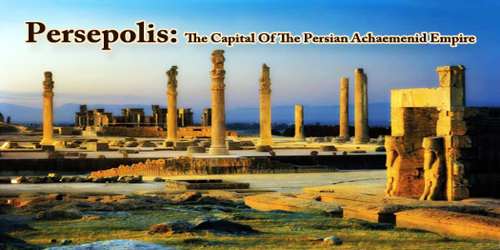

Persepolis (/pɝˈsepəlɪs/, Old Persian: Pārsa) modern Takht-e Jamshīd or Takht-i Jamshīd (Persian: “Throne of Jamshīd,” Jamshīd being a character in Persian mythology), was the capital of the Persian Achaemenid Empire from the reign of Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) until its destruction in 330 BCE. It is situated 60 kilometers (37 mi) northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province, Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

The city was located in a remote region in the mountains, however, making travel there difficult in the rainy season of the Persian winter, so the administration of the Achaemenid Empire was also overseen from Ecbatana, Babylon, and Susa. Persepolis was a spring/summer royal residence and seems to have been intended as a ceremonial center where representatives of subject states came to pay respects to the king.

(Gate of All Nations, Persepolis)

The English word Persepolis is derived from Ancient Greek: Περσέπολις, romanized: Persepolis, a compound of Pérsēs (Πέρσης) and pólis (πόλις), meaning “the Persian city” or “the city of the Persians”. To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Pārsa (Old Persian), which is also the word for the region of Persia.

An inscription left in AD 311 by Sasanian prince Shapur Sakanshah, the son of Hormizd II, refers to the site as Sad-stūn, meaning “Hundred Pillars”. Because medieval Persians attributed the site to Jamshid, a king from Iranian mythology, it has been referred to as Takht-e-Jamshid (Persian: تخت جمشید, Taxt e Jamšīd; (ˌtæxtedʒæmˈʃiːd)), literally meaning “Throne of Jamshid”. Another name given to the site in the medieval period was Čehel Menār, literally meaning “Forty Minarets”.

The complex was comprised of nine structures:

- The Apadana (hypostyle receiving hall)

- Trachara (Palace of Darius I)

- Council Hall

- Treasury

- Throne Hall

- Palace of Xerxes I

- Harem of Xerxes I

- Gate of All Nations

- Tomb of the King

Of these nine, the first three were built by Darius I (who also began the treasury building) and the rest completed by his successors, notably his son Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) and grandson Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BCE). There were also residential buildings, a marketplace, and structures which archaeologists have yet to positively identify, at least one of which is most likely the palace of Artaxerxes I.

Persepolis is near the small river Pulvar, which flows into the Kur River. The site includes a 125,000 square meter terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Rahmat Mountain. The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which vary in height with the slope of the ground. Rising from 5-13 metres (16-43 feet) on the west side was a double stair. From there, it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

The terrace is a grandiose architectural creation, with its double flight of access stairs, walls covered by sculpted friezes at various levels, contingent Assyrianesque propylaea (monumental gateway), gigantic sculpted winged bulls, and remains of large halls. By carefully engineering lighter roofs and using wooden lintels, the Achaemenid architects were able to use a minimal number of astonishingly slender columns to support open area roofs. Columns were topped with elaborate capitals; typical was the double-bull capital where, resting on double volutes, the forequarters of two kneeling bulls, placed back-to-back, extend their coupled necks and their twin heads directly under the intersections of the beams of the ceiling.

The city’s remote location kept it a secret from the outside world, and it became the safest city in the Persian Empire for storing art, artifacts, archives, and keeping the royal treasury. The Greeks had no idea the city existed until it was sacked and plundered by Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) in 330 BCE, who burned it and carried off its vast treasures. The ruins lay buried until the 17th century CE when they were identified as the once-great royal city of Persepolis, but professional excavation did not begin until 1931 CE, with work continuing since.

The city was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was soon to be eclipsed by the new metropolis of Shīrāz. By the 10th century CE it had become an insignificant place, as may be seen from a description of it written by the Arab geographer al-Maqdisī (c. 985). In the mid-11th century the Seljuq emir Qutulmish razed it and transferred its population to Shīrāz.

The Apadana (audience hall) of Darius I at Persepolis, Iran

In 1933 two sets of gold and silver plates recording in the three forms of cuneiform Ancient Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian the boundaries of the Persian empire were discovered in the foundations of Darius’s hall of audience. A number of inscriptions, cut in stone, of Darius I, Xerxes I, and Artaxerxes III indicate to which monarch the various buildings were attributed. The oldest of these on the south retaining wall gives Darius’s famous prayer for his people: “God protect this country from foe, famine, and falsehood.” There are numerous reliefs of Persian, Median, and Elamite officials, and 23 scenes separated by cypress trees depict representatives from the remote parts of the empire who, led by a Persian or a Mede, made appropriate offerings to the king at the national festival of the vernal equinox.

