individual’s life style, it is essential to assess how different cultures make sense of the world in terms of the meanings that represent the mind and within which the concept of intelligence is defined (Bouchard & Segal, 1985).

Therefore, at present the most acceptable definition of this concept is “Intelligence is not a single, unitary ability, but rather a composite of several functions. The term denotes that combination of abilities required for survival and advancement within a particular culture” (Anastasi, 1992; 1997). Thus, more recent definitions have been moving toward practical definitions with a view as to how the person functions in the real world as well as in traditional academic settings (Wagner, 2000). Aspects of the definition that seem to have wide appeal include learning speed, adaptability and ability to perform in the society successfully.

Hence, research in intelligence is active as well as robust, and this study investigates the power of intelligence related to educational, social learning and performance of both normal and children with special needs. Further, a great number of researches still have been conducted through various ways, using many theoretical viewpoints and establishing a variety of results to define and measure intelligence throughout the year. Despite the variety of terms of intelligence, the most influential approach to understanding intelligence is based on psychometric testing. In fact, the technical term for the science behind psychological testing is psychometrics (Neisser, Boodoo, Bouchard, Boykin, Brody & Ceci, 1996).

Psychometric Tests

Psychometrics is the field of study concerned with the theory and technique of psychological measurement, which includes the measurement of knowledge, abilities, attitudes and personality traits. The field is primarily concerned with the study of differences between individuals. It involves two major research tasks, namely: (i) the construction of instruments and procedures for measurement; and (ii) the development and refinement of theoretical approaches to measurement. (Kline, 1999).

The first psychometric instruments were designed to measure the concept of intelligence. The best known historical approach involves the Stanford –Binet intelligence scale, developed originally by the French Psychologist Alfred Binet. Contrary to a fairly widespread misconception, there is no compelling evidence that it is possible to measure innate intelligence through such instruments, in the sense of an innate learning capacity unaffected by experience, nor was this the original intention when they were developed.

Similarly, psychological testing is a field characterized by the use of samples of behavior in order to assess psychological construct(s), such as cognitive and emotional functioning, about a given individual. The burning issue at present in the field of psychology is the assessment (referred to as test, evaluation, measurement, scale, battery etc.) of an individual’s behavioral characteristics (e.g. ability of intelligence, emotional functioning, interests or attitudes, aptitude, normal, abnormal personality and achievement) through psychological tests. Psychological assessment is also referred to as psychological testing, or performing a psychological battery on a person. This is also a process of testing that uses a combination of techniques to help arrive at some hypotheses about a person and their behavior, intelligence, personality and capabilities (Framingham, 2011). Assessment can range from the formal–standardized to the informal–teacher made assessments. Standardized tests are usually considered as formal tests. These are developed by testing organizations and administered in clinics and class room settings and scored in a consistent manner. In this aspect, the test scores are interpreted with regards to a norm or criterion, or occasionally both. The norm is established independently, or by statistical analysis of a large number of participants (Mellenbergh, 2008). There are several categories of psychological test, such as achievement test, aptitude tests, intelligence tests, neuropsychological tests, occupational tests, personality tests etc (Charles, 1996).

Table 1

Several Categories of Psychological Tests (At a Glance)

| Test name | Setting /Used in | What Measure | Example |

| Achievement test | Educational | Achieved knowledge | General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE)Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) |

| Aptitude test | Employment | Aptitude | Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) |

| Intelligence test | Clinic / School | Potential/ Intelligence | WISC-R, SB5 |

| Neuropsychological | Clinic | Deficits in cognitive functioning | Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) |

| Occupational | School / Office | Interest in career | Occupational Interest Profile |

| Personality | Forensic | Personality | Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) |

These psychological tests are often discussed in terms of the dimensions as they measure. They refer to these as dimensions because they are broader than a single attribute or trait level. Often these types of tests measure various personal attributes or traits. (Hersen, 2003). Professionals refer to these tests in various ways. Sometimes they refer to them as tests of maximal performance, behavior observation tests, or self-report tests. Sometimes professionals refer to tests as being standardized or non-standardized, objective or projective. Other times they refer to tests based on what the tests measure. (Rasch, 1980:1960). Even though, from above among the various psychological tests, the study focuses only on a standardized norm-referenced intelligence test for assessing the intellectual ability of an individual. The educational need and advanced educational programs for identifying and classifying children with limited intellectual abilities and gifted learners has been an important force in the development of psychological tests. These tests also play an especially important role in special education. They can be useful for identifying an expected level of academic performance and also in helping school professionals design Individual Education Plan (IEP) for students with special needs (Sattler, 2001). Thus, the testing movement is the consequence of a need to determine the intellectual, sensory, and behavioral (personality) characteristics in individuals and hence, intelligence as a significant factor could only be established until a person’s ability is assessed.

The Necessity of Assessing Intelligence

Assessing intelligence is a complex process but has become an established practice in psychological testing because of its potential effects on individuals’ lives. Measures of a child’s intellectual abilities are considered one part of what is referred to as the ‘Fours Pillars of Assessment’. Along with behavioral observations , interview and informal assessment, intelligence testing provides an assessor with information into a child’s overall level of functioning , as well as specific abilities (Sattler, 1992). However, intelligence tests provide information about a child’s abilities in two main ways that the above stated other methods do not. Firstly, it provides a standardized or norm referenced framework. Secondly, aptitude test has been found to be correlated with performance in both school and work environments (Sattler, 1992, Anastasi & Urbina, 1997).

Children differ qualitatively from their peers in respect to their intellectual abilities. Besides, these qualitative differences may influence a child’s subsequent independence in his/her life as well as family and community. But it is unfortunate for those parents whose expectations and hopes are shattered by the birth of children who are at risk or children with developmental delays. It is no secret that the number of children with special needs has dramatically increased in the past decade worldwide (Reschly, Tilly & Grimes, 1999). Therefore, comparisons between individuals, as well as intra-individual performances can be made for the purpose of placement or identifying special education needs using these tests. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (Text Revision) and American Psychiatric Association (APA), the aim of assessment is to gain insight into an individual that will aide in the decision making process with regard to screening, problem solving, diagnosis, therapy, rehabilitation, progress evaluation and to gauge the necessity for a complete battery (DSM-IV-TR & APA, 2000). Measuring intelligence is based on the fact that children become more capable mentally as they advance in age. The upper limit is reached in adolescence. Intelligence tests show that intellectual growth is rapid in infancy, moderate in childhood, and slows down in youth (Cahan &Cohen, 1989).

Thus a prerequisite criterion for the placement of such children either in mainstream or special school is to quantify their intellectual level that necessitates the measurement of intelligence through intelligence scale in accordance with their age, and sex. (Neisser, 1998). This comprehensive assessment will assist a professional to justify a child’s strength and weakness to overcome his delays. Accordingly, the goal of this research was not to categorize children with a single score but to pinpoint a child’s intellectual level along with other multidimensional factors such as age, sex, culture. Most significantly, Binet had the similar notion to identify children in the schools who required special educational needs. His intention was not to use IQ scores as a general device for ranking all children according to intellectual ability (Binet & Simon, 1905). Binet’s scale had a profound impact on educational development throughout the world. However, in spite of its constraints, the educators and psychologists utilized the scale worldwide with its actual value.

