Bees have been observed telling time using light and social cues. Now, postdoctoral scholar in biological sciences Manuel Giannoni-Guzmán and colleagues from Brandeis University, the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras, the University of Pittsburgh, and East Tennessee State University have demonstrated that temperature cycles inside the hive can affect bees’ circadian clocks.

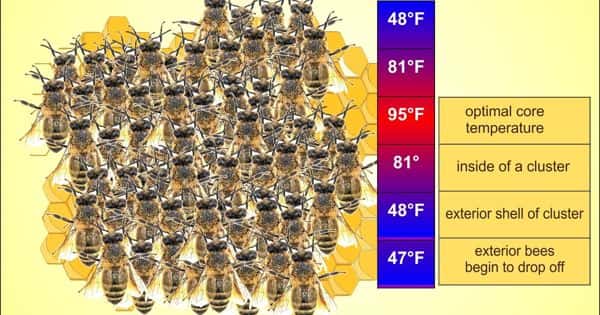

Temperature cycles inside the hive, according to Vanderbilt University researchers, can alter bees’ circadian clocks. They placed bees in complete darkness while exposing them to the temperature cycles observed within the colony. When they later shifted the temperature cycle back by six hours, the bees’ activity shifted with it.

Researchers have shown that the internal clocks of bees are driven by temperature cycles inside their hives. The researchers sought to better understand how bees lived in areas beyond where light enters the hive.

The researchers wanted to learn more about how bees lived in areas where light did not enter the hive. They were surprised to discover clear temperature fluctuations throughout the day in the hive, mimicking temperature oscillations caused by daylight.

To determine how important this temperature cycle was to a bee’s activity, the researchers placed bees in complete darkness while exposing them to the temperature cycles observed within the colony. Six days later, the temperature cycle was shifted back by six hours. “We saw that the bees shifted their activity with the temperature, meaning their daily routines were responsive to temperature,” Giannoni-Guzmán said.

The discovery that bees can tell accurate time from temperature cycles inside the hive indicates that when it’s cloudy or bees aren’t going outside, they have other ways to tell time accurately. This will have an impact on how researchers understand, interpret, and integrate their knowledge of bee behavior.

More broadly, as more extreme weather events occur around the world, bees will face difficulties in continuing to perform the activities that keep them and the agriculture they support healthy and vibrant. If the southern United States experiences an unexpected snowstorm, bees preparing to forage may not realize they need to conserve energy and heat the hive. In the event of a 100-degree day, bees will have to expend a significant amount of energy in order to keep the colony cool. These factors will influence colony health or colony collapse, according to Giannoni-Guzmán.

Environmental time cues, known as Zeitgebers, synchronize circadian clocks. Daily oscillations in environmental factors such as temperature and light are examples of Zeitgebers, as are daily recurring feeding times and social interactions. In the absence of a circadian clock, synchronization of bee emergence may occur solely through a periodic environmental time cue (Zeitgeber). The advantage of a circadian clock, on the other hand, is that the daily rhythms are maintained in the absence of the Zeitgeber.

This discovery also indicates that bees have other methods for accurately describing time on cloudy days. When extreme temperatures occur, bees will face difficulties in carrying out the activities that keep them and the agriculture they support healthy and vibrant.

“We want to see how important this research is in the winter in Tennessee, when bees don’t leave the hive as much,” Giannoni-Guzmán explained. “We’ll be curious to see how our findings apply to temperate regions with greater temperature variability throughout the year.” This study will also change the way researchers think about bees’ circadian rhythms.