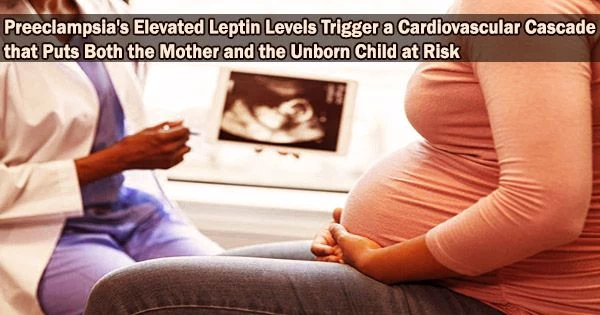

Critical supply chain issues with nutrition and oxygen can cause premature delivery or even death before a baby is ever born, raising the risk of cardiovascular disease for both the mother and the kid for the rest of their lives.

In preeclampsia, which puts both mother and baby at risk, researchers have discovered that a midgestational rise in the hormone leptin, which most of us identify with appetite reduction, causes serious blood vessel malfunction and limits the baby’s growth.

Preeclampsia is known to cause an increase in leptin production by the placenta around 20 weeks into a pregnancy, but the effects have not yet been determined.

“It’s kind of emerging as a marker of preeclampsia,” says Dr. Jessica Faulkner, vascular physiologist in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia and corresponding author of the study in the journal Hypertension.

“Leptin, mostly produced by fat cells, is also produced by the temporary organ, the placenta, which enables the mom to supply her developing baby with nutrients and oxygen,” Faulkner says.

In a healthy pregnancy, leptin levels gradually rise, but it’s unclear exactly what leptin is doing in this situation, even normally. There is some evidence that it functions as a natural nutrient sensor during reproduction or as a way to promote the growth of new blood vessels and/or growth hormone for normal development.

“But in preeclamptic patients leptin levels go up more than they should,” Faulkner says.

For the first time, new research examining the effects demonstrates that an increase in leptin causes endothelial dysfunction, which causes blood vessels to contract, lose their ability to relax, and limit a baby’s growth.

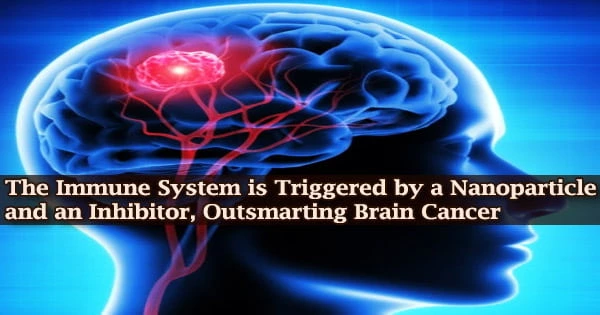

The scientists were able to almost exactly duplicate the effects of the midgestation leptin increase by inhibiting the precursor for the potent, naturally occurring blood vessel dilatant nitric oxide, as occurs in hypertension.

We think what is going on in preeclamptic patients is the placenta is not properly formed. “In the middle of gestation, fetal growth is not happening as it should. I think the placenta is compensating by increasing leptin production,” potentially with the goal of helping spur more normal growth. But the results appear to be just the opposite.

Dr. Jessica Faulkner

To make matters worse, the scientists also have evidence that leptin plays a role in increasing levels of the blood vessel constrictor endothelin 1.

“Conversely when they deleted the receptor for aldosterone, in this case the mineralocorticoid receptors on the surface of the cells that line blood vessels, endothelial dysfunction didn’t happen,” says Dr. Eric Belin de Chantemele, physiologist in MCG’s Vascular Biology Center and the paper’s senior author.

“We think what is going on in preeclamptic patients is the placenta is not properly formed,” Faulkner says. “In the middle of gestation, fetal growth is not happening as it should. I think the placenta is compensating by increasing leptin production,” potentially with the goal of helping spur more normal growth. But the results appear to be just the opposite.

“It can hurt the baby’s development and increase the risk of long-term health problems for the baby and mother,” she says.

“While leptin has been associated with preeclampsia, this was the first study to show that when leptin goes up, it induces the unhealthy clinical characteristics of preeclampsia,” Belin de Chantemele says.

Infusing leptin into pregnant mice caused an unhealthy chain reaction that resulted in the adrenal gland producing more of the steroid hormone aldosterone, which could be increasing the production of endothelin 1 by the placenta as well.

Their earlier research has demonstrated that a leptin infusion causes endothelial dysfunction outside of pregnancy. Belin de Chantemele’s lab has pioneered work showing that fat-derived leptin directly prompts the adrenal glands to make more aldosterone which activates mineralocorticoid receptors found throughout the body, notably in the blood vessels in females, which is important to blood pressure levels. High levels of aldosterone are a hallmark of obesity and a major contributor to metabolic and cardiovascular issues.

They came to the conclusion from their research that the midgestational leptin infusion in preeclampsia had a similar effect to what could be achieved by deleting the mineralocorticoid receptors lining blood vessels. In young females, where obesity frequently robs the early years of protection from cardiovascular disease that being female typically provides until menopause, they have linked similar physiological dots.

“These same players likely are factors in what increases the mother’s lifetime risk of cardiovascular problems,” Faulkner says.

“It means the system is dysregulated and that is basically when you develop disease,” she says.

Their goals include better defining the pathways for increased blood pressure and other blood vessel dysfunction, pathways that can be targeted during pregnancy to prevent potentially devastating results for mother and baby, from what Faulkner characterizes as “a two-hit condition.”

Their findings to date indicate that effective therapies to better protect mother and baby could be existing drugs like eplerenone, a blood pressure medicine that binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor effectively reducing the effect of higher levels of aldosterone, the scientists say.

The temporary organ may not receive adequate blood flow early in its development, which may lead to failure of the development of the large blood vessels that eventually become the route for nutrients and oxygen from the mother to the fetus.

Preeclampsia is known to cause issues, such as decreased placental growth factor secretion. The bottom line appears to be that by midgestation, the placenta is unable to sustain the fetus adequately.

As a result, it may secrete leptin, perhaps in an effort to promote its own growth and normal fetal development, but in actuality, the scientists report that this has negative effects on the mother’s blood pressure as well as cardiovascular and fetal outcomes.

“Preeclampsia rates unfortunately are rising,” Faulkner says, both in the number of pregnant women affected and in how severely they are affected.

According to an analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published in January of this year in the Journal of the American Heart Association, rates of hypertension that arise during pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, have nearly doubled in both rural and urban areas in this country from 2007-19 and have been accelerating since 2014.

Gestational hypertension is a rise in a pregnant woman’s blood pressure that does not come with preeclampsia-like symptoms like protein in the urine, renal discomfort, or indicators of placental failure.

Multiple pregnancy, persistent high blood pressure, type 1 or 2 diabetes, kidney disease, autoimmune disorders, use of in vitro fertilization, and multiple fetuses are all risk factors.

“Increasing rates of preeclampsia are primarily attributed to obesity, which is a risk factor for many of these conditions and associated with high levels of both aldosterone and leptin,” Faulkner says. Other times, women seem to develop the problem spontaneously.

“Next steps in the research include better understanding how and why leptin goes up more than it should,” Faulkner says.

The scientists are supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.