Based on the above pragmatic demands it can be traced that assessing intelligence among other individual traits has created an outstanding platform that depicts a person’s general level of intellectual capability, which is significant for the life of a human being. Moreover, the success of educational system in advanced countries has been owing to the development and utilization of standardized psychological testing of abilities of students. In this aspect, psychologists and educators are systematically updating and standardizing various psychometric and contemporary tests for the last century to measure individual differences among people.

The Psychometric and Contemporary Device for Assessing Intelligence

Ever since Alfred Binet’s great success in devising test to distinguish intellectually challenged children (terminologies used earlier were idiot, moron, imbecile, mentally retarded, mentally handicap, and intellectually disabled, intellectual impairment) from those with behavioral problems, psychometric instruments have played an important part in European and American life. Standardized tests are commonly used for historic, regulatory and practical reasons. A variety of historical trends, actual strengths, educational policies and commonly offered arguments justify the use of standardized tests. Tests are used for many purposes, such as selection, diagnosis and evaluation. Many of the most widely used tests are not intended to measure intelligence itself but closely related to construct scholastic aptitude, school achievement and specific abilities etc. Such tests are especially important for selection, decision and placement purposes (Flanagan, Genshaft & Harrison, 1997). Besides, standardized tests have been historically promoted as “objective” in the sense that the examiner’s biases would not influence the results (Domino, 2000). Moreover, psychologists, clinicians are routinely and traditionally trained in administering standardized tests due to the historic belief that standardized assessment is better because they are more formal and objective than other kinds of assessment, which are often named as “informal,” implying “less objective.” (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). Therefore, selecting the most appropriate test for a given child or situation can be a challenging task.

A review of the last 10 years of Mental Measurements Yearbooks (MMY) indicates an increase in the number of intelligence tests that can be used for young children. A few well known individually administered intelligence tests are as follows: Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5) (Roid,2003),Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) (Wechsler, 2004), Slosson Full-Range Intelligence Test (S-FRIT) (Algozzine, Eaves, Mann & Vance, 1993), Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT) (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993) and Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities (WJ III COG) ( Woodcock, McGrew & Mather, 2001), Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales (RIAS) (Reynolds, 2003). These tests are being used in evaluating intelligence and /or cognitive abilities in schools as well as assessment centre for identification purposes. In addition to this, the tests are developed for norm on large sample sizes and justify the age appropriate intellectual ability (Chang, 2008).

Researchers have different opinions on using these tests for assessment purposes. Along with varied opinions on the use of tests, the experts’ have come to a common consents and supports that the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, Fifth Edition is a sole contemporary device with a rich tradition since its inception in 1905 till date. Through various editions, this assessment scale is being used throughout the world. Other strengths of SB5 include its appealing materials and cognitively appropriate tasks. Besides, psychometric properties of the test at the school age, and its comprehensive subtests are considered as other strengths to find out children’s intellectual development in both verbal and nonverbal domains (Ford & Dahinten, 2005). Bracken and Nagle (2007) also suggested the use of the SB5 to assess the cognitive abilities of children as young as school age due to its superior psychometric and qualitative characteristics. Based on its popularity, usability and standard for intelligence measurement, SB5 is acknowledged and considered as the paramount instrument to serve the purpose of the present research. It is to be mentioned that the American Educational Research Association [AERA], American Psychological Association [APA], & National Council on Measurement in Education [NCME], (1999) have highly recommended the use of SB5 as the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Though several psychological tests have received prominence, many current innovations were derived only from the Binet-Simon scale. With regard to the current standard for educational and psychological testing, the SB5 has earned a leading position in the field of intellectual assessment. This scale is an individually administered assessment of intelligence and cognitive abilities. The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition (SB5), a direct descendent of Terman’s adaptation of the Binet test developed more than 100 years ago, is used in the educational setting. The SB5 is comprised of five composite factors representing two domains as nonverbal and verbal each having five testlets with a total of ten subtests (Roid, 2003) (reviewed and discussed in the chapter two and three ) .

Present Testing and Disability Scenario: International and Bangladesh Perspective

Formal and systematic measurement of intelligence, begun with the French psychologists Binet and Simon at the beginning of the 20th century, heralded the modern era of psychological testing. In subsequent years, tests to measure aptitude, personality and educational achievement were developed. The need to assess various abilities of a large number of army recruits at the beginning of World War I in 1917 gave a significant boost to psychological testing (Gregory, 2007). In the 21st century, psychological testing is a big trade in developed countries especially in America. There are thousands of commercially available, standardized psychological tests as well as thousands of unpublished tests. Approximately 20 million Americans per year were taking psychological tests (Goldman & Saunders, 1995). Today, psychological testing is a part of the American culture. Psychological tests are in use everywhere. The previous tests are regularly used in the school system as tools in making placement decisions. Current research provides information that supports the relationship between achievement and intelligence tests. One of the most significant and controversial uses of psychological testing in the 21st century has been a result of the ‘No Child Left Behind Act’ of 2001 (NCLB Act). The NCLB Act contains the strategies for improving the performance of schools—strategies that were intended to change the culture of America’s schools by defining a school’s success in terms of the achievement of its students (U.S. Department of Education, 2004). While tests have always played a critical role in the assessment of student achievement, the NCLB Act requires that students be tested more often and relies on test scores to make more important decisions than in the past. On the contrary, education reform in the United States since the late 1980s has been largely driven by the setting of academic standards for what students should learn and be able to do. These standards can then be used to guide all other system components. The standards-based reform movement describes for clear, measurable standards for all school students. Expectations are raised for all students’ performance. Along with norm-referenced rankings, the performance of all students is expected to be raised. Curriculum, assessments, and professional development are aligned to the standards.

Standards-based school reform has become a predominant issue facing public schools. (Popham, 1999). Besides, the largest Flynn effects appear instead on highly g-loaded tests such as Raven’s Progressive Matrices. This test is very popular in Europe; Raven’s test plays a central role in recent analyses of the worldwide rise in test scores. (Flynn, 2007). Hence, the Flynn effect is coming to an end, at least in Western Europe. Recent studies in

Scandinavia show intelligence test scores plateauing and arithmetic scores dropping. Far from being surprised, Flynn has been expecting as much. Since the social condition varies from country to country, it is significant to underpin the context of the diverse world (Flynn, 2007, & Collingwood, 2008).

