“Ambrose! Ambrose dear!” The new Mrs. Pottle put down the book she was reading Volume Dec to Erd of the encyclopedia.

“Yes, Blossom dear.” Mr. Pottle’s tone was fraught with the tender solicitude of the recently wed. He looked up from his book Volume Ode to Pay of the encyclopedia.

“Ambrose, we must get a dog!”

“A dog, darling?”

His tone was still tender but a thought lacking in warmth. His smile, he hoped, conveyed the impression that while he utterly approved of Blossom, herself, personally, her current idea struck no responsive chord in his bosom.

“Yes, a dog.”

She sighed as she gazed at a large framed steel-engraving of Landseer’s St. Bernards that occupied a space on the wall until recently tenanted by a crayon enlargement of her first husband in his lodge regalia.

“Such noble creatures,” she sighed. “So intelligent. And so loyal.”

“In the books they are,” murmured Mr. Pottle.

“Oh, Ambrose,” she protested with a pout. “How can you say such a thing? Just look at their big eyes, so full of soul. What magnificent animals! So full of understanding and fidelity and”

“Fleas?” suggested Mr. Pottle.

Her glance was glacial.

“Ambrose, you are positively cruel,” she said, tiny, injured tears gathering in her wide blue eyes. He was instantly penitent.

“Forgive me, dear,” he begged. “I forgot. In the books they don’t have them, do they? You see, precious, I don’t take as much stock in books as I used to. I’ve been fooled so often.”

“They’re lovely books,” said Mrs. Pottle, somewhat mollified. “You said yourself that you adore dog stories.”

“Sure I do, honey,” said Mr. Pottle, “but a man can like stories about elephants without wanting to own one, can’t he?”

“A dog is not an elephant, Ambrose.”

He could not deny it.

“Don’t you remember,” she pursued, rapturously, “that lovely book, ‘Hero, the Collie Beautiful,’ where a kiddie finds a puppy in an ash barrel, and takes care of it, and later the collie grows up and rescues the kiddie from a fire; or was that the book where the collie flew at the throat of the man who came to murder the kiddie’s father, and the father broke down and put his arms around the collie’s neck because he had kicked the collie once and the collie used to follow him around with big, hurt eyes and yet when he was in danger Hero saved him because collies are so sensitive and so loyal?”

“Uh huh,” assented Mr. Pottle.

“And that story we read, ‘Almost Human’,” she rippled on fluidly, “about the kiddie who was lost in a snow-storm in the mountains and the brave St. Bernard that came along with bottles of spirits around its neck St. Bernards always carry them and”

“Do the bottles come with the dogs?” asked Mr. Pottle, hopefully.

She elevated disapproving eyebrows.

“Ambrose,” she said, sternly, “don’t always be making jests about alcohol. It’s so common. You know when I married you, you promised never even to think of it again.”

“Yes, Blossom,” said Mr. Pottle, meekly.

She beamed.

“Well, dear, what kind of a dog shall we get?” she asked briskly. He felt that all was lost.

“There are dogs and dogs,” he said moodily. “And I don’t know anything about any of them.”

“I’ll read what it says here,” she said. Mrs. Pottle was pursuing culture through the encyclopedia, and felt that she would overtake it on almost any page now.

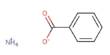

“Dog,” she read, “is the English generic term for the quadruped of the domesticated variety of canis.”

“Well, I’ll be darned!” exclaimed her husband. “Is that a fact?”

“Be serious, Ambrose, please. The choice of a dog is no jesting matter,” she rebuked him, and then read on, “In the Old and New Testaments the dog is spoken of almost with abhorrence; indeed, it ranks among the unclean beasts”

“There, Blossom,” cried Mr. Pottle, clutching at a straw, “what did I tell you? Would you fly in the face of the Good Book?”

She did not deign to reply verbally; she looked refrigerators at him.

“The Egyptians, on the other hand,” she read, a note of triumph in her voice, “venerated the dog, and when a dog died they shaved their heads as a badge of mourning”

“The Egyptians did, hey?” remarked Mr. Pottle, open disgust on his apple of face. “Shaved their own heads, did they? No wonder they all turned to mummies. You can’t tell me it’s safe for a man to shave his own head; there ought to be a law against it.”

Mr. Pottle was in the barber business.

Unheedful of this digression, Mrs. Pottle read on.

“There are many sorts of dogs. I’ll read the list so we can pick out ours. You needn’t look cranky, Ambrose; we’re going to have one. Let me see. Ah, yes. ‘There are Great Danes, mastiffs, collies, dalmatians, chows, New Foundlands, poodles, setters, pointers, retrievers Labrador and flat-coated spaniels, beagles, dachshunds I’ll admit they are rather nasty; they’re the only sort of dog I can’t bear whippets, otterhounds, terriers, including Scotch, Irish, Welsh, Skye and fox, and St. Bernards.’ St. Bernards, it says, are the largest; ‘their ears are small and their foreheads white and dome-shaped, giving them the well known expression of benignity and intelligence.’ Oh, Ambrose” her eyes were full of dreams “Oh, Ambrose, wouldn’t it be just too wonderful for words to have a great, big, beautiful dog like that?”

