According to a Dartmouth study, there is a solid scientific foundation for allegations of individual country climate culpability. The study is the first to evaluate the economic effects that certain nations have had on other nations as a result of their total national contributions to global warming.

In 143 of the nations for which data are available, the study establishes clear correlations between national emissions of heat-trapping gases and losses and gains in GDP. The study, which was published in the journal Climatic Change, gives countries a crucial legal foundation on which to base their claims for financial losses related to emissions and global warming.

“Greenhouse gases emitted in one country cause warming in another, and that warming can depress economic growth,” said Justin Mankin, an assistant professor of geography at Dartmouth and senior researcher of the study. “This research provides legally valuable estimates of the financial damages individual nations have suffered due to other countries’ climate-changing activities.”

Among the data, the study discovered that from 1990 to 2014, a small number of the world’s top national emitters of greenhouse gases contributed to $6 trillion in global economic losses due to warming.

The two biggest polluters in the world, the United States and China, are said to be responsible for over $1.8 trillion in losses in global revenue over the 25 years starting in 1990.

For the same years, Russia, India, and Brazil collectively generated economic losses of more than $500 billion. The $6 trillion in total losses attributable to the five countries throughout the study period is equivalent to around 11% of the yearly world GDP.

“This research provides an answer to the question of whether there is a scientific basis for climate liability claims the answer is yes,” said Christopher Callahan, first author of the study and a PhD candidate at Dartmouth. “We have quantified each nation’s culpability for historical temperature-driven income changes in every other country.”

Warmer weather can harm a nation’s economy in a number of ways, including by lowering agricultural yields, lowering worker productivity, or lowering industrial output.

Greenhouse gases emitted in one country cause warming in another, and that warming can depress economic growth. This research provides legally valuable estimates of the financial damages individual nations have suffered due to other countries’ climate-changing activities.

Justin Mankin

The study evaluates both the losses and the economic advantages associated with global warming brought on by country-level emissions, but it also emphasizes that these huge gains, which disproportionately benefit some nations, do not cancel out the losses experienced by others. The study does not consider additional effects of emissions, such as those on air quality, but only the economic costs of a temperature change as a result of emissions.

The study’s data estimates economic effects depending on various accounting methodologies for greenhouse gas emissions, taking into account emissions that occurred within a nation’s borders as opposed to emissions included in international trade.

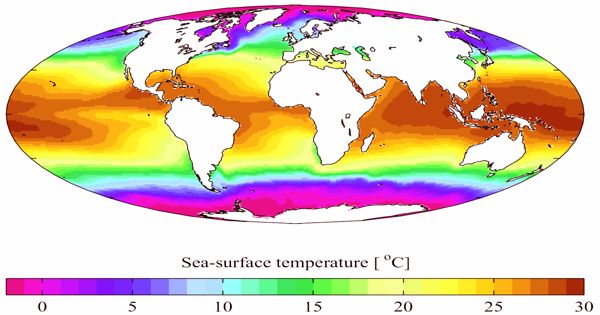

The study demonstrates the extreme inequality in the distribution of warming impacts from emitters, with the top 10 global emitters responsible for more than two-thirds of global losses. Countries that experience revenue losses are typically found in the tropics and the global south, where they are warmer and poorer than the average country. Income-producing nations are typically found in the middle latitudes and the north, where they are generally colder and wealthier than the world average.

“Irrespective of the accounting, warm counties have warmed and lost income because of it, while colder countries have warmed but enjoyed economic gains,” said Mankin. “The responsibility for the warming rests primarily with a handful of major emitters, and this warming has resulted in the enrichment of a few wealthy countries at the expense of the poorest people in the world.”

Researchers have been trying to prove in court that economic damage and emissions of greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide are directly related. Previous studies have estimated the entire level of economic loss on a global scale, but they were unable to pinpoint the amount of warming that was caused by specific countries, undercutting national efforts to hold polluting states liable for financial losses due to the uncertainties involved.

The Dartmouth research team aims to address issues of national accountability to inform climate policy by developing an analytical framework that connects emissions from particular countries to the losses and gains in every other country.

“For the first time, we have been able to show clear and statistically significant linkages between the emissions of specific countries and historical economic losses experienced by other countries,” said Callahan. “This is about the culpability of one country to another country, not the effect of overall global warming on a country.”

According to the team, the study refutes the notion that mitigating climate change is merely a “collective action problem,” in which no one nation acting alone can have an impact on the effects of global warming.

“Until now, the complexity of the carbon cycle, natural variations in climate, and uncertainties in models have provided emitters with plausible deniability for individual damage claims. That veil of deniability has now been lifted,” said Mankin.

According to the team, determining national culpability demonstrates that individual nations’ actions do matter and that country-level mitigation, even if pursued independently, would limit quantifiable harm to others. Individual nations can have significant, attributable warming impacts as a result of their emissions.

“Nations need to work together to stop warming, but that doesn’t mean that individual countries can’t take actions that drive change,” said Callahan. “This research upends the notion that the causes and impacts of warming only occur at the global level.”

Accounting for significant uncertainties at each point in the causal chain from emissions to global warming, from warming to country-level temperature changes, and from country-level temperature changes to impact posed a significant problem for the research.

This challenge was overcome by the research team by integrating climate models and historical data into a framework that quantified the responsibility of each nation for past temperature-driven income changes in every other country.

2 million potential values for each country-to-country interaction were sampled in the study. On a supercomputer run by Dartmouth’s Research Information, Technology and Consulting, 11 trillion values were calculated in total.

“This is the first research to integrate and quantify all of the uncertainties in each step of the chain between emissions and economic impact,” said Callahan. “We are not addressing the question of whether fossil fuels have been good or bad for economic growth, but how to compensate for the damage caused by the warming from those emissions.”

Future study can apply the same analytical strategy, according to the research team, to ascertain the impact of specific emitters, including individual firms, to economic gain and loss.

The Wright Center for the Study of Computation and Just Communities, a research institute inside Dartmouth’s Neukom Institute for Computational Science, provided funding for the study. The Graduate Research Fellowship program of the National Science Foundation also contributed to funding.