In relation to the worldwide present scenario of psychological and other testing, Bangladesh is still left behind in the testing pathways. Until recently, most commonly cited disability prevalence rate has been the World Health Organization (WHO), which estimates that approximately 10% of the world’s population suffers from disabilities. In Bangladesh context that estimation would interpret as approximately 15 million people with disabilities based on 15th March, 2011 census. Action Aid Bangladesh based on 5 locations of 4 districts cited that approximately 12 million people (14% of the total population) require some form of immediate service due to disability related issues. (Action Aid Bangladesh, 1996). However, lack of quality data about those with disabilities makes addressing their needs difficult. Besides, according to ICDDR, B and core donor AusAID, “Unless international development programmes are inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities, achieving the UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG) is not possible”. In assistance with University of Melbourne in 2009, ICDDR, B developed a Rapid Assessment of Disability (RAD) toolkit for use by governments, NGOs and other organizations. This toolkit is easy-to-use, comprehensive way to measure disability prevalence, quality of life, social participation, access to and effectiveness of related development programs. The toolkit contains a four-part questionnaire in collaboration with Australian and Bangladeshi disability organizations and service providers. (Keeffe, Baker, Booth, Goujon, Edmonds, Huq & Quaiyum, 2011). On the other hand, the WHO has designed a set of Disability Assessment Schedules (known as the WHO-DAS) which have a long series of activity and participation based questions. Moreover, since the formal or mainstream schools run by the government, do not have overall disability programmes or activities at all, very few NGOs are being set to provide the programmes of identification, assessment, placement and decision making for leveling the degrees and type of the disabilities (Choudhuri, Alam, Hasan & Rashida , 2005). Thus with the above discussion till to date assessment plays a central element in the overall quality of teaching and learning in education. It also serves for the purposes of occupational prognosis, for clinical diagnosis, as well as psychological research and theorizing (Devlin, Feinberg, Resnick, & Roeder, 1997; Herrnstein & Murray, 1994). At the end of 19th century a few psychologists and educators have taken the initiative to standardize and develop non-standardized need based assessment scales which at present is outdated with time. Therefore, no disability prevalence data, the absence of reliable and consistent data on the magnitude and educational status of children with disabilities makes it difficult for educators, policy-makers and programmers to understand the nature of the problem and identify possible solutions.

Rationale of the Study

Appropriate stimulation in childhood occupies one of the most important platforms that influence normal development. Likewise, children use different modes in making sense of their experience and the world around them. They also acquire set of standard norms, knowledge, skills and attitude which the society demands for their existence. In this context, education (also called learning, teaching or schooling) in the universal sense is any act or experience that has a formative effect on the intelligence, character or physical ability of an individual. In its practical sense, education is the process by which society deliberately transmits its construct ability, knowledge, skills and values from one generation to another.

Globally, the enactment of legal issues related to compulsory and quality education would ensure a positive and desirable change in all aspects of an individual’s development. Based on the philosophy of Public Law 107-110 (2001), No Child Left Behind (NCLB) is a comprehensive plan in USA to reform schools, change school culture, empower parents and improve education for all children as well as improve instruction in high-poverty schools. Further the law ensures that poor and minority children also have the same opportunity as other children to meet the challenging academic standards. This law has brought sweeping changes to education across the world. Moreover, the recent implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLBA, 2002); the government of the United States mandated that all school-age children be tested for educational progress. In order to execute the mandate of NCLBA, along with the assessment provision, the need for translation and adaptation of test would eventually lead to assess student from multicultural and multilingual context (Allalouf, 2003 & Chang, 1999; Mathews, 2003).

Similarly, with the growing interest in cross-cultural research and evaluation, the interest in testing is not limited only in education but also in other fields. Such as psychological, vocational, career planning, selection and international comparative studies. The result of this interest is a boon for psychometrically equivalent, multi-lingual versions of assessment instruments. With the increasing demand for the use of psychological tests in various cultures and countries, the need for translation and adaptation of the test is of main concern. It is also apparent that the test adaptation is appropriate and significant.

In order to re-affirming the vision of Education For All (EFA), it is stated in the World Declaration made at Jomtien (1990) as: “All children, young people and adults have the human right to benefit from an education that will meet their basic learning needs in the best and fullest sense of the term” . With a view to ensure quality education as a human right , assessment should be considered as an important prerequisite to determine a student’s ability. It will enable the teachers to gear up and tap each individual’s talents and potentialities, so that they can benefit from education and improve their lives and transform to their societies. In accordance with the international commitments and legal acts, Bangladesh government has taken a positive initiative through the National Education Policy 2010 by Ministry of Education. This policy has highlighted the improvement of education system by including students with special needs in mainstream schools. It is unfortunate that in order to maintain the standard of the education system, the policy has not given any emphasis on screening and assessment of students’ intellectual ability. It should be mentioned that, according to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report in 2011, the ranking status of Bangladesh for literacy is 163 and literacy rate is 55.9 %.

In advanced countries the decision for placement of children in regular classroom or special classes is prioritized through a standardized comprehensive individual assessment of the children’s needs. The use of such psychometric tests also facilitate teachers in educational planning by providing approach to determine possible teaching learning strategies, which is regarded as a major initiative in order to ensure the goals for achieving education for all. Similar to many other low income countries, at present in Bangladesh, there have been no attempts to conduct regular national disability prevalence survey by the national statistical agency, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). The evolution of educational systems for children with special needs started from the introduction of special education in low income country like Bangladesh a long time ago. Over the time, the concept of disability as a social issue rather than a medical issue has become more understood and therefore the concepts of education systems also have been changed and developed towards as an integrated system and more recently an inclusive system, in accordance with local socio-economic and cultural conditions (Choudhuri et al., 2005).

The study Educating Children in Difficult Circumstances states that 8% of children with disabilities in Bangladesh are currently enrolled in various educational institutions (ESTEEM, 2002). Of these, 55% had physical disabilities, 13% were visually impaired, 12% were hearing and speech impaired and 10% had intellectual disabilities. About 68% of enrolled children with disabilities were in government and private primary schools and 15% were in pre-primary educational settings. About 48% were seeking formal education, 23% were in integrated schools, 15% in special education and 5% in inclusive education. Among enrolled children with mild and moderate disabilities, 79% are enrolled in formal educational settings. Of those with severe and profound disabilities, 83% were enrolled in special education. Nearly, 74% of those who are currently not enrolled in any form of education expressed a keen interest in receiving education (ESTEEM, 2002).

