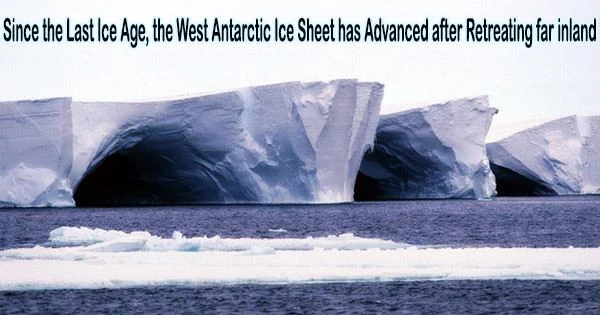

If global temperatures increase by 1.5 to 2.0 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit) over preindustrial levels in the coming decades, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may reach a threshold of irreversible retreat.

According to recent study, the grounded edge of the ice sheet may have been as much as 250 kilometers (160 miles) inland from where it is now 6,000 years ago. This suggests that the ice sheet withdrew deeply into the continent after the last ice age then advanced again before the current retreat started.

“In the last few thousand years before we started watching, ice in some parts of Antarctica retreated and re-advanced over a much larger area than we previously appreciated,” said Ryan Venturelli, a paleoglaciologist at Colorado School of Mines and lead author of the new study. “The ongoing retreat of Thwaites Glacier is much faster than we’ve ever seen before, but in the geologic record, we see the ice can recover.”

The work is published in AGU Advances, a journal that publishes open-access, high-impact research across the Earth and space sciences. It offers the first geologic restriction on the location and movement of the ice sheet since the previous ice age.

When we set out to sample this lake, we weren’t sure what we would find out about ice history, but the fact that deglaciation persisted this far inland was not that wild of a possibility. This area of West Antarctica is really flat. There is nothing to put brakes on the retreat of the grounding line. No real topographical doorstops.

Ryan Venturelli

The glacier or ice sheet’s grounding line is the point at which it starts to float as an ice shelf on water. From the West Antarctic Ice Sheet’s grounding line, the Ross Ice Shelf now stretches hundreds of kilometres out into the ocean. The leading edge of the ice is exposed to ocean water, which can induce a rapid melting zone at the grounding line.

“The concern of grounded ice loss is because the loss of ice on land is what contributes to sea level rise,” Venturelli said. “As grounding lines retreat farther inland, the more vulnerable the ice sheet becomes as it exposes thicker and thicker ice to the warming ocean.”

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet was so massive during the Last Glacial Maximum, some 20,000 years ago, that it was grounded on the ocean floor beyond the limit of the continent. The majority of prior data show a consistent retreat since then, which was sped up in the past century by human-caused climate change.

The question for Venturelli was just how far inland the ice sheet had retreated after the last ice age. Without understanding it, it is difficult to forecast the Antarctic Ice Sheet’s sensitivity to and response to future climate change.

The answer lay in a lake nearly twice the size of Manhattan that was cut off from the atmosphere of today by a kilometer (0.6 miles) of ice. To reach it, Venturelli and her team carefully melted their way in with a hot water “drill.” Once they had access, they pulled up samples of lake water and carbon-filled sediments from the lake bed. Using radiocarbon dating, they found the carbon was about 6,000 years old.

The discovery shows that what is now a lake was once the ocean floor as the radiocarbon (carbon-14) in these sediments must have come from seawater. This location is 150 kilometers (93 miles) from the present-day ice edge.

When the ice covered the lake, it preserved the carbon as a component of the sediments that make up the lake bottom. Additionally, the grounding line may have been 100 kilometers (62 miles) or even further inland at that time, according to radiocarbon in water taken from the same lake.

“When we set out to sample this lake, we weren’t sure what we would find out about ice history, but the fact that deglaciation persisted this far inland was not that wild of a possibility,” Venturelli said. “This area of West Antarctica is really flat. There is nothing to put brakes on the retreat of the grounding line. No real topographical doorstops.”

The new evidence of Antarctic ice’s ability to make a comeback was welcome news for Venturelli.

“It can be a bummer sometimes, studying ice loss in Antarctica,” Venturelli said. “Although the re-advance identified in the geologic record happens over thousands of years, I like to think of studying the process of reversibility as a little shred of hope.”

Assessing the circumstances that allowed the ice to re-advance is Venturelli and her co-authors’ next major challenge. One explanation is that the land was raised sufficiently by the rebound from the tremendous weight of the ice sheet to keep back the water and allow the ice to regenerate.

Another possibility is that the ice sheet switched from retreat to advance due to minute climatic changes. Any one of these factors could have been present in combination.