Virus research should be conducted in controlled laboratory settings by trained professionals who adhere to strict safety guidelines. There are already protocols in place for studying and monitoring infectious diseases in order to avoid the unintentional release of dangerous pathogens or potential outbreaks.

Rather than waiting for the next outbreak, two virologists argue that the scientific community should invest in a four-part research framework to proactively identify animal viruses that may infect humans.

The majority of what scientists know about viruses in animals is the list of nucleotides that make up their genomic sequence, which, while useful, provides very few hints about a virus’s ability to infect humans. Rather than waiting for the next outbreak, two virologists argue in a SciencePerspective article that the scientific community should invest in a four-part research framework to proactively identify animal viruses that may infect humans.

“A lot of money has been invested in sequencing viruses in nature with the hope of predicting the next pandemic virus based solely on the sequence. And I believe that is a fallacy,” said Cody Warren, assistant professor of veterinary biosciences at The Ohio State University and co-lead author of the study.

We are continually going to be exposed to the viruses of animals. Things are never going to change if we stay on the same trajectory. And if we stay complacent and only study those animal viruses after they jump into humans, we’re constantly going to be working backwards.

Cody Warren

“Experimental studies of animal viruses are going to be invaluable,” he said. “By measuring properties in them that are consistent with human infection, we can better identify those viruses that pose the greatest risk for zoonosis and then study them further. I think that’s a realistic way of looking at things that should also be considered.”

Warren wrote the opinion piece with Sara Sawyer, a professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at the University of Colorado Boulder.

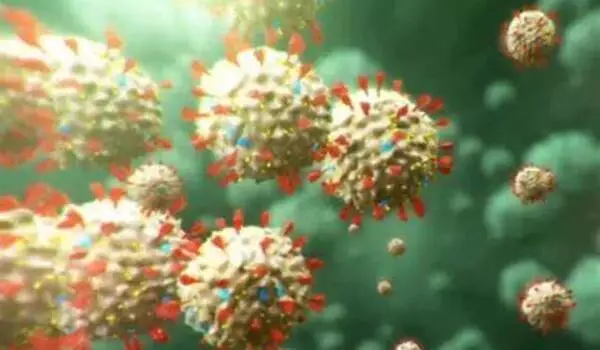

One key message Warren and Sawyer want to convey is that knowing an animal virus can attach to a human cell receptor does not provide a complete picture of its zoonotic potential. They propose a series of experiments to assess an animal virus’s ability to infect humans: Can it use human cells to replicate and multiply if it is discovered to enter human cells? Can viral particles survive human innate immunity after they are produced? And have human immune systems ever been exposed to another virus from the same family?

Answering these questions could allow scientists to put a pre-zoonotic candidate virus “on the shelf” for further study, such as developing a quick way to diagnose the virus in humans if an unrelated illness appears and testing existing antivirals as potential treatments, according to Warren.

“Where it becomes difficult is that there may be many animal viruses out there with signatures of human compatibility,” he explained. “So, which ones do you choose to prioritize for further research?” That is something that must be thoroughly considered.”

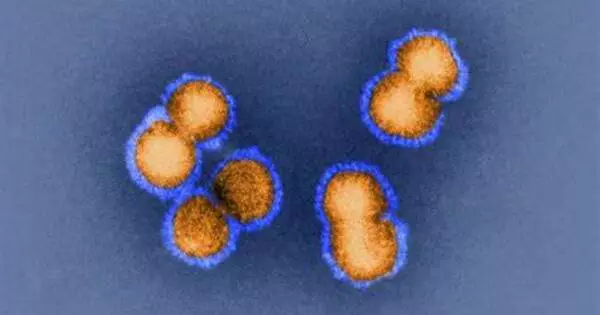

According to him and Sawyer, a good starting point would be to assume that viruses that pose the greatest risk to humans come from “repeat offender” viral families that are currently infecting mammals and birds. Coronaviruses, orthomyxoviruses (influenza), and filoviruses (which cause hemorrhagic diseases such as Ebola and Marburg) are among them. The Bombali virus, a new ebolavirus, was discovered in bats in Sierra Leone in 2018, but its ability to infect humans is unknown.

Then there are arteriviruses, like the simian hemorrhagic fever virus found in wild African monkeys, which Sawyer and Warren recently discovered has a good chance of spreading to humans because it can replicate in human cells and undermine immune cells’ ability to fight back.

The global lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in 2020 is still a fresh and painful memory, but Warren notes that the disastrous consequences of the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 could have been much worse. Only because scientists had spent decades studying coronaviruses and knew how to attack them was it possible to have vaccines available within a year of the lockdown.

“So, if we invest in studying animal viruses early and understanding their biology in greater depth, we’ll be better positioned to combat them later,” Warren said.

“We are continually going to be exposed to the viruses of animals. Things are never going to change if we stay on the same trajectory,” he said. “And if we stay complacent and only study those animal viruses after they jump into humans, we’re constantly going to be working backward. We’ll always be behind.”