These educational systems are being practiced for children with special needs with few numbers. Likewise, the government’s Department of Social Services (DSS) is operating 5 special schools for children with visual impairment, 7 for children with hearing impairment, 1 for children with intellectual disability. The DSS is also operating a total of 64 integrated schools for blind children in 64 districts. NGOs are operating many special and inclusive education centers but there is no reliable data available on the number of schools that they operating (Choudhuri, et al., 2005). Although school enrolment (80%) is increasing at a fast rate, but the enrolment of children with disabilities is extremely low. Children with disabilities are often marginalized in mainstream schools as a result of negative attitudes towards them. A lack of child-centered approaches in education and the physical inaccessibility of schools are other reasons for low enrolment. In addition, some children with special needs are being enrolled into the mainstream education system by default. Some of them transferred from integrated and or special education systems (primarily visual impaired students) while a few make their way to the mainstream education system directly due to self- initiative and interest. Moreover, there are more than a million primary school-age children with assorted disabilities and disadvantages, but without access to basic education. The major shortcomings are due to the lack of educational reformation, improper implementation of the existing education policy and ignorance of parents. Besides, other barriers of failure in schools and low standard of achievement are due to the lack of proper assessment; counseling and guidance are not offered to students and parents before and during the tenure of their education. Similarly, the high rate of dropout after being enrolled is due to improper use of teaching learning strategies as well as other educational provisions. Even, examination or evaluation system is not suitable for these students. Lack of support systems like; IEP (Individual Education Plan) or provision of extra sessions to cope with the mainstream curriculum is remarkable (Choudhuri et al., 2005). Besides, lack of proper assessments of a student’s intellectual capability also plays a significant role in classroom performance as well as to hold on to the retention of students to avail school completion certificates. As a result, the necessity to standardize an appropriate and up to date assessment scale has become essential to mitigate the problem of disability prevalence and the present status of quality education for students with special needs and other marginalized population.

The Objectives of the Study

The study aimed to standardize the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (Fifth Edition, 2003) in Bangla for use in Bangladesh. However, the specific objectives, as a part of standardization process are stated as follows:

- To translate and adapt the ten subtests of Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale for children aged 6 to 16 years.

- To determine the reliability and validity of the adapted versions.

- To develop the norm for Bangladeshi children aged 6 to 16 years.

Following the description and importance of assessing the intellectual ability of an individual in this chapter, chapter two will discuss the literature review compiling the historical studies on intelligence and its assessment along with international and national perspectives on standardization of SB5. Besides, chapter three will describe the methods and methodology involved in standardizing the test. Whereas, chapter four will analyze the results found for the study in Bangladesh. Moreover, chapter five will explain the rationale and justification of the research. Finally, the conclusion and implication and further recommendations for the study will be discussed in chapter six followed by the limitations of the study in the field.

Literature Review

The chapter focuses on the review of psychometric tests, historical studies on intelligence, its assessment and historical perspectives on intelligence test development, history of the Stanford-Binet and its various editions. This chapter also covers the overview of international and national perspectives on standardization of Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, description of standardization process and cross cultural assessment. Moreover, this literature review is an approach to enter into the related field of knowledge and offers an opportunity to enhance the understanding for the accomplishment of a quality study.

Prior to the contributions of many theoretical and practicing psychologists in the early nineteen hundreds, the concept of intelligence as it is understood worldwide today was unknown. Thus, the change in focus began unfolding. From its initial pre-scientific and philosophical roots, the study of intelligence changed drastically (Meloff, 1987).

Review of Psychometric Tests

By the end of the 19th century, people attending scientific or industrial expositions were taking various tests that assessed their sensory and motor skills, the result of which were compared against norms (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). One active area in the scientific research is the tests of psychological characteristics most commonly, intelligence themselves. Intelligence and the ability to assess it, is considered as an important concept in relation to academic settings. Although many claim that intelligence is defined by what intelligence tests measure, many other theorists and researchers argue that this definition is too circular and narrow. Moreover, scores on intelligence tests are designed to reflect the definitions of intelligence rather than serve as an exact and unqualified representation of intellectual ability (Gardner, Kornhaber & Wake, 1996). Nevertheless, IQ tests are useful tools for various purposes. Moreover, psychometrics is applied widely in educational assessment to measure abilities in domains such as reading, writing, and mathematics. The main approaches in applying tests in these domains have been Classical Test Theory and the more modern Item Response Theory (IRT) and Rasch measurement models (Kline, 1999). Such approaches provide powerful information regarding the nature of developmental growth within various domains.

Besides, college entrance exams, classroom tests, structured interviews, assessment centers, and driving tests are also psychological tests. On the other ways, many popular psychological testing reference books also classify tests by subject. For example, the Seventeenth Mental Measurements Yearbook (Geisinger, Spies, Carlson, & Plake, 2007) classifies thousands of tests into 19 major subject categories like as Achievement, Behavior assessment, Developmental, Education, English, Fine arts, Foreign languages, Intelligence, Mathematics, Miscellaneous (for example, courtship and marriage, driving and safety education, etiquette), Multiaptitude batteries, Personality, Neuropsychological, Reading, Science, Sensor motor (Thompson, 2003). Although some are more typical, all meet the definition of a psychological test. Together, they convey the very different purposes of psychological tests. In the following figure, a continuum of some of the most and least commonly recognized types of psychological tests are shown (Chun, Cobb, & French, 1975).

Historical Studies on Intelligence and Its Assessment

During the era of psychometrics, intelligence was thought to be a single, inherit entity. The human mind was believed by some to be a “blank slate” that could be educated and trained to learn anything if taught in the appropriate manner (Sternberg, 2000). However, contrary to this notion, an increasing number of researchers and psychologists now believe that the opposite is true; that is, individuals are born with and possess different levels of ability. The development and use of intelligence tests have been one way that researchers and psychologists have attempted to support their argument. While intelligence is one of the most talked about subjects within psychology, there is no standard definition of what exactly constitutes ‘intelligence.’ Some researchers have suggested that intelligence is a single, general ability; while other believe that intelligence encompasses a range of aptitudes, skills and talents (Horn & Noll, 1994). The following are some of the major theories of intelligence that have emerged during the last 100 years.

Charles Spearman – General Intelligence.

British psychologist Spearman (1904) described a concept and referred to a general intelligence, or the g factor. After using a technique known as factor analysis to examine a number of mental aptitude tests, Spearman explained that scores on these tests were remarkably similar. People who performed well on one cognitive test tended to perform well on other tests, while those who scored badly on one test tended to score badly on others. He concluded that intelligence is general cognitive ability that could be measured and numerically expressed.

Louis L. Thurstone – Primary Mental Abilities.

Psychologist Thurstone (1938) offered a differing theory of intelligence. Instead of viewing intelligence as a single, general ability, Thurstone’s theory focused on seven different “primary mental abilities.” The abilities that he described were: verbal comprehension, reasoning, perceptual speed, numerical ability, word fluency, associative memory, spatial visualization.

Howard Gardner – Multiple Intelligences.

One of the more recent ideas to emerge is Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Instead of focusing on the analysis of test scores, Gardner proposed that numerical expressions of human intelligence are not a full and accurate depiction of people’s abilities. His theory describes eight distinct intelligences that are based on skills and abilities that are valued within different cultures. The eight intelligences Gardner described are: Visual-spatial Intelligence, Verbal-linguistic Intelligence, Bodily-kinesthetic Intelligence, Logical-mathematical Intelligence, Interpersonal Intelligence, Musical Intelligence, Intra personal Intelligence, Naturalistic Intelligence(Gardner, 1983).

Robert Sternberg – Triarchic Theory of Intelligence.

Psychologist Robert Sternberg defined intelligence as “mental activity directed toward purposive adaptation to, selection and shaping of, real-world environments relevant to one’s life.” While he agreed with Gardner that intelligence is much broader than a single, general ability, he instead suggested some of Gardner’s intelligences are better viewed as individual talents. Sternberg proposed what he refers to as ‘successful intelligence,’ which is comprised of three different factors (Sternberg, 1985).

On the other hand, human being has been fascinated by the noticeable differences in mental capacity that has existed among individuals in society. Ideas relating to intelligence remained a philosophical issue until the late nineteenth century when psychologists began the systematic investigation of intelligence (Thompson, 1984). In 1996, Williams reviewed the definition of intelligence in his studies that most experts would accept the constructs of goal directed behaviors’ that are adaptable across environments. He included in his studies the opinions of experts to define intelligence in two themes that are common to both definitions. The first common theme was focused on the individual learning from experience and the second on the individual’s ability to adapt to the environment. In several and similar studies, Chen, 2007; Hale & Jansen, 1994; Myerson, 2003, viewed the processing speed and working memory capacity as the currently predominant integrative constructs for explaining g. Much of the difficulty in developing an adequate intelligence assessment tool is the lack of a consensus definition of what the concept actually represents. Before selecting the task of assessing cognitive abilities, those abilities must be operationally defined. François (1995) stated that in order to make use of what intelligence tests explain us; we must first understand what intelligence is. Through the years, the nature of the types of abilities believed to represent intelligence has taken numerous routes. Even the term intelligence itself has recently taken a back seat to a broader viewpoint involving various cognitive abilities.

Spearman, in 1904, put forth the concept of a ‘g’ factor, or an overall general intelligence, based on the positive correlations between cognitive tests (Duncan, Seitz, Kolodny, Bor, Herzog, Ahmed, Newell, & Emslie, 2000). He used a factor analysis of many cognitive measures in order to suggest that the main underlying component of these measures was an overall intelligence, or ‘g’ (Spearman, 1904; Duncan et al., 2000).

In 2002, a study by Ken Richardson on “What IQ Tests Test” describes about how human intelligence should be and whether IQ tests actually measure it and if they don’t, what they actually do measure. The study suggests that IQ scores can be described in terms of sociocognitive-affective factors that differentially prepare individuals for the cognitive, affective and performance demands of the test. The paper shows that how such factors can explain the correlational evidence usually thought to validate IQ tests, including associations with educational attainments, occupational performance and elementary cognitive tasks, as well as the inter-correlation among tests themselves.

Studies on Intelligence Test Development

The study of intelligence and its measurement traces its roots to physicians, educators and psychologists who were deeply involved with population at the extremes of intellectual continuum. Esquirol (1938) and Seguin (1907) were committed to the study of intellectually disabled individuals, and Galton (1884) was fascinated by the mental abilities of geniuses. The separate contributions of these pioneers have been profoundly felt in the field of intelligence testing. It was the innovative research investigations of Binet (1903) who focused on the mental abilities of typical or average children at each age, that have had the longest, lasting and most direct effect on individual intelligence testing as we know it today (Anastasi, 1992).

Esquirol made several important contributions, most notably by distinguishing “between the idiots, whose intelligence does not develop beyond a very low level and the demented person” (Peterson, 1925). This distinction between intellectually disabled and emotional disturbance reflected a vital breakthrough for assessment and indicated the primitive state of the art in the early nineteenth century. Esquirol also described a hierarchy of retardation (or feeble mindedness, as it was known in earlier times) with ‘idiots’ occupying the bottom rung, followed by “imbeciles” and peaking with “morons” (Peterson, 1925). He was well ahead of his time in concluding that the use of language was the most dependable criterion for inferring a retarded individual’s intelligence level. Esquirol (1938) was also credited with developing a precursor of the mental age concept by pointing out that an idiot is incapable of acquiring the knowledge common to other persons of his own age (Anastasi, 1976). Seguin was heavily influenced in his work with mentally retarded individuals by Itard, of Wild Boy of Aveyron fame. Like Esquirol, Seguin (1907) tried to establish criteria for distinguishing between different levels of retardation, although he focused on sensory discrimination and motor control. Optimism regarding treatment of retarded individuals characterized Seguin’s approach and he instituted a comprehensive programme of sense training and muscle training techniques much of which live on in present day institutions for the mentally retarded (Anastasi, 1992: 1976).

Francis Galton (1884) transformed his enthusiasm for gifted men and genius and the study of the genetics of intelligence into the development of what was apparently the first comprehensive individual intelligence test. Galton believed that intelligence must be intimately related to sensory abilities because environmental knowledge comes to us via the senses, he developed a series of tests such as weight discrimination, reaction time, visual discrimination, steadiness of hand,keenness of sight and strength of squeeze. His empirical justification for this test battery came from comparisons between gifted and retarded individuals that, not surprisingly, showed obvious superiority in favour of the gifted (Peterson, 1925). Galton’s influence spread far beyond his laboratory as “Galton type tests” were developed throughout Europe and the United States. Cattell (1890) coined the term “mental tests”; Galton’s influence was clearly evident in Cattel1’s 40-60 minute individual examination, as after-images, colour vision, sensitivity to pain and the like (Peterson, 1925). Cattell elaborated on and improved his mentor’s methodology by emphasizing the vital notion that administration procedures must be standardized to obtain results that were strictly comparable from person to person and from time to time (Huq, 1992).

Later a challenge was issued to the Galton view of sensory and motor intelligence from Alfred Binet of France. In collaboration with Simon and Henri (1895), Binet conducted numerous investigations of complex mental tasks rejecting the Galton notion that performance on simple, elementary sensory discrimination and motor co-ordination tasks equates to intelligent behavior. According to Cattell (1976) and Horn & Noll (1997), Stella Sharp (1899) directly compared sensory-discrimination tests with tests of complex mental functions and concluded that the simplest mental processes yielded comparatively unimportant information, whereas the tests of Binet and Henri showed much value in assessing “individual psychical differences”. Even though initial reaction to the two studies was predominantly antitesting causing a lack of enthusiasm for the Galton-Cattell as well as the Binet-Henri approach in the United States, the methodology of Binet eventually triumphed first throughout Europe and finally in America (Peterson, 1925).

Interestingly, a research by Jensen (1979) and his students Vernon (1981) has revived the early work of Galton to some extent. Although they confirmed that simple reaction time measures contribute little to variation in intellectual function, these researchers have found substantial relationship between intelligence and complex reaction time over repeated trials of the same task. Thus adaptations of Galton’s work might yet be found to impact on objective intellectual assessment in future (Huq, 1992).

