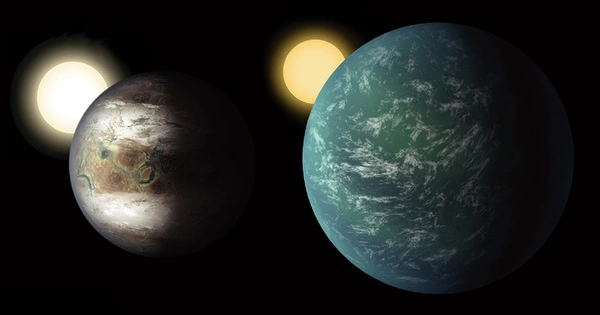

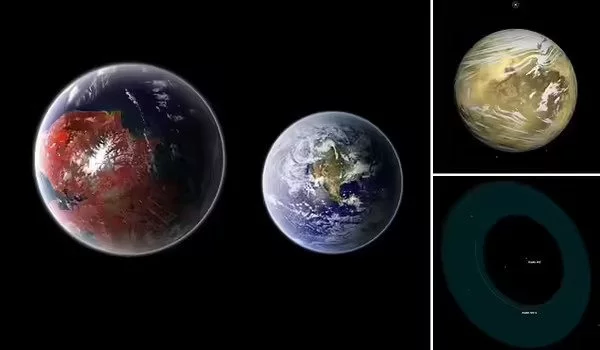

Astronomers have discovered evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star are ‘water worlds,’ or planets where water makes up a large proportion of the volume. A team led by UdeM astronomers discovered evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star are “water worlds,” or planets where water makes up a large proportion of the volume. These worlds, found in a planetary system 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, are unlike any planets in our solar system.

The team, led by Ph.D. student Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) at the Université de Montréal, published a detailed study of a planetary system known as Kepler-138 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Piaulet, a member of Björn Benneke’s research team, used NASA’s Hubble and the retired Spitzer space telescopes to observe exoplanets Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d and discovered that the planets, which are about one and a half times the size of Earth, could be mostly made of water. NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope had previously discovered these planets as well as a planetary companion closer to the star, Kepler-138b.

The temperature in the atmospheres of Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d is likely to be above the boiling point of water, and we anticipate a thick, dense atmosphere of steam on these planets. Only in that steam atmosphere could liquid water at high pressure exist, or even water in another phase that occurs at high pressures, known as a supercritical fluid.

Caroline Piaulet

Water was not directly detected, but by comparing the planets’ sizes and masses to models, they conclude that a significant fraction of their volume – up to half – should be made of materials lighter than rock but heavier than hydrogen or helium. Water is the most common of these candidate materials.

“We previously thought that planets that were a bit larger than Earth were big balls of metal and rock, like scaled-up versions of Earth, and that’s why we called them super-Earths,” explained Benneke. “However, we have now shown that these two planets, Kepler-138c and d, are quite different in nature: a big fraction of their entire volume is likely composed of water. It is the first time we observe planets that can be confidently identified as water worlds, a type of planet that was theorized by astronomers to exist for a long time.”

With volumes more than three times that of Earth and masses twice as big, planets c and d have much lower densities than Earth. This is surprising because most of the planets just slightly bigger than Earth that have been studied in detail so far all seemed to be rocky worlds like ours. The closest comparison to the two planets, say researchers, would be some of the icy moons in the outer solar system that are also largely composed of water surrounding a rocky core.

“Think of larger versions of Europa or Enceladus, the water-rich moons that orbit Jupiter and Saturn, but brought much closer to their star,” Piaulet explained. “Kepler-138 c and d would have large water-vapor envelopes instead of an icy surface.”

Researchers warn that the planets may not have oceans like Earth’s directly on their surfaces. “The temperature in the atmospheres of Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d is likely to be above the boiling point of water, and we anticipate a thick, dense atmosphere of steam on these planets. Only in that steam atmosphere could liquid water at high pressure exist, or even water in another phase that occurs at high pressures, known as a supercritical fluid” said Piaulet.

Recently, another team at the University of Montreal found another planet, called TOI-1452 b, that could potentially be covered with a liquid-water ocean, but NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will be needed to study its atmosphere and confirm the presence of the ocean.

A new exoplanet in the system

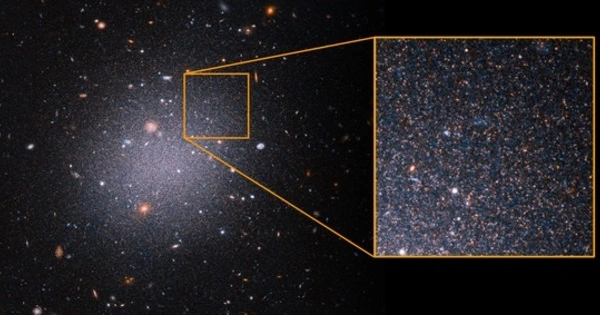

Astronomers announced the discovery of three planets orbiting Kepler-138, a red dwarf star in the constellation Lyra, using data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope in 2014. This was based on a measurable dip in starlight caused by the planet passing in front of their star for a brief moment, known as a transit.

Benneke and his University of New Mexico colleague Diana Dragomir devised the plan to re-observe the planetary system with the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes between 2014 and 2016 in order to catch more transits of Kepler-138d, the system’s third planet, in order to study its atmosphere.

While earlier NASA Kepler space telescope observations only showed transits of three small planets around Kepler-138, Piaulet and her team were surprised to find that the Hubble and Spitzer observations suggested the presence of a fourth planet in the system, Kepler-138e.

This newly discovered planet is small and far from its star, taking 38 days to complete an orbit. The planet is in its star’s habitable zone, a temperate region in which a planet receives just the right amount of heat from its cool star to be neither too hot nor too cold to support liquid water.

The nature of this additional, newly discovered planet, on the other hand, remains unknown because it does not appear to transit its host star. The transit of the exoplanet would have allowed astronomers to calculate its size.

With Kepler-138e now in the picture, the masses of the previously known planets were measured again via the transit timing-variation method, which consists of tracking small variations in the precise moments of the planets’ transits in front of their star caused by the gravitational pull of other nearby planets.

Another surprise was discovered by the researchers: the two water worlds Kepler-138c and d are “twin” planets, with nearly the same size and mass, despite previously being thought to be vastly different. Kepler-138b, on the other hand, has been confirmed to be a small Mars-mass planet, one of the smallest exoplanets discovered to date.

“As our instruments and techniques improve, we may find a lot more water worlds like Kepler-138 c and d as our instruments and techniques become sensitive enough to find and study planets that are farther from their stars,” Benneke concluded.