A new small study done by Johns Hopkins Medicine experts and published in the journal Nature Cardiovascular Research reveals the influence of obesity on muscle structure in individuals with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

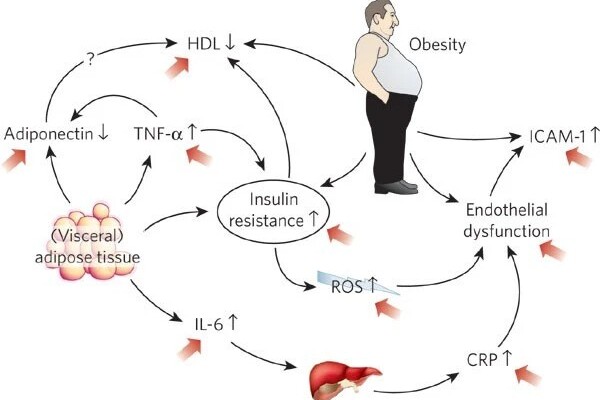

According to the Journal of Cardiac Failure, HFpEF accounts for more than 50% of all heart failure worldwide. Over 3.5 million cases of heart failure occur in the United States each year. Originally, this type of cardiac disease was connected with high blood pressure and excessive muscle growth (hypertrophy) to assist counteract the pressures. The Journal of the American College of Cardiology reports that HFpEF has become more common in people with extreme obesity and diabetes during the last two decades. However, there are still relatively few effective HFpEF medicines, and developing therapies has been hampered by a dearth of investigations in human heart tissue to understand precisely what is incorrect. As hospitalization and death rates in HFpEF patients are quite high, (30-40% over 5 years), understanding its underlying causes is critical.

“HFpEF is a complex syndrome, involving abnormalities in many different organs,” says lead investigator David Kass, M.D., Professor of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “We call it heart failure (HF) because its symptoms are similar to those found in patients with hearts that are weak. However, with HFpEF, heart contraction seems fine, yet heart failure symptoms still exist. While many prior efforts to treat HFpEF using standard HF drugs have not worked, success has since come from drugs used to treat diabetes and obesity.”

HFpEF is a complex syndrome, involving abnormalities in many different organs. We call it heart failure (HF) because its symptoms are similar to those found in patients with hearts that are weak. However, with HFpEF, heart contraction seems fine, yet heart failure symptoms still exist.

David Kass

More specifically, the medicine used to treat diabetes, known as an SGLT2 inhibitor (sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitor), is now the only evidence-based therapy for HFpEF that has improved not only symptoms but also lowered long-term rehospitalization rates and mortality outcomes. The weight loss medicine GLP1-receptor agonist has been studied and found to alleviate symptoms in people with HFpEF, and continuing trials are looking into whether a similar hard end-point (mortality reduction, hospitalization for HF reduction) is also attainable. As a result, these medications have already been demonstrated to be useful not just in diabetes, where they originated, but also in HFpEF.

To perform the study, the research team obtained a small piece of muscle tissue from 25 patients who had been diagnosed with varying degrees of HFpEF caused by diabetes and obesity and compared them to heart tissue from 14 organ donors whose hearts were considered to be normal. They examined the muscle using an electron microscope that shows muscle structure at a very high magnification.

Mariam Meddeb, M.D., MS, cardiovascular disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who conducted the study says, “Unlike viewing the heart with a traditional microscope, the electron microscope allows us to magnify the image to 40,000 times its size. This provides a very clear picture inside the muscle cell, what we call ultrastructure, such as mitochondria that are the energy power plants, and sarcomeres (unit of muscle fiber) that generate force.”

The researchers found notable ultrastructural abnormalities were particularly present in tissue of the most obese patients who had HEpEF, which had mitochondria that were swollen, pale, and disrupted, had many fat droplets, and their sarcomeres appeared tattered. These abnormalities were not related to whether the patient had diabetes, and were less prominent in patients who were less obese.

“These results will help those trying to develop animal models of HFpEF, since they show what one wants to generate at this microscopic level,” according to Dr. Kass. “It also raises the key question of whether reducing obesity, as is now being done with several drug therapies, will reverse these ultrastructural abnormalities, and in turn improve HFpEF outcome.”

The new findings advance our understanding of HFpEF, provide light on the role of obesity in heart disease, and present a target for medicines to enhance in order to benefit the many millions of HFpEF patients.