“There isn’t any too much room in this bungalow as it is,” demurred Mr. Pottle. “Better get a chow.”

“You don’t seem to realize, Ambrose Pottle,” the lady replied with some severity, “that what I want a dog for is protection.”

“Protection, my angel? Can’t I protect you?”

“Not when you’re away on the road selling your shaving cream. Then’s when I need some big, loyal creature to protect me.”

“From what?”

“Well, burglars.”

“Why should they come here?”

“How about all our wedding silver? And then kidnapers might come.”

“Kidnapers? What could they kidnap?”

“Me,” said Mrs. Pottle. “How would you like to come home from Zanesville or Bucyrus some day and find me gone, Ambrose?” Her lip quivered at the thought.

To Mr. Pottle, privately, this contingency seemed remote. His bride was not the sort of woman one might kidnap easily. She was a plentiful lady of a well developed maturity, whose clothes did not conceal her heroic mold, albeit they fitted her as tightly as if her modiste were a taxidermist. However, not for worlds would he have voiced this sacrilegious thought; he was in love; he preferred that she should think of herself as infinitely clinging and helpless; he fancied the rôle of sturdy oak.

“All right, Blossom,” he gave in, patting her cheek. “If my angel wants a dog, she shall have one. That reminds me, Charley Meacham, the boss barber of the Ohio House, has a nice litter. He offered me one or two or three if I wanted them. The mother is as fine a looking spotted coach dog as ever you laid an eye on and the pups”

“What was the father?” demanded Mrs. Pottle.

“How should I know? There’s a black pup, and a spotted pup, and a yellow pup, and a white pup and a”

Mrs. Pottle sniffed.

“No mungles for me,” she stated, flatly, “I hate mungles. I want a thoroughbred, or nothing. One with a pedigree, like that adorably handsome creature there.”

She nodded toward the engraving of the giant St. Bernards.

“But, darling,” objected Mr. Pottle, “pedigreed pups cost money. A dog can bark and bite whether he has a family tree or not, can’t he? We can’t afford one of these fancy, blue-blooded ones. I’ve got notes at the bank right now I don’t know how the dooce I’m going to pay. My shaving stick needs capital. I can’t be blowing in hard-earned dough on pups.”

“Oh, Ambrose, I actually believe you don’t care whether I’m kidnapped or not!” his wife began, a catch in her voice. A heart of wrought iron would have been melted by the pathos of her tone and face.

“There, there, honey,” said Mr. Pottle, hastily, with an appropriate amatory gesture, “you shall have your pup. But remember this, Blossom Pottle. He’s yours. You are to have all the responsibility and care of him.”

“Oh, Ambrose, you’re so good to me,” she breathed.

The next evening when Mr. Pottle came home he observed something brown and fuzzy nestling in his Sunday velour hat. With a smothered exclamation of the kind that has no place in a romance, he dumped the thing out and saw it waddle away on unsteady legs, leaving him sadly contemplating the strawberry silk lining of his best hat.

“Isn’t he a love? Isn’t he just too sweet,” cried Mrs. Pottle, emerging from the living room and catching the object up in her arms. “Come to mama, sweetie-pie. Did the nassy man frighten my precious Pershing?”

“Your precious what?”

“Pershing. I named him for a brave man and a fighter. I just know he’ll be worthy of it, when he grows up, and starts to protect me.”

“In how many years?” inquired Mr. Pottle, cynically.

“The man said he’d be big enough to be a watch dog in a very few months; they grow so fast.”

“What man said this?”

“The kennel man. I bought Pershing at the Laddiebrook-Sunshine Kennels to-day.” She paused to kiss the pink muzzle of the little animal; Mr. Pottle winced at this but she noted it not, and rushed on.

“Such an interesting place, Ambrose. Nothing but dogs and dogs and dogs. All kinds, too. They even had one mean, sneaky-looking dachshund there; I just couldn’t trust a dog like that. Ugh! Well, I looked at all the dogs. The minute I saw Pershing I knew he was my dog. His little eyes looked up at me as much as to say, ‘I’ll be yours, mistress, faithful to the death,’ and he put out the dearest little pink tongue and licked my hand. The kennel man said, ‘Now ain’t that wonderful, lady, the way he’s taken to you? Usually he growls at strangers. He’s a one man dog, all right, all right’.”

“A one man dog?” said Mr. Pottle, blankly.

“Yes. One that loves his owner, and nobody else. That’s just the kind I want.”

“Where do I come in?” inquired Mr. Pottle.

“Oh, he’ll learn to tolerate you, I guess,” she reassured him. Then she rippled on, “I just had to have him then. He was one of five, but he already had a little personality all his own, although he’s only three weeks old. I saw his mother a magnificent creature, Ambrose, big as a Shetland pony and twice as shaggy, and with the most wonderful appealing eyes, that looked at me as if it stabbed her to the heart to have her little ones taken from her. And such a pedigree! It covers pages. Her name is Gloria Audacious Indomitable; the Audacious Indomitables are a very celebrated family of St. Bernards, the kennel man said.”

