According to the World Health Organization, overweight and obesity are among the most serious health issues of the twenty-first century (WHO). Furthermore, being overweight is frequently associated with severe secondary disorders such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, or heart attacks. Researchers have discovered which molecular mechanisms in obesity trigger secondary illnesses.

According to the World Health Organization, obesity and being overweight are among the most serious health issues of the twenty-first century (WHO). Almost 60% of Germans are considered overweight, with 25% being obese. Furthermore, being overweight is frequently associated with severe secondary disorders such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, or heart attacks.

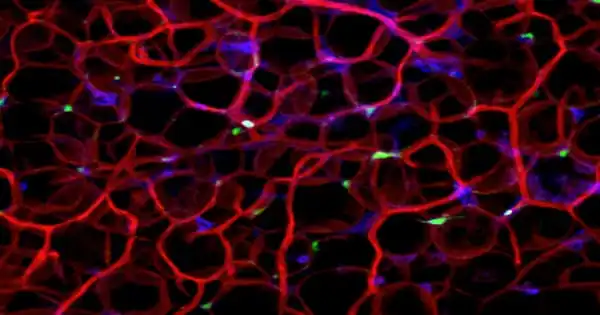

The size of fat tissue in the abdomen – or visceral adipose tissue, to be technical – is what physicians are concerned about. Strong expansion of this tissue is connected with an inflammatory immune response that spans the entire body, increasing the risk of secondary illnesses. Visceral adipose tissue is critical in these processes because immune cells can organize themselves into lymphoid structures and initiate immunological responses that disrupt the person’s metabolism.

The course of this disease is determined by immunological mechanisms. In a new study, a group of LMU researchers led by Dr. Susanne Stutte and Professor Barbara Walzog discovered that a high-calorie diet, even for just three weeks, has a significant impact on the immune system.

A type of immune cell known as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) begins to collect in visceral adipose tissue. These pDCs in visceral fat are now in a constant state of alarm and emit type I interferon.

Dr. Susanne Stutte

LMU researchers have now explored the molecular pathways that govern this so-called immunometabolism. They discovered that diet has a significant impact: “We find alterations in the molecular mechanisms that drive the immune system and metabolism in the organism after only three weeks of a high-fat, high-calorie diet,” explains Dr. Susanne Stutte, the main author of the study and researcher at the Biomedical Center Munich. Excess dietary energy is retained in adipose tissue, such as visceral fat, which is found in the abdomen and between the internal organs. Although everyone has this visceral fat, a high-calorie diet encourages it to expand and poses a health concern.

As visceral fat accumulates, immunological processes become unbalanced, as the researchers have shown: a kind of immune cell known as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) increases in visceral adipose tissue. “Tertiary lymphoid tissue begins to grow,” Stutte continues, “in which pDCs coordinate the immune system and influence metabolism.”

“A type of immune cell known as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) begins to collect in visceral adipose tissue,” Stutte adds. This adipose tissue is found inside the abdomen and protects internal organs. Small clusters of immune cells establish tertiary lymphoid structures inside this fat as a result of a high caloric diet, culminating in deadly immunological responses.

“These pDCs in visceral fat are now in a constant state of alarm and emit type I interferon,” Walzog adds. This interferon is normally used to fight infections, but in this case, it causes the metabolic syndrome by causing the metabolism to slow down and inflammatory markers to rise. When pDC migration into fat is inhibited, weight gain is prevented and metabolic status improves significantly.

“In the case of a viral infection, pDCs usually represent the first barrier, to which they respond by releasing a messenger (type-I interferon) that instructs the immune system,” explains Professor Barbara Walzog of LMU’s Walter Brendel Center of Experimental Medicine and Head of the Collaborative Research Center SFB 914 “Trafficking of Immune Cells in Inflammation, Development, and Disease.”

When inflammatory markers rise, the metabolism slows and the metabolic syndrome develops. “When the migration of pDCs into fat is stopped, weight gain is minimized and metabolic state improves,” Stutte says.

The study was conducted in partnership with Harvard Medical School, and the findings, according to the researchers, could help to the development of new techniques toward therapeutic intervention in metabolic illnesses. The migration of pDCs into adipose tissue follows precise molecular patterns, which can be thought of as maps. “If we could limit pDC migration into fat, for example, we might be able to prevent the resulting secondary disorders as well,” argues Walzog.

The findings of this study, which was conducted in partnership with Harvard Medical School in Boston, could now help to the development of novel approaches to metabolic syndrome therapeutic intervention.