A new metric that compares earthquake-related fatalities to a country’s population size finds that Ecuador, Lebanon, Haiti, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Portugal have suffered the most from fatalities during the last five centuries.

Max Wyss and colleagues at the International Centre for Earth Simulation Foundation introduced a new impact measure in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America termed the earthquake fatality load, or EQFL. The EQFL of a specific earthquake is the ratio of earthquake fatalities to the estimated population for the country in the year of the earthquake.

In their study, Wyss, Michel Speiser, and Stavros Tolis calculate the earthquake fatality load for 35 countries and regions, by adding up the EQFL calculated for earthquakes in these countries occurring within roughly the past 500 years, as well as a measure of EQFL per year for each country. This last measure was used to rank the countries by the impact of earthquake fatalities.

We wanted to look at how serious it is to absorb those losses, for a country. When you do this quantitatively, the order of countries to worry about suddenly changes.

Max Wyss

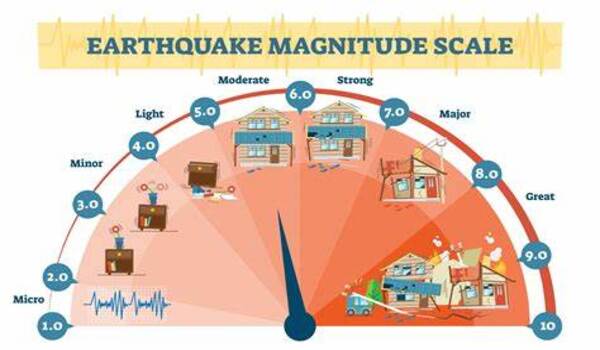

Between 1500 and March 2022, the countries in the study accounted for 97% of all earthquake-related fatalities. According to Wyss, the EQFL measurement eliminates deaths caused by earthquakes and tsunamis. Although major earthquakes in California, Japan, and China frequently make headlines due to their magnitude or property destruction, the goal of the EQFL measure, according to Wyss, was to show how the most critical impact of an earthquake, loss of life, affects some countries more than others.

“We wanted to look at how serious it is to absorb those losses, for a country,” he went on to say. “When you do this quantitatively, the order of countries to worry about suddenly changes.”

Smaller countries suffer more than larger countries from earthquake fatalities, even when they experience fewer fatal earthquakes, because the losses represent a larger proportion of their population, the researchers found.

They also noted that countries without major tectonic plate boundaries — boundaries where some of the Earth’s largest earthquakes occur — and countries with slow deformation accumulation rates on faults rank high in EQFL. For instance, the recent 2023 deadly earthquakes in Morocco and Afghanistan occurred along slowly deforming faults.

Wyss and colleagues also determined that the EQFL as a function of magnitude has dropped over time in all nations studied. According to the authors, structures have gotten more resistant to shaking over time, and countries have improved their ability to quickly provide relief to earthquake zones and rescue those trapped beneath rubble.

Global trends that show more people moving from villages to cities could also help to reduce EQFL, Wyss noted, because buildings in cities are more likely to be built with materials and designs that resist ground shaking, and emergency response can be faster in a city than in a remote village.

California, and a group of countries composed of Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico, had the strongest decrease in EQFL over the past 500 years. Italy had the least amount of EQFL decrease, “likely because old buildings are preserved, renovated and lived in,” the BSSA authors suggest.

Wyss has long called for a greater emphasis on earthquake deaths in order to better understand and mitigate the global consequences of earthquakes. He and his colleagues created QLARM (Quake Loss Assessment for Response and Mitigation), a tool that leverages global population and building stock data sets to provide a real-time computation of fatalities, injuries, and building damage caused by intense earthquake shaking. In the United States, the US Geological Survey’s PAGER (Prompt Assessment of Global Earthquakes for Response) instrument offers a comparable service.

People, not property, are the most important possible loss in an earthquake, according to Wyss, who adds that the chance of reducing fatalities using QLARM is what keeps him working without pay. “For that I’m willing to get out of bed when an earthquake happens at night for the rest of my life — as long as I’m still intelligent to do that — for people, not for money.”