A new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, discovered that having shingles is associated with a 20% increased long-term risk of subjective cognitive loss. According to the researchers, the study’s findings add to the case for obtaining the shingles vaccine to reduce the risk of having shingles. Their findings were reported in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy.

“Our findings show long-term implications of shingles and highlight the importance of public health efforts to prevent and promote uptake of the shingles vaccine,” said corresponding author Sharon Curhan, MD, of the Channing Division for Network Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Given the growing number of Americans at risk for this painful and often disabling disease and the availability of a very effective vaccine, shingles vaccination could provide a valuable opportunity to reduce the burden of shingles and possibly reduce the burden of subsequent cognitive decline.”

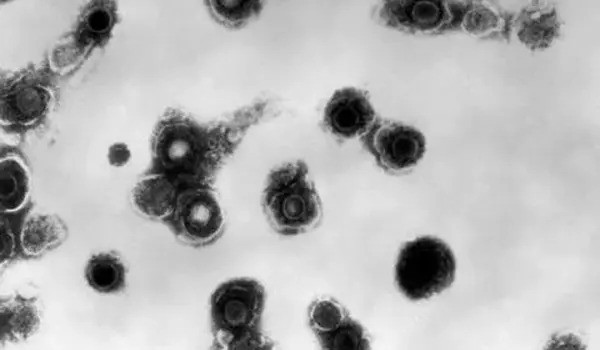

Shingles, often known as “herpes zoster,” is a viral infection that typically results in a painful rash. Shingles is caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), which also causes chickenpox. After a person contracts chickenpox, the virus remains in their body for the rest of their lives. Our immune system usually prevents the virus from infecting us. Years or even decades later, the virus might reactivate as shingles.

Our findings show long-term implications of shingles and highlight the importance of public health efforts to prevent and promote uptake of the shingles vaccine.

Sharon Curhan

Almost all people in the United States aged 50 and up have been infected with VZV and are thus at risk for shingles. There is a growing amount of evidence that herpes viruses, especially VZV, can cause cognitive deterioration. Subjective cognitive decline refers to an individual’s perception of greater or more frequent confusion or memory loss. It is a type of cognitive impairment and one of the first visible symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Previous investigations on shingles and dementia have produced mixed results. Some studies suggest that shingles increases the risk of dementia, whereas others show no association or a negative association. In recent trials, the shingles vaccine was linked to a lower incidence of dementia.

To learn more about the link between shingles and cognitive decline, Curhan and her team used data from three large, well-characterized studies of men and women over long periods: The Nurses’ Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study 2, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. The study included 149,327 participants who completed health status surveys every two years, including questions about shingles episodes and cognitive decline. They compared those who had shingles with those who didn’t.

Curhan designed the study with first author Tian-Shin Yeh, formerly of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. The researchers found that a history of shingles was significantly and independently associated with a higher risk — approximately 20 percent higher — of subjective cognitive decline in both women and men. That risk was higher among men who were carriers of the gene APOE4, which is linked to cognitive impairment and dementia. That same association wasn’t present in the women.

Researchers do not understand the processes that relate the virus to cognitive health, but there are various ways it could contribute to cognitive deterioration. There is accumulating evidence that VZV causes vascular illness, known as VZV vasculopathy, in which the virus damages blood arteries in the brain or body. Curhan’s group had previously discovered that shingles was linked to an increased long-term risk of stroke or heart disease.

Other processes that may explain how the virus causes cognitive impairment include inflammation in the brain, direct damage to nerve and brain cells, and activation of other herpesviruses.

This study’s shortcomings include the fact that it was an observational study, the information was relied on self-report, and the participants were largely white and highly educated. In future studies, the researchers hope to learn more about preventing shingles and its complications.

“We’re evaluating to see if we can identify risk factors that could be modified to help reduce people’s risk of developing shingles,” Curhan said. “We also want to study whether the shingles vaccine can help reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes from shingles, such as cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.”