In a recent study, Feng “Frank” Xiao and associates from the University of Missouri show how to quickly break down PFAS that have been left on the surface of two solid materials, granular activated carbon and anion exchange resins, after these materials have been used to filter PFAS from public water systems. They do this by using a novel technique called thermal induction heating. The team’s goal is to clean the materials before they are properly disposed.

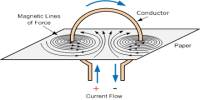

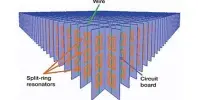

A class of synthetic compounds known as PFAS is frequently discovered in consumer and commercial goods like nonstick cookware, firefighting foam, and food packaging. The procedure involves electromagnetic induction inside a metallic reactor and is based on the Joule heating phenomenon.

“In this study, we explored the use of an engineering technique used to melt metals,” Xiao said. “This method produced 98% degradation of PFAS on the surface of absorbents like granular activated carbon and anion exchange resins after just 20 seconds, which makes this process highly energy efficient and much faster than conventional methods.”

In recent years, experts have expressed alarm over the risks that PFAS exposure poses to human health, including the possibility of developing cancer and other serious illnesses.

Xiao, whose appointment is in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said while PFAS can be filtered out of water using adsorbents, the disposal of used or “spent” adsorbents also creates issues of environmental contamination.

“Since the group of chemicals known as PFAS generally resist degradation, they pose considerable challenges to established treatment processes, including the waste disposal practices for materials used as filters like granular activated carbon and anion exchange resins,” Xiao said.

If the gaseous organic fluorinated products are not degraded during induction heating, abatement treatment will be necessary to remove or degrade them. However, based on my previous studies, some of these products can be degradable by regular thermal approaches. Simultaneously, the generation of hydrogen fluoride is increased, which is desirable because it means greater mineralization, or decomposition, of PFAS. We’ve found hydrogen fluoride can be removed simply using clay or soil at moderate temperatures.

Feng “Frank” Xiao

PFAS removal from the environment has been the focus of Xiao’s career-long research, and he recently demonstrated a similar level of effectiveness by using induction heating to quickly decompose PFAS in soil.

He said the current study also drew inspiration from recent proposed regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that, if finalized, would require public water systems in the U.S. to monitor and reduce PFAS contamination in drinking water and spent adsorbents.

By-products produced during this procedure, such as organic fluorinated species and hydrogen fluoride, are potential downsides of this approach. While these by-products are considered toxic to consume through breathing or ingestion, Xiao has a solution.

“If the gaseous organic fluorinated products are not degraded during induction heating, abatement treatment will be necessary to remove or degrade them,” Xiao said. “However, based on my previous studies, some of these products can be degradable by regular thermal approaches. Simultaneously, the generation of hydrogen fluoride is increased, which is desirable because it means greater mineralization, or decomposition, of PFAS. We’ve found hydrogen fluoride can be removed simply using clay or soil at moderate temperatures.”

“Thermal phase transition and rapid degradation of forever chemicals (PFAS) in spent media using induction heating,” was published in ACS ES&T Engineering, a journal of the American Chemical Society.

The study was funded the U.S. National Science Foundation CAREER Program, the U.S. Department of Defense SERDP, and the U.S. Geological Survey. The authors alone are responsible for the material, which does not necessarily reflect the funding organizations’ official positions.