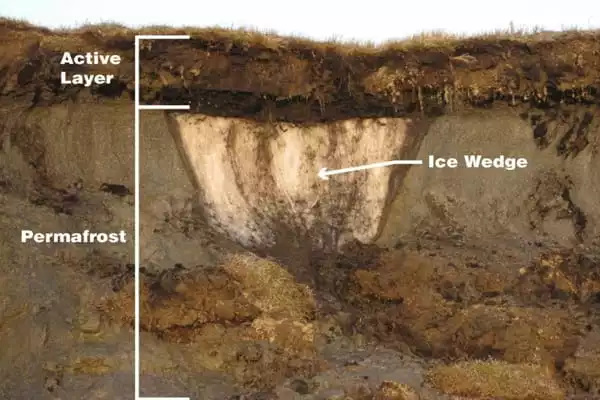

Permafrost is defined as any ground that has been fully frozen—32°F (0°C) or colder—for at least two years. These permanently frozen fields are particularly abundant in mountainous areas and at higher latitudes—near the North and South Poles. Permafrost blankets vast swaths of the planet. Permafrost covers over a fourth of the land area in the Northern Hemisphere. Permafrost locations are not always blanketed in snow, despite the fact that the ground is frozen.

The repercussions of Arctic permafrost thawing range from exacerbated climate change, increasing sea levels, and the potential release of toxins and infection to more immediate effects such as disruptions in livelihoods and damage to structures and infrastructure. Thawing permafrost in the Arctic may be releasing greenhouse gases from hitherto unaccounted-for carbon stores, contributing to global warming. The researchers discovered the source of carbon dioxide released from thousands of years old permafrost in the Siberian Arctic.

Thawing permafrost in the Arctic could be releasing greenhouse gases from hitherto unaccounted-for carbon stores, contributing to global warming. That is the conclusion of a study conducted by a team of geologists led by Professor Dr. Janet Rethemeyer at the University of Cologne’s Institute of Geology and Mineralogy, in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Hamburg and the Helmholtz Centre Potsdam — GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences. The research team discovered the source of carbon dioxide released from thousands of years old permafrost in the Siberian Arctic.

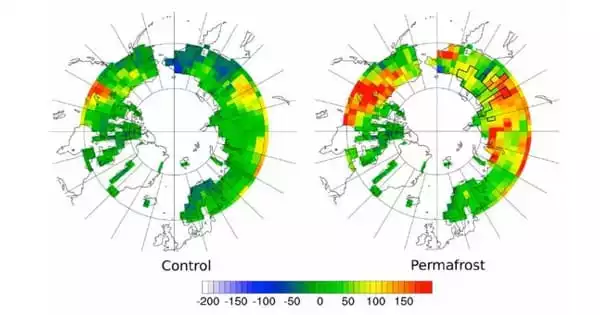

Thermokarst processes make previously frozen ground carbon accessible to microorganisms, which break it down and release it as carbon dioxide and methane. The greenhouse gas release amplifies global warming, which is known as permafrost-carbon feedback.

Professor Dr. Janet Rethemeyer

Temperatures are rising dramatically as a result of global climate change, particularly in the Arctic. Higher temperatures, for example, are driving an increase in the thawing of permafrost soils that have been frozen for thousands of years. The so-called ‘yedoma’ permafrost, which is common in places that were not covered by ice sheets during the previous ice age, is particularly vulnerable. Because Yedoma includes up to 80% ice, it is also known as an ice complex. Ground ice can thaw quickly, causing bedrock to collapse and erode. Thermokarst processes make previously frozen ground carbon accessible to microorganisms, which break it down and release it as carbon dioxide and methane. The greenhouse gas release amplifies global warming, which is known as permafrost-carbon feedback.

There are still many unknowns concerning the amount of future greenhouse gas emissions. It is unknown, for example, how well ancient carbon that has been frozen in permafrost for thousands of years can be degraded. To find out, the researchers collected carbon dioxide samples at the Siberian inquiry site on the Lena River using specially built equipment that allows carbon dioxide to be held airtight and transported for lengthy periods of time.

This is required due to the long journey to Germany. Back in Cologne, the researchers used the radiocarbon method to establish the age of the carbon dioxide. They also looked at non-radioactive carbon isotopes. Both factors were then used to compute the amount of old and young carbon, as well as organic and inorganic carbon, that had decomposed in the thawing permafrost.

A significant percentage of the carbon, up to 80%, comes from ancient biological stuff that was freeze-locked into the sediments more than 30,000 years ago. This means that vegetative remains from thousands of years ago have been exceptionally well ‘preserved’ in the frozen silt, making them an appealing food supply for microbes in the thawing permafrost.

Furthermore, scientists discovered for the first time that up to 18% of carbon dioxide comes from inorganic sources. ‘We did not expect that this hitherto undiscovered carbon source would account for such a large fraction of the total amount of greenhouse gases released,’ said Jan Melchert of the University of Cologne, the study’s first author. This source would have to be considered for more accurate climate projections. Future research will need to determine where the inorganic carbon in the yedoma comes from and how it is released.

New research indicates that as the globe heats, carbon will escape faster. Researchers now predict that permafrost may release the equivalent of four to six years’ worth of coal, oil, and natural gas emissions for every one degree Celsius rise in Earth’s average temperature—double to triple what experts thought just a few years ago. If we don’t reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, permafrost might become as significant a producer of greenhouse gases as China, the world’s top emitter, is now within a few decades.