History of the Stanford-Binet and Its Various Editions

The most revolutionary contribution of all the theorists of their time was that of Alfred Binet and his young associate Theodore Simon. In 1905, they developed a useful tool to assess general intelligence, which is widely cited as the first major break- through in intelligence testing (Roid, 2003).

Early Work of Binet.

As a member of a French governmental commission working on mental retardation, Binet developed a practical test, sensitive to different levels of cognitive development, which could be given during a clinical interview. Alfred Binet’s early work began with intelligence testing, when Binet collaborated with Victor Henri to outline a project for the development of a series of mental tasks to measure individual differences (Binet & Henri, 1895).The tasks were designed to differentiate a number of complex mental faculties, including memory, imagery, imagination, attention, comprehension, aesthetic sentiment, moral sentiment, muscular strength, motor ability and hand-eye coordination.

The 1905 Binet – Simon Scale in France.

Binet initiated the leading role in devising a useful and reliable diagnostic system for identifying children with mental retardation. Binet’s project culminated in the publication of the first practical intelligence test with physician Theodore Simon (Binet & Simon, 1905). Binet sought to make the 1905 scale efficient and practical: “We have aimed to make all our tests simple, rapid, convenient, precise, heterogeneous, holding the subject in continued contact with the experimenter, and bearing principally upon the faculty of judgment” ( Binet & Simon, 1916).The scale consisted of 30 items, which were scored on a pass-fail basis. The items presented various word problems, paper-cutting tasks, repeating sentences and digits, and comparing blocks to put them in order by weight (Wolf, 1973).

The 1905 scale included several important innovations that would be used in subsequent measures of intelligence. Items were ranked in order of difficulty and accompanied by careful instructions for administration. Binet and Simon also utilized the concept of age-graded norms (Wolf, 1973).The use of age-graded items allowed the scale to estimate mental age by the pattern of correct answers. The 1905 Binet – Simon Scale was revised in 1908 (Binet & Simon, 1908) and again in 1911. By the completion of the 1911 edition, Binet had extended the scales through adulthood and balanced them with five items at each age level. The scales included procedures for assessing language, auditory and visual processing, learning, memory, judgment and problem solving (Roid, 2003).

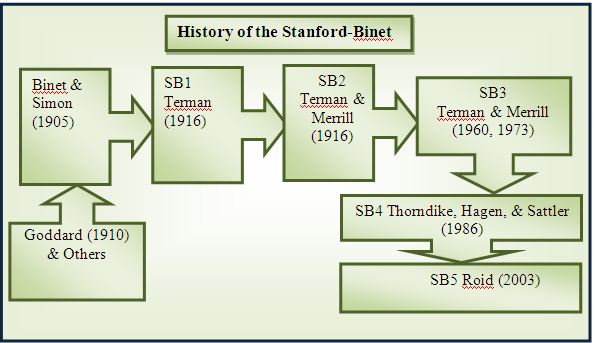

Figure 1. History of the Stanford-Binet.

Terman’s 1916 Stanford Revision in America.

Realizing the importance of the theoretical and practical value of Binet’s work, Terman (1911) of Stanford University began to adapt the test to the American culture. Within a few years, the improved scale was published as the Stanford Revision and Extension of the Binet-Simon Scale. However, Terman’s 1916 revision retained Binet’s concept of intelligence as a complex mixture of abilities and is the only revision that has stood for publication to the present day. The standardization that Terman accomplished was quite rigorous for the early 1900s and increased the scale’s technical quality (Roid, 2003).

Revisions of the Terman Scales in 1937, 1960 and 1972.

Within 20 years of its release in 1916, the Stanford revision emerged as the most widely used test of intellectual ability in America. The scale had several language translations and was used internationally. In subsequent years, Terman continue to experiment with easier and more difficult items to extend the measurement scale downward and upward and to increase the age range by including more standardization samples. The new edition was called the New Revised Stanford-Binet Tests of Intelligence (Terman & Merrill, 1937).

The 1937 revision was standardized on 3,200 examinees aged 1 year 6 months to 18 years. Terman made efforts to include a broader representation of geographic regions and socioeconomic levels in the normative sample. Two alternative forms, Form L and Form M were included. Improvements over the 1916 edition included greater coverage of nonverbal abilities, less emphasis on recall memory, extended range of the scale at the lower and upper ends, and more objectified scoring methods. (Terman & Merrill, 1937). As happens with any widely used test of ability or achievement, obsolete items were considered for further revision by Terman and Merrill based on the accumulated information and data collected since 1937. Thus, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, Third Revision, 1960 was published. Several new features were included in the third revision as the use of deviation IQ, (standardized normative mean of 100 and SD of 16), combination of Form L-M while keeping the most discriminating 142 items from the 1937 revision.

After Maud Merrill retired, Robert L. Thorndike of Columbia University was asked to lead a project to collect new norms for the third edition. Thus, the same edition was reprinted with the new normative tables-an update of Form L-M (Terman & Merrill, 1973). Because the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT; Thorndike & Hagen, 1994) was being standardized at the same time as the 1972 reforming of the Stanford-Binet, Thorndike selected subjects and some siblings of subjects tested on the CogAT to compose the new norm sample. The stratification variables used on the sample (e.g., age, geographic region, ethnicity, and community size) was similar to those used today, as were the levels of ability on the verbal portion of the CogAT. The items in the test remained essentially the same as on the 1960 revision, with two minor exceptions.

The 1986 Edition by Thorndike, Hagen and Sattler.

In 1986 Thorndike and his associates accomplished the test with a new appearance and structure. The Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale Fourth Edition (SB4) was based on a four-factor, hierarchical model with general ability (g) on a bell curve score (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986). The four cognitive factors were Verbal Reasoning, Abstract/ Visual Reasoning, Quantitative Reasoning and Short-Term Memory. The most significant change from previous editions, however, was the use of point scales for all subtests rather than the developmental age levels used in previous forms. Vocabulary was still retained as a routing test, allowing the test to be tailored to the examinee’s verbal ability. Also, many classic Stanford-Binet tasks were retained, including absurdities, vocabulary, matrices, quantitative reasoning and memory for sentences—tasks also included in the SB5. Composite and profile scores for each subtest would permit a comprehensive examination of strengths and weaknesses among abilities within general intelligence (Roid, 2003).

Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale Fifth Edition (SB5) by Gale H. Roid.

Development of the SB5 is heavily based on the new Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory of intellectual abilities. In continuation with the past editions as the SB4, five key factors of CHC theory were selected for the development of SB5. In 1995, Gale H. Roid, the author of the SB5 had undertaken the initiative for a new revision and developed it as the fifth edition in 2003. Considering a normative sample of 4,800 subjects, whose ages ranged from 2 to 85 years. The Fifth Edition includes extensive high-end items designed to measure the highest level of gifted performance. It also includes improved low-end items for better measurement and low-functioning of young children with intellectual disability. Furthermore, the inclusion of age-graded norms in SB5 serves as a unique criterion provided for the estimation of mental age (Roid, 2003a; Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986).