Persepolis was the seat of government of the Achaemenid Empire, though it was designed primarily to be a showplace and spectacular centre for the receptions and festivals of the kings and their empire. The terrace of Persepolis continues to be, as its founder Darius would have wished, the image of the Achaemenid monarchy itself, the summit where likenesses of the king reappear unceasingly, here as the conqueror of a monster, there carried on his throne by the downtrodden enemy, and where lengthy cohorts of sculpted warriors and guards, dignitaries, and tribute bearers parade endlessly.

According to the historian Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), the city was ringed by three walls. When these walls were built or by whom is unknown since they were destroyed by Alexander the Great and nothing survives of them in the present day. The first wall, immediately around the terrace, was 23 feet (7 meters) high. The second, presumably with some interval between it and the first, was 46 feet high (14 meters), and the third rose to 89 feet (27 meters). These walls were topped by towers and always manned. A walkway, presumably, around the top enabled defense from any direction.

The function of Persepolis remains quite unclear. It was not one of the largest cities in Persia, let alone the rest of the empire, but appears to have been a grand ceremonial complex, that was only occupied seasonally; it is still not entirely clear where the king’s private quarters actually were. Until recent challenges, most archaeologists held that it was especially used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year, held at the spring equinox, and still an important annual festivity in modern Iran. The Iranian nobility and the tributary parts of the empire came to present gifts to the king, as represented in the stairway reliefs.

To the east side of the city is a royal tomb, though whose it is remains a matter of conjecture, and two miles (4 kilometers) to the northeast are the rock-cut cliff tombs of Darius I and his immediate successors. Those not interred in these tombs were buried at Persepolis, presumably in the area surrounding the eastern tomb.

In 330 BCE, during the reign of Darius III, Alexander plundered the city and burned the palace of Xerxes, whose brutal campaign to invade Greece more than a century before had led, eventually, to Alexander’s conquest of the Persian empire. In 316 BCE Persepolis was still the capital of Persis as a province of the Macedonian empire. The city gradually declined under the Seleucid kingdom and after, its ruins attesting its ancient glory.

It is believed that the fire which destroyed Persepolis started from Hadish Palace, which was the living quarters of Xerxes I, and spread to the rest of the city. It is not clear if the fire was an accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece. Many historians argue that, while Alexander’s army celebrated with a symposium, they decided to take revenge against the Persians. If that is so, then the destruction of Persepolis could be both an accident and a case of revenge.

The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century, describes Persepolis’ archives as containing “all the Avesta and Zend, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink”, which were destroyed. Indeed, in his Chronology of the Ancient Nations, the native Iranian writer Biruni indicates unavailability of certain native Iranian historiographical sources in the post-Achaemenid era, especially during the Parthian Empire. He adds: “Alexander burned the whole of Persepolis as revenge to the Persians, because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years ago. People say that, even at the present time, the traces of fire are visible in some places.”

The city lay crushed under the weight of its own ruin (although, for a time, nominally still the capital of the now-defeated empire) and was lost to time. It became known to residents of the area only as ‘the place of the forty columns’ owing to the still-remaining columns standing among the wreckage. In time, the site came to be associated with supernatural entities, was considered haunted, and was then generally avoided.

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, the Palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.

Although the fire had destroyed anything written on parchment, the clay tablets of cuneiform text were baked and then buried by rubble, preserving them. Among these are the Fortification Tablets (some 8,000 documents on the economics of the empire under Darius I), the Treasury Texts (administrative works from the reign of Artaxerxes I), and the so-called Travel Texts recording payments and rations given to travelers and their pack animals.

The archaeological ruins at Persepolis are authentic in terms of their locations and setting, materials and substance, and forms and design. The present location of the Persepolis terrace and its related buildings has not changed over the course of time. Restoration work has carefully respected the authenticity of the monuments, utilizing traditional technology and materials in harmony with the ensemble. No changes have been made to the general plan of Persepolis. Moreover, there are no modern reconstructions at Persepolis; the remains of all the monuments are authentic.

In 1971, Persepolis was the main staging ground for the 2,500 Year Celebration of the Persian Empire under the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty. It included delegations from foreign nations in an attempt to advance the Iranian culture and history. In the present day, it is an archaeological park located northwest of modern Shiraz, Iran, in the Fars province. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 CE and attracts visitors from around the world who come to experience the wonder that was once the great city of Persepolis.

Information Sources: