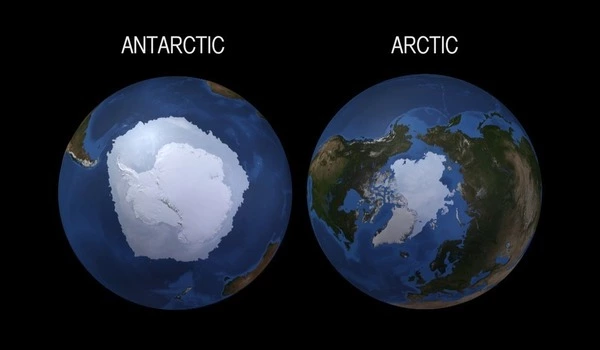

The loss of 3000+ billion tons of ice from the Antarctic Ice Sheet over 25 years is a significant and concerning trend that indicates the ongoing impact of climate change on our planet. This loss of ice can have far-reaching consequences, including rising sea levels and changes in ocean currents that can impact the global climate system.

Scientists estimate that over a 25-year period, the Amundsen Sea Embayment has lost more than 3,000 billion tonnes of ice. If all of the lost ice was piled on London, it would be over 2 km tall, or 7.4 times the height of the Shard. If it were to cover Manhattan, it would be 61 kilometers long, or 137 Empire State Buildings stacked on top of one another.

Twenty major glaciers form the Amundsen Sea Embayment in West Antarctica, which is more than four times the size of the United Kingdom, and they play an important role in contributing to global ocean levels. So much water is held in the snow and ice, that if it were to all to drain into the sea, global sea levels could increase by more than one metre.

Dr. Benjamin Davison of the University of Leeds led the study, which calculated the “mass balance” of the Amundsen Sea Embayment. This term refers to the balance of snow and ice gain due to snowfall and mass loss due to calving, which occurs when icebergs form at the end of a glacier and drift out to sea.

The 20 glaciers in West Antarctica have lost an awful lot of ice over the last quarter-century and there is no sign that the process is going to reverse anytime soon. Scientists are monitoring what is happening in the Amundsen Sea Embayment because of the crucial role it plays in sea-level rise.

Dr. Davison

When calving occurs faster than snowfall replaces the ice, the Embayment loses mass overall and contributes to global sea level rise. Similarly, if the supply of snowfall falls, the Embayment may lose mass overall, contributing to sea level rise.

According to the findings, West Antarctica experienced a net loss of 3,331 billion tonnes of ice between 1996 and 2021, contributing more than nine millimetres to global sea levels. The most important factors driving ice loss are thought to be changes in ocean temperature and currents.

“The 20 glaciers in West Antarctica have lost an awful lot of ice over the last quarter-century and there is no sign that the process is going to reverse anytime soon,” said Dr Davison, a Research Fellow at the Institute for Climate and Atmospheric Science at the University of Leeds.

“Scientists are monitoring what is happening in the Amundsen Sea Embayment because of the crucial role it plays in sea-level rise. If ocean levels were to rise significantly in future years, there are communities around the world who would experience extreme flooding.”

The research has been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

Extreme snowfall events

The scientists discovered that the Amundsen Sea Embayment had experienced several extreme snowfall events over the 25-year study period by using climate models that show how air currents move around the world. These would have resulted in periods of heavy snowfall followed by periods of little snowfall, resulting in a “snow drought.”

These extreme events were taken into account by the researchers in their calculations. Surprisingly, they discovered that these events contributed up to half of the ice change at certain times, and thus played a key role in the Amundsen Sea Embayment’s contribution to sea level rise during certain time periods.

For example, between 2009 and 2013, the models revealed a period of a persistant snow drought. The lack of snowfall starved the ice sheet and caused it to lose ice, therefore contributing about 25% more to sea level rise than in years of average snowfall.

In contrast, during the winters of 2019 and 2020 there was very heavy snowfall. The scientists estimated that this heavy snowfall mitigated the sea level contribution from the Amundsen Sea Embayment, reducing it to about half of what it would have been in an average year.

Dr. Davison said: “Changes in ocean temperature and circulation appear to be driving the long-term, large-scale changes in West Antarctica ice sheet mass. We absolutely need to research those more because they are likely to control the overall sea level contribution from West Antarctica.

“However, we were really surprised to see how much periods of extremely low or high snowfall could affect the ice sheet over two to five-year periods – so much so that we believe they could play an important, albeit secondary, role in controlling rates of West Antarctic ice loss.”

“Ocean temperature changes and glacial dynamics appear strongly connected in this part of the world,” said Dr. Pierre Dutrieux, co-author of the study. “However, this work highlights the large variability and unexpected processes by which snowfall also plays a direct role in modulating glacier mass.”

New glacier named

The Pine Island Glacier, also known as PIG, has receded due to ice loss in the region over the last 25 years. As it receded, one of its tributary glaciers separated from the main glacier and accelerated rapidly. As a result, the UK Antarctic Place-names Committee has named the tributary glacier Piglet Glacier, so that future studies can locate and identify it without ambiguity.

Dr Anna Hogg, one of the authors of the paper and Associate Professor at the Institute of Climate and Atmospheric Science at Leeds, said: “As well as shedding new light on the role of extreme snowfall variability on ice sheet mass changes, this research also provides new estimates of how quickly this important region of Antarctica is contributing to sea level rise.”

“Satellite observations show that the newly named Piglet Glacier has increased its ice speed by 40%, while the larger PIG has receded to its smallest extent since records began.”

Satellites like the Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellite, which uses sensors that can “see” through cloud even during the long Polar night, have transformed our ability to monitor remote areas.

It is critical to have frequent measurements of ice speed and iceberg calving to monitor the incredibly rapid change occurring in Antarctica.