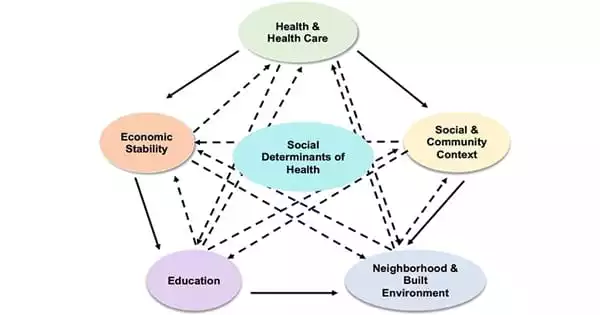

Individuals’ personal circumstances that affect their health and well-being are referred to as social determinants of health. They include political, social, and cultural issues, as well as the ease with which someone can obtain healthcare, education, a safe place to live, and healthy food. The social determinants of health are a diverse set of factors that present in all parts of society. They are, however, distinct from medical care or a person’s personal lifestyle choices.

The economic and social variables that influence individual and group disparities in health status are referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH). They are the health-promoting elements found in one’s living and working environment (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power) rather than individual risk factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence illness risk or vulnerability.

The social determinants of health (SDOH) are the factors in the contexts where individuals are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functional, and quality-of-life outcomes and hazards. Over the last two decades, the public health community’s attention has been attracted increasingly to the social determinants of health (SDH)—the elements other than medical treatment that can be impacted by social policies and shape health in profound ways. To prevent potential confusion between “health” and “health care,” we refer to clinical services as “medical care” rather than “health care.”

Public policies that represent the area’s dominant political ideology frequently impact the distributions of socioeconomic determinants. According to the World Health Organization, “this unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a ‘natural’ phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements [where the already well-off and healthy become even richer and the poor who are already more likely to be ill become even poorer], and bad politics.”

A vast and compelling body of research has accumulated, particularly in the last two decades, indicating that social factors, in addition to medical care, have a powerful influence in determining health across a wide range of health indicators, contexts, and populations. This data does not dispute that medical treatment influences health; rather, it suggests that medical care is not the main influence on health and that the effects of medical care may be more limited than usually assumed, especially in determining who becomes sick or injured in the first place.

However, the links between social variables and health are rarely straightforward, and there are ongoing debates about the quality of the evidence establishing a causal role for specific social factors. Meanwhile, researchers increasingly are calling into question the appropriateness of traditional criteria for assessing the evidence.

Particular attention is paid to the social determinants of health in poverty and the social determinants of obesity. SDOH contributes to widespread health disparities and inequities. People who do not have access to grocery stores that sell healthful foods, for example, are less likely to be healthy. This increases their risk of health problems including heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, and even lowers their life expectancy in comparison to persons who have access to healthful foods.