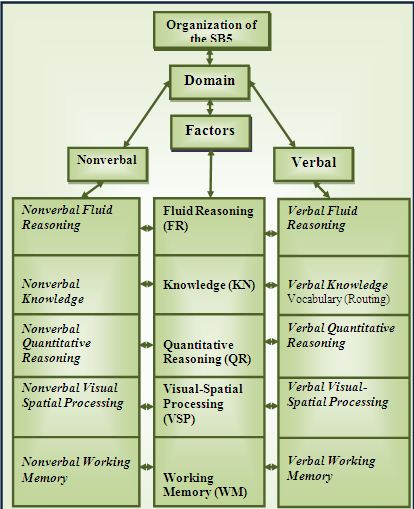

Composition of the SB5.

The SB5 design crosses the five factors with the two domains resulting in ten (5×2) subtests. Based on the literature such as manuals of SB5 by Roid (2003), the factors, domains and subtests are reviewed below.

Factors.

Factors are the important dimensions of cognitive ability that are measured by the items and subtests of SB5. The factors measured in the SB5 are: Fluid Reasoning (FR), Knowledge (KN), Quantitative Reasoning (QR), Visual-Spatial Processing (VSP) and Working Memory (WM). These factors, the central components of SB5, are discussed below.

Fluid Reasoning (FR)

Fluid Reasoning, as defined by Roid, (2003b) is “the ability to solve verbal and nonverbal problems using inductive or deductive reasoning.” The inductive reasoning component requires the individual to derive the general whole from its specific parts. Likewise, the deductive reasoning component requires that the individual draw a conclusion, implication, or specific example from a general piece of information about the topic.

Knowledge (KN)

According to Roid (2003b), knowledge “is a person’s accumulated fund of general information acquire at home, school, or work.” This construct is often referred to as crystallized intelligence, as it involves learned material that has been stored in long term memory. It also requires perception of detail, attention, concentration, geography, science, and inference skills.

Quantitative Reasoning (QR)

Roid (2003b) defines Quantitative Reasoning, as “an individual’s facility with numbers and numerical problem solving, whether with word problems or with pictured relationships” (p. 136). The items included on the SB5 Quantitative Reasoning target problem solving abilities as opposed to rote mathematical knowledge. As the subtests progress, items become more complex.

Visual-Spatial Processing (VSP)

Visual-Spatial Processing, as defined as the “measures an individual’s ability to see patterns, relationships, spatial orientations, or the gestalt whole among diverse pieces of a visual display” (p. 137). The items of this factor assess the individual’s ability to move pieces and shapes to form a proper whole. All levels within this area address visual construction abilities (Roid, 2003b).

Working Memory (WM)

In 2003, Roid defines Working Memory, as “a class of memory processes in which diverse information stored in short-term memory is inspected, sorted, or transformed” (p. 137). The individual must filter out the irrelevant information and maintain focus on the pertinent. Furthermore, the information must be manipulated, which places both memory, organizational, and visual-spatial demands on the individual.

Domains.

A domain represents the degree to which a class of item requires the use of language skills, particularly in generating a response to an item. The SB5 contains two domain composites: Nonverbal and Verbal domains. The assessors should consider that the terms “nonverbal “and “verbal” are relative and comparative terms in the SB5. At present, the two domains are discussed accordingly.

Nonverbal Domain

This domain requires less language ability or little or no vocal response or speech and thus has lower language demands. The nonverbal tasks involve a small degree of examiner-spoken directions.

Verbal Domain

This domain requires some degree of expressive language, often as simple as a word or phrase or a degree of reading for the average and high functioning students.

Consideration of the nonverbal versus verbal difference, verbal domain has become increasingly important as society has become more culturally and linguistically diverse.

Nonverbal Fluid Reasoning (NFR)

The Fluid Reasoning subtests within the nonverbal domain are Object-Series and Matrices. Initially, the individual is required to match objects. These objects are then placed into a series, either repetitive or not, that the individual must complete. The last phase is similar to the classic matrix-reasoning measures that are common among intelligence testing. (Roid, 2003b).

Nonverbal Knowledge (NK)

The Knowledge subtests within the nonverbal domain include procedural knowledge and picture absurdities. At the lowest end of the spectrum, the subject is required to communicate basic human needs using gesture. As the task demands increase, the subject is presented with impossible pictures in which he is required to point out what is odd or impossible about the scene. The Nonverbal Knowledge tasks tax an individual’s basic level of common knowledge about natural phenomena (Roid, 2003b).

Nonverbal Quantitative Reasoning (NQR)

The Quantitative Reasoning subtests within the nonverbal domain have been carried over from the SB4. However, the focus of the subtests from the SB5 is on the reasoning behind the mathematical concepts, as opposed to the rote solving of mathematical items. In order to succeed on the higher level tasks, the subject must use problem solving strategies, persistence, and cognitive flexibility (Roid, 2003b).

Nonverbal Visual Spatial Processing (NVSP)

The Visual-Spatial Processing subtests within the nonverbal domain incorporate the form board activity from the SB4. However, tasks have been added in order to expand the evaluation of Nonverbal Visual-Spatial Processing activities. Initially, shapes are matched and then inserted into forms. As the individual progresses, accurate duplication of patterns using the provided shapes is targeted (Roid, 2003b).

Nonverbal Working Memory (NWM)

The Working Memory subtests within the nonverbal domain begin by assessing the individual’s ability to hold fundamental, observable objects in short term memory and progress into a rote memory block tapping task. However, towards the higher end of the subtests, the information presented becomes less concrete and more complex (Roid, 2003b).

Verbal Fluid Reasoning (VFR)

The Fluid Reasoning subtests within the verbal domain measures reasoning, absurdities and analogies. As mentioned earlier, the individual is required to sort, identify what is absurd or impossible about verbally presented sentences and pictures, to make generalizations about the information provided (Roid, 2003b).

Verbal Knowledge (VK)

The Knowledge subtests within the verbal domain are Vocabulary. The subject is required to identify several objects and perform through picture vocabulary. As the difficulty level increases, the subject must clearly define vocabulary words. At the upper levels, performance on this subtest is influenced by schooling (Roid, 2003b).

Verbal Quantitative Reasoning (VQR)

The Quantitative Reasoning subtests within this verbal domain measure an individual’s ability to use a variety of mathematical skills. The subtest assesses the individual’s basic addition and subtraction skills, geometric, measurement skills and to complete word problems involving multiplication at difficulty level (Roid, 2003b).

Verbal Visual Spatial Processing (VVSP)

The Visual-Spatial Processing subtests within the verbal domain assess the individual’s ability to understand spatial concepts and relationships. The lower levels of the test include terms such as “ahead” and “behind,” and do not rely heavily upon expressive vocabulary. However, as the task demands increase, expressive vocabulary is needed to explain the complex relationships between geographic information (Roid, 2003b).

Figure 2. Organization of the SB5.

