The millions of tons of plastic floating around the world’s oceans have recently received a lot of media attention. However, plastic pollution may pose a greater threat to land-based plants and animals, including humans.

Microplastics are posing an increasing threat to global agriculture and food production, according to new research. Staffordshire University scientists are leading research to better understand the extent of plastic pollution in agricultural soils and its global impact.

Plastic pollution will have long-term consequences for future generations. If current levels of pollution continue, experts predict that there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish by 2050. It is obvious that we require solutions to address this pressing issue.

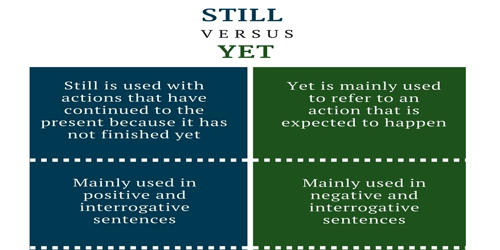

Claire Gwinnett, Professor of Forensic and Environmental Science, explained: “We know a lot about microplastics in oceans and freshwater and we are starting to learn more about microplastics in the air, but we still know very little about microplastics in terrestrial environments.

“With climate change, the pressure of increasing populations on food production and risks to food security, it has become apparent that it is incredibly important that we look into this.”

Plastic use in agriculture may provide valuable benefits in the short term, but the long-term consequences cannot be overlooked. We hope that our growing body of research can be used to inform decision-makers and spark real change to protect soil health and farming’s future.

Professor Gwinnett

The use of plastics in agriculture has increased significantly in recent years. Microplastics in soil, on the other hand, are estimated to take up to 300 years to degrade completely. It is believed that their presence alters soil characteristics such as structure, water holding capacity, and microbial communities and that microplastics are partly responsible for crop-reducing effects.

The Staffordshire Forensic Fibres and Microplastic Research Group has been conducting various studies, including an international review of the pressures of plastic pollution in rural areas, which highlights the need for more extensive analysis of terrestrial microplastics to help reduce environmental and public health threats.

Professor Gwinnett said: “We know that microplastics in agricultural soils are abundant, varied, and are influenced by land use and farming activities. We know from a small number of studies that it can affect organisms living in the soil such as worms and springtails.

“Studies on the effect of microplastics on plants are even rarer but we also know that it impacts crops grown in these environments as well as livestock living there. What we need to know now is how much plastic there is and to better understand what effect this is having.”

Ellie Harrison, a Ph.D. researcher with the Staffordshire Forensic Fibres and Microplastic Research Group, is currently conducting a series of studies on the effects of microplastics on commonly grown crops in the United Kingdom. “Research at Staffordshire University into the impacts of microplastics in agricultural soils has shown that this pollutant can cause a decrease in germination rate and changes to seed production, which could have negative consequences for food production,” she said.

A recent study conducted in collaboration with ukurova University looked at the amount of plastics derived from disposable greenhouse plastic films and irrigation pipes in Turkish agricultural soils.

Professor Gwinnett said: “Greenhouse films and irrigation piping are products commonly used in farming and we have the same plastic uses in the UK and across Europe. Instead of being removed, these plastic products are often left in fields where they experience wear and tear and degradation from the sun which breaks these plastics down into secondary microplastics.

“Our findings show that after years of using these plastics, microplastics have accumulated in the soil and cannot be removed.”

Soil samples were collected from ten different sites in Turkey’s Adana/Karata region. The number of micro-, meso-, macro-, and megaplastics found in soil where greenhouse film and irrigation piping were used was approximately 47, 78, 17, and 1.2-times higher than in farmlands that did not use plastic, respectively. The results showed that residual plastics were reduced in soil where used plastics were removed after use. The findings are intended to assist farmers in better managing plastics.

A further study with Çukurova University is investigating farmer practices and perceptions in Turkey to understand what the barriers are to taking up preventative measures or more sustainable approaches.

Staffordshire University has been conducting similar research in the UK in partnership with the National Farmers’ Union (NFU); this study looks into the amount and types of microplastic in UK agricultural soils. This is the first study of its kind in the UK, and it aims to learn more about the extent of microplastic pollution in farmland.

Professor Gwinnett continued: “Plastic use in agriculture may provide valuable benefits in the short term, but the long-term consequences cannot be overlooked. We hope that our growing body of research can be used to inform decision makers and spark real change to protect soil health and farming’s future.”