Scientists share what they’ve learned about the people who lived on a stretch of coastline in Quintana Roo, Mexico, for over 3,000 years after more than a decade of research.

Dr. Jeffrey Glover, an anthropologist at Georgia State University, grew up in Atlanta, but it sounds like his heart is in Quintana Roo. An extensive research project spanning more than ten years has been based in this part of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. His collaboration with Dr. Dominique Rissolo, a maritime archaeologist at UC San Diego’s Qualcomm Institute, has yielded thousands of artifacts that have shed new light on the ancient Maya people who lived along this stretch of coast.

Glover and Rissolo are collaborating with an interdisciplinary and international team of researchers to gain new insights into the dynamic interplay of social and natural processes that has shaped life for the Maya people over the last 3,000 years. The team has just published a new article summarizing their findings to date in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology.

“The Proyecto Costa Escondida,” or “hidden coast” project, has concentrated on the ancient Maya port sites of Vista Alegre and Conil.

“The project name was chosen because the coast is literally hidden behind mangroves. We canoed along the coast, and you really have to snake back to get to the site “Glover stated. “But, more importantly, this region has been hidden from scholarship — there simply hadn’t been much work done there until we arrived.”

Since 800 BCE, the work has produced a wealth of knowledge about the maritime Maya civilization (Before Common Era). Glover, an associate professor of Anthropology, is attempting to better understand the dynamic relationship between humans and the environment at the ancient Maya port sites of Vista Alegre and Conil by employing a historical ecology framework.

“This is about how people respond to change,” said Dr. John Yellen, archeology program director at the National Science Foundation in the United States, which helped fund the research. “This diverse group of researchers has demonstrated how the Maya adapted over centuries to a wide range of environmental changes using the lens of historical ecology. This understanding of one society’s long-term adaptation to coastal environments provides a useful model for researching such interactions across many cultures.”

Our research gives us some idea of the shared challenges that coastal peoples faced — rising sea levels, diminishing freshwater resources, changing economic and political systems — and they probably relied on one another.

Dr. John Yellen

This region is located on Yucatan’s north coast, a few hours’ drive from popular tourist destinations such as Cancun and well-known archaeological sites such as Chichen Itza and Tulum.

“What’s remarkable about our study area is that it represents one of the least developed coastlines on the northern Yucatan Peninsula,” said Rissolo, who was recently featured in a video series about the Maritime Maya. “When trying to understand the ancient maritime cultural landscape of the so-called ‘Riviera Maya,’ for example, your perspective is obscured by all-inclusive resorts, golf courses and theme parks. The shores of the Laguna Holbox, on the other hand, are still largely wild and offer a more unobstructed view into the region’s past.”

Tens of thousands of artifacts and ecofacts (animal and plant remains that speak to past diets) have been discovered, which has improved our understanding of how the landscape has changed over time, how people lived, and how they dealt with challenges similar to those faced by people today, such as rising sea levels and changing political and economic systems. “We’re coordinating and synthesizing all of the different datasets that we have, which gives us a broader picture,” Glover explained.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) funded the project, which combines traditional archaeological techniques (think digging with a small hand trowel or shovel) with new, high-tech land and sea practices. Glover says it is a matter of making the most out of the materials at hand.

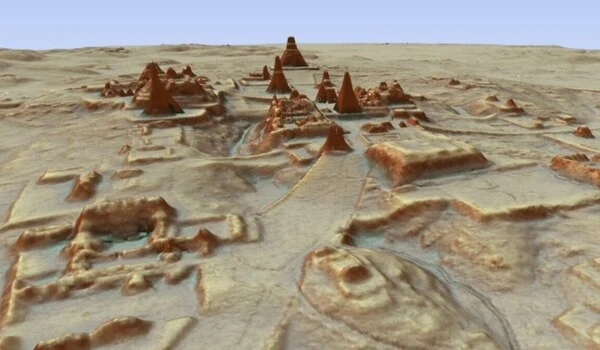

The complex work of marine geoarchaeology was spearheaded by Dr. Beverly Goodman-Tchernov and Dr. Roy Jaijel of the University of Haifa in Israel. The core samples include sediment from the coastline and give researchers a better idea of how the coastline has changed over time by looking at a host of different datasets. In particular, the remains of tiny creatures (foraminifera) are preserved in the cores. These creatures lived in very specific environments, so by finding certain species of foraminifera, the team can reconstruct what the coastal environment was like. Instead of being hidden as it is today, Vista Alegre was most likely once more open and purposely built on a peninsula that jutted into the lagoon making it a more obvious destination for ancient canoe-based traders.

The team also discovered tens of thousands of pieces of pottery and hundreds of pieces of obsidian (volcanic glass used to make tools and traceable to its original geologic location), indicating that these coastal peoples engaged in extensive trade. Glover claims that the variety of these artifacts stands out when compared to nearby inland sites. The archaeological data, according to the research team, support the idea that these coastal peoples had much broader and more cosmopolitan connections because they were part of long-distance, canoe-based trade networks.

Researchers see a major realignment and expansion in international trade associated with the emergence of Chichen Itza as a powerful religious, political, and economic city around 1,000 years ago.

“Strong evidence of this realignment comes from the obsidian data which reveals greater connections to parts of central Mexico, near modern day Mexico City” Glover said.

In addition, the team discovered a variety of natural materials, including over 20,000 animal bones from sharks, rays, turtles, and marine gastropods (gastropods include animals like conchs and whelks which have been studied by another project leader, Dr. Derek Smith). The team is collaborating with Mexican archeologists at the Autonomous University of Yucatan in Merida, Mexico, to analyze the discovered animal remains and burial sites.

Despite the fact that research was halted for much of the pandemic, the team is still working to analyze their findings after months of excavations and the discovery of so many artifacts. Glover also stated that they are in talks with local leaders in Mexico about establishing a community museum to highlight the region’s rich cultural and natural history.

The study also emphasizes the specific lifestyles and adaptive strategies required to live in a dynamic coastal environment, as well as how this fostered a sense of community among coastal Maya communities.

“Our research gives us some idea of the shared challenges that coastal peoples faced — rising sea levels, diminishing freshwater resources, changing economic and political systems — and they probably relied on one another,” Glover said. “In some ways, I believe it would have been easier to jump in your canoe and paddle down the coast to seek help than it would have been to walk over land.”