Verbal Working Memory (VWM)

The Working Memory testlets within the verbal domain begin with Memory for Sentences, which has long been a component of the Binet scales. As the subtests increase in difficulty, the individual is required not only to retain bits of information in working memory, but to manipulate these bits as well. Oftentimes, individuals are able to complete the rote memory sections but encounter difficulty when information manipulation is required (Roid, 2003b).

Based on extensive discussion of SB5, the above mentioned subtests are basic key to judge an individual’s overall intellectual ability through an intelligence scale as SB5. Thus, the author has given an emphasis on these subtests as major variables for her study as standardization of the SB5 for use in Bangladesh.

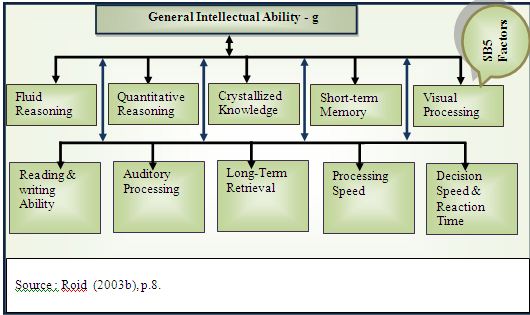

Changes from the Previous Editions.

The Stanford-Binet has a long tradition, beginning with Terman’s 1916 American revision called the Stanford Revision and Extension of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale (Binet & Simon, 1908).Through various editions in 1937, 1960, and 1986, the Stanford-Binet has become widely known as a standard measure of intellectual abilities. The SB5 blends the use of routing subtests in the point-scale format of the 1986 edition with the functional level design of the 1916 to 1960 editions (Roid, 2003). Moreover, modern Item Response Theory (IRT) provides a strong psychometric foundation for the routing subtest and functional-levels design (Rasch, 1980; Wright & Uneacre, 1999). Test design for the SB5 employed many of the “new rules of measurement,” based on IRT, recognized by psychometric experts (Embretson, 1996; Embretson & Hershberger, 1999; Reckase, 1996). These new measurement rules include methods such as calibrating items in an extensive item pool and adaptive testing through the use of routing subtests. By adapting the test, the routing procedure of the SB5 increases the precision of measurement by tailoring the level of item difficulty to the examinee’s level of cognitive functioning. Traditionally, routing has been a unique feature of the Stanford-Binet scales. Many of the familiar subtests of previous editions remain in the SB5. Examples include Picture Absurdities, Matrices, Vocabulary, and Memory for Sentences, Quantitative Reasoning, and Verbal Absurdities. The use of a hierarchical model of intelligence (with a global g factor and multiple factors at a second level in Fig 3), established in the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition (SB4) (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986) is repeated in the SB5. A few classic items, such as those in picture absurdity, have been included in the new edition to provide consistency across editions. Changes from the Fourth Edition include a general modernization of artwork and item content as well as the following enhancements (Roid, 2003).

Additional factor.

The SB5 includes five factors (Fluid Reasoning, Knowledge, Quantitative Reasoning, Visual-Spatial Processing, and Working Memory) instead of the four factors in the SB 4.

Child-friendly materials.

Responding to many user requests, the SB5 brings back many of the toys and colorful manipulative that are engaging for small children and helpful for early-childhood assessment.

Enhanced nonverbal content.

One half of the subtests in the new edition employ a nonverbal mode of testing, requiring no, or minimal, verbal responses from the examinee. Unique to the SB5, compared to other intelligence batteries, is that the Nonverbal IQ covers all five major cognitive factors.

Increased Breadth of the Scale.

New items to measure very low functioning and very high giftedness have extended the scales upward and downward to provide a wider range of assessment. For example, Object Series items were added to the lower end of Matrices to provide an exceptional floor for the routing tests.

Enhanced usefulness of the test.

The types of items, scores, and factors for the SB5 have been designed to facilitate clinical use of the SB5. The contrasts between verbal and nonverbal facets of each of the five factors, the Abbreviated and Nonverbal forms of the test, and the Working Memory subtests enhance the interpretations and applications of the test in clinical, school, and occupational settings. Based on the description of changes from earlier editions, the unique features of the SB5 are as follows (Maddox, 2003):

- Wide variety of items requiring nonverbal performance by examinee – ideal for assessing subjects with deafness or communication disorders.

- Ability to compare verbal and nonverbal performance – useful in evaluating learning disabilities.

- Greater diagnostic and clinical relevance of tasks, such as verbal and nonverbal assessment of working memory.

- Extensive high-end items, many adapted from previous Stanford-Binet editions and designed to measure the highest level of gifted performance.

- Improved low-end items for better measurement of young children, low functioning older children or adults with intellectual disability.

- Co-normed with measures of visual-motor perception and test-taking behavior.

- Enhanced artwork and manipulative that are both colorful and child-friendly.

The Standardization of (Original) 2003 Edition (SB5)

The total of ten subtests, five nonverbal and five verbal provides measures of the five CHC factors in the SB5: Fluid Reasoning, Knowledge, Quantitative Reasoning, Visual-Spatial Processing and Working Memory. Out of nearly 1000 items from the pilot and tryout phases of the project, approximately 375 items were employed in the 5th standardization edition. The final published version separated the nonverbal and verbal subtests into separate easel books whereas the longer Standardization Edition had a mixture of nonverbal and verbal subtests in each functional level of the test. Very close statistical equivalence for the two versions (longer Standardization Edition and shorter final version) was demonstrated, and no significant context or order effects were observed between the two versions (Roid, 2003).

Psychometric Properties of (Original) SB5 for Standardization

Extensive studies of reliability, validity, and fairness were conducted as part of the SB5 standardization.

Item Analysis.

The items from all Stanford-Binet editions were rated by experts in the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory of intellectual abilities during the first year of the development of the SB5(Carroll, 1993; Cattell, 1963; Evans, Floyd, McGrew, & Leforgee, 2001; Horn, 1994). The experts noted the CHC factor or factors being measured by each item, and all items were classified into comprehensive lists for each factor. These lists proved valuable in creating early versions of new items and new subtests. Factor analyses of Forms L and M of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (Terman & Merrill, 1937) and the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition (Thorndike et al., 1986) further verified the items and subtests most central to each of the factors. Extensive item analyses, including classical and item response theory methods, were conducted on SB5 items. Item analyses, subtest scaling analyses, reliability studies, and item factor analyses were conducted using pilot, tryout edition, and standardization edition studies. The final selection of items for the standardization edition involved many sources of information, item analyses, and the comparative merit of items.

Norm.

The sample was nationally representative and matched to percentages of the stratification variables identified in U.S. Census Bureau (2001) publications. The stratification variables were age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region and socioeconomic level, each of which is being defined below.

Age.

For stratified sampling purposes, 30 age groups were defined. Age was defined by subtracting the birth date from the testing date, with months of age treated as 30 days.

Sex.