Linguists and historical linguists continue to explore and discuss the origins of the Indo-European languages. An international team of linguists and geneticists has made important advances in our understanding of the Indo-European language family, which is spoken by roughly half of the world’s population.

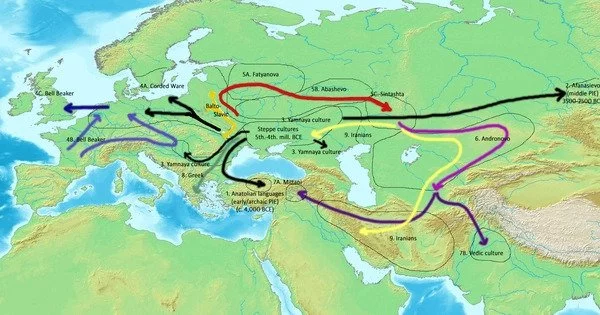

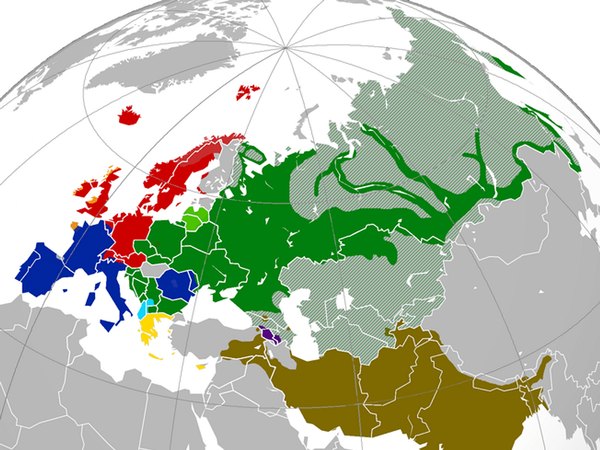

The origins of the Indo-European languages have been debated for almost two centuries. The ‘Steppe’ hypothesis, which posits a beginning in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe approximately 6000 years ago, and the ‘Anatolian’ or ‘farming’ hypothesis, which proposes an older origin connected to early agriculture around 9000 years ago, have recently dominated this argument. Previous evolutionary analyses of Indo-European languages reached contradictory findings about the family’s age, owing to flaws and inconsistencies in the datasets utilized, as well as restrictions in how phylogenetic algorithms analyzed ancient languages.

To address these issues, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology’s Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution assembled an international team of more than 80 language specialists to create a new dataset of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages, including 52 ancient or historical languages. This more complete and balanced sample, paired with strict processes for coding lexical data, corrected issues in prior studies’ datasets.

Ancient DNA and language phylogenetics thus combine to suggest that the resolution to the 200-year-old Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses.

Russell Grey

Indo-European estimated to be around 8100 years old

The researchers employed ancestry-enabled Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, which was recently established, to determine if historical written languages such as Classical Latin and Vedic Sanskrit were direct predecessors of modern Romance and Indic languages, respectively. Russell Grey, Head of the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution and the study’s senior author, emphasized the effort they took to ensure the study’s assumptions were sound. “Our chronology is robust across a wide range of alternative phylogenetic models and sensitivity analyses,” he explained. According to these findings, the Indo-European family is around 8100 years old, with five major branches having split off by around 7000 years ago.

These findings do not totally support either the Steppe or the agricultural hypothesis. “Recent ancient DNA data suggest that the Anatolian branch of Indo-European did not emerge from the Steppe, but from further south, in or near the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent – as the earliest source of the Indo-European family,” said Paul Heggarty, the study’s first author. Our language family tree structure and lineage split dates indicate that other early branches may have expanded directly from there, rather than through the Steppe.”

New insights from genetics and linguistics

The authors of the study therefore proposed a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages, with an ultimate homeland south of the Caucasus and a subsequent branch northwards onto the Steppe, as a secondary homeland for some branches of Indo-European entering Europe with the later Yamnaya and Corded Ware-associated expansions.

“Ancient DNA and language phylogenetics thus combine to suggest that the resolution to the 200-year-old Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses,” remarked Gray.

“Aside from a refined time estimate for the overall language tree, the tree topology and branching order are most critical for the alignment with key archaeological events and shifting ancestry patterns seen in the ancient human genome data,” says Wolfgang Haak, Group Leader in the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. This is a big step forward from the previously mutually exclusive alternatives towards a more credible model that incorporates archaeological, anthropological, and genetic discoveries.”