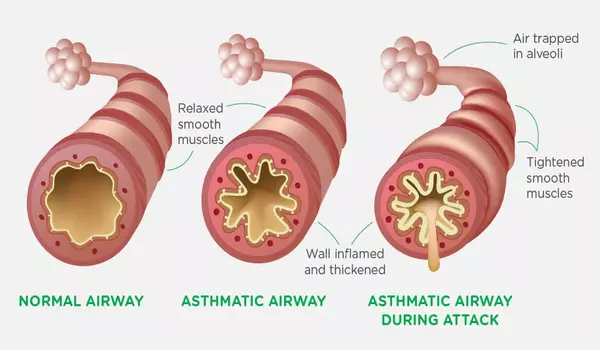

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease marked by airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. T cells are white blood cells that play an important function in the immune system. While asthma can be triggered by a variety of reasons such as allergies, infections, and environmental irritants, the involvement of T cells in asthma is still being studied.

Researchers from the University of Southampton and the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) in California have discovered a subset of immune cells that may be responsible for severe asthma. These cells appear to inflict the most harm in males who acquire asthma later in life when they congregate in the lungs.

“If you’re a man and develop asthma after the age of 40, there’s a good chance that this T cell population is in your lungs,” says LJI Research Assistant Professor Gregory Seumois, who co-led the study with LJI Professor Pandurangan Vijayanand.

According to the current study, published in MED, asthma patients who have these cells in their lungs are more prone to experience difficult-to-treat, perhaps lethal, asthma attacks. Normally, a doctor would prescribe a general therapy to suppress an asthmatic’s immune reaction, but these cells do not respond to treatment.

We have to think of severe asthma as having different subtypes, and treatment has to be tailored according to these subtypes because one size does not fit all. The researchers intend to use sequencing methods and other techniques to find more biomarkers and asthma patient subgroups.

Professor Hasan

These T cells, known as ‘cytotoxic CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells,’ were discovered by the investigators owing to volunteers in the NHS clinic-based WATCH project. It follows hundreds of asthma patients of all ages, genders, and illness severity levels. Researchers are discovering new links between asthma symptoms and immune cell activity by tracking patients for several years and analyzing their immune cell populations.

“Once you understand the role of cells like these T cells better, you can start developing treatments that target those cells,” says WATCH project director Dr. Ramesh Kurukulaaratchy, Associate Professor at the University of Southampton and researcher at the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre.

Scientists now hope to learn more about these cells and their role in asthma development in order to develop personalised therapies for asthma patients.

How harmful T cells drive asthma

T cells are referred to as “memory” cells because they respond to substances that the body has previously fought. They aid in the body’s defense against viruses and germs, but the same T cell memory is a major issue for asthma patients. Their misled T cells mistake innocuous chemicals like pollen for harmful inflammatory responses.

Men who got asthma later in life had an abundance of these potentially dangerous T cells. Their lungs should have housed a varied range of CD4+ T cell types, but more than 65 percent of the cells in this group were cytotoxic CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells.

Personalized asthma treatments

LJI scientists’ single-cell RNA sequencing gives a ‘biomarker’ to help detect cytotoxic CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells in more patients in the future.

According to Dr. Kurukulaaratchy, the discovery of this biomarker implies a “paradigm shift” in asthma research. Previously, scientists and clinicians classified asthma patients into two categories: ‘T2 high’ and ‘T2 low’. The research team demonstrated the value of drilling down to uncover many additional asthma patient subgroups in a study published earlier this year; their analysis revealed that 93% of WATCH patients with severe asthma were in the T2 high category.

Professor Hasan Arshad, co-author of the study and Chair in Allergy and Clinical Immunology at the University of Southampton, researcher at the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, and Director of The David Hide Asthma and Allergy Research Centre on the Isle of Wight, says, “We have to think of severe asthma as having different subtypes, and treatment has to be tailored according to these subtypes because one size does not fit all.”

The researchers intend to use sequencing methods and other techniques to find more biomarkers and asthma patient subgroups.