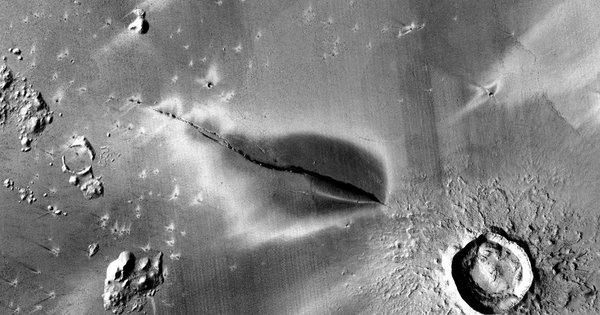

A volcano is a fissure or vent in the Earth’s surface through which molten rock and gases are expelled. Volcanoes directly or indirectly produce or host deposits of aluminum, diamonds, gold, nickel, lead, zinc, and copper. Planetary scientists from Rice University, NASA’s Johnson Space Center, and the California Institute of Technology have solved a mystery that has baffled the Mars research community since NASA’s Curiosity rover discovered tridymite in Gale Crater in 2016.

Tridymite is a high-temperature, low-pressure form of quartz that is extremely rare on Earth, and it was unclear how a concentrated chunk of it ended up in the crater. GaleCrater was chosen as Curiosity’s landing site due to the likelihood that it once held liquid water, and Curiosity found evidence that confirmed Gale Crater was a lake as recently as 1 billion years ago.

“The discovery of tridymite in a mudstone in Gale Crater is one of the most surprising observations that the Curiosity rover has made in 10 years of exploring Mars,” said Rice’s Kirsten Siebach, co-author of a study published online in Earth and Planetary Science Letters. “Tridymite is usually associated with quartz-forming, explosive, evolved volcanic systems on Earth, but we found it in the bottom of an ancient lake on Mars, where most of the volcanoes are very primitive.”

The discovery of tridymite in a mudstone in Gale Crater is one of the most surprising observations that the Curiosity rover has made in 10 years of exploring Mars.

Kirsten Siebach

Siebach is a mission specialist on NASA’s Curiosity team and an assistant professor in Rice’s Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences. She collaborated with two postdoctoral researchers in her Rice research group, Valerie Payré, and Michael Thorpe, NASA’s Elizabeth Rampe, and Caltech’s Paula Antoshechkina to solve the mystery. Payré, the study’s lead author, is now at Northern Arizona University and will join the University of Iowa faculty in the fall.

Siebach and colleagues began by reevaluating data from every reported tridymite find on the planet. They also reexamined sedimentary evidence from the Gale Crater lake and reviewed volcanic materials from Mars volcanism models. They then devised a new scenario that matched all of the evidence: Martian magma sat in a chamber beneath a volcano for longer than usual, undergoing a partial cooling process known as fractional crystallization, which concentrated silicon.

The volcano erupted in a massive eruption, spewing ash containing extra silicon in the form of tridymite into the Gale Crater lake and surrounding rivers. Water aided in the breakdown of ash through natural chemical weathering processes, and it also aided in the separation of minerals produced by weathering.

The scenario would have concentrated tridymite, producing minerals consistent with the 2016 find. It would also explain other geochemical evidence Curiosity found in the sample, including opaline silicates and reduced concentrations of aluminum oxide.

“It’s actually a straightforward evolution of other volcanic rocks we found in the crater,” Siebach said. “We argue that because we only saw this mineral once, and it was highly concentrated in a single layer, the volcano probably erupted at the same time the lake was there. Although the specific sample we analyzed was not exclusively volcanic ash, it was ash that had been weathered and sorted by water.”

If a volcanic eruption similar to the one depicted in the scenario occurred when Gale Crater contained a lake, it would imply that explosive volcanism occurred more than 3 billion years ago, when Mars was transitioning from a wetter and possibly warmer world to the dry and barren planet it is today.

“There is plenty of evidence of basaltic volcanic eruptions on Mars, but this is a more evolved chemistry,” she explained. “This research suggests that Mars may have a more complex and intriguing volcanic history than we previously imagined.”

The Curiosity rover is still operational, and NASA is gearing up to mark the tenth anniversary of its landing next month.