“What about his father?” queried Mr. Pottle, poking the ball of pup with his finger.

“I didn’t see him,” admitted Mrs. Pottle. “I believe they are not living together now.”

She snuggled the pup to her capacious bosom.

“So,” she said, “its whole name is Pershing Audacious Indomitable, isn’t it, tweetums?”

“It’s a swell name,” admitted Mr. Pottle. “Er Blossom dear, how much did he cost?”

She brought out the reply quickly, almost timidly.

“Fifty dollars.”

“Fif” his voice stuck in his larynx. “Great Cæsar’s Ghost!”

“But think of his pedigree,” cried his wife.

All he could say was:

“Great Cæsar’s Ghost! Fifty dollars! Great Cæsar’s Ghost!”

“Why, we can exhibit him at bench shows,” she argued, “and win hundreds of dollars in prizes. And his pups will be worth fifty dollars per pup easily, with that pedigree.”

“Great Cæsar’s Ghost,” said Mr. Pottle, despondently. “Fifty dollars! And the shaving stick business all geflooey.”

“He’ll be worth a thousand to me as a protector,” she declared, defiantly. “You wait and see, Ambrose Pottle. Wait till he grows up to be a great, big, handsome, intelligent dog, winning prizes and protecting your wife. He’ll be the best investment we ever made, you mark my words.”

Had Pershing encountered Mr. Pottle’s eye at that moment the marrow of his small canine bones would have congealed.

“All right, Blossom,” said her spouse, gloomily. “He’s yours. You take care of him. I wonder, I just wonder, that’s all.”

“What do you wonder, Ambrose?”

“If they’ll let him visit us when we’re in the poor house.”

To this his wife remarked, “Fiddlesticks,” and began to feed Pershing from a nursing bottle.

“Grade A milk, I suppose,” groaned Mr. Pottle.

“Cream,” she corrected, calmly. “Pershing is no mungle. Remember that, Ambrose Pottle.”

It was a nippy, frosty night, and Mr. Pottle, after much chattering of teeth, had succeeded in getting a place warm in the family bed, and was floating peacefully into a dream in which he got a contract for ten carload lots of Pottle’s Edible Shaving Cream. “Just Lather, Shave and Lick. That’s All,” when his wife’s soft knuckles prodded him in the ribs.

“Ambrose, Ambrose, do wake up. Do you hear that?”

He sleepily opened a protesting eye. He heard faint, plaintive, peeping sounds somewhere in the house.

“It’s that wretched hound,” he said crossly.

“Pershing is not a hound, Ambrose Pottle.”

“Oh, all right, Blossom, All Right. It’s that noble creature, G’night.”

But the knuckles tattooed on his drowsy ribs again.

“Ambrose, he’s lonesome.”

No response.

“Ambrose, little Pershing is lonesome.”

“Well, suppose you go and sing him to sleep.”

“Ambrose! And us married only a month!”

Mr. Pottle sat up in bed.

“Is he your pup,” he demanded, oratorically, “or is he not your pup, Mrs. Pottle? And anyhow, why pamper him? He’s all right. Didn’t I walk six blocks in the cold to a grocery store to get a box for his bed? Didn’t you line it with some of my best towels? Isn’t it under a nice, warm stove? What more can a hound”

“Ambrose!”

“noble creature, expect?”

He dived into his pillow as if it were oblivion.

“Ambrose,” said his wife, loudly and firmly, “Pershing is lonesome. Thoroughbreds have such sensitive natures. If he thought we were lying here neglecting him, it wouldn’t surprise me a bit if he died of a broken heart before morning. A pedigreed dog like Pershing has the feelings of a delicate child.”

Muffled words came from the Pottle pillow.

“Well, whose one man dog is he?”

Mrs. Pottle began to sniffle audibly.

“I don’t believe you’d care if I got up and c-caught my death of cold,” she said. “You know how easily I chill, too. But I c-can’t leave that poor motherless little fellow cry his heart out in that big, dark, lonely kitchen. I’ll just have to get up and”

She stirred around as if she really intended to. The chivalrous Mr. Pottle heaved up from his pillow like an irate grampus from the depths of a tank.

“I’ll go,” he grumbled, fumbling around with goose-fleshed limbs for his chilly slippers. “Shall I tell him about Little Red Riding Hood or Goody Two Shoes?”

“Ambrose, if you speak roughly to Pershing, I shall never forgive you. And he won’t either. No. Bring him in here.”

“Here?” His tone was aghast; barbers are aseptic souls.

“Yes, of course.”

“In bed?”

“Certainly.”

“Oh, Blossom!”

“We can’t leave him in the cold, can we?”

“But, Blossom, suppose he’s suppose he has”

The hiatus was expressive.

“He hasn’t.” Her voice was one of indignant denial. “Pedigreed dogs don’t. Why, the kennels were immaculate.”

“Humph,” said Mr. Pottle dubiously. He strode into the kitchen and returned with Pershing in his arms; he plumped the small, bushy, whining animal in bed beside his wife.

“I suppose, Mrs. Pottle,” he said, “that you are prepared to take the consequences.”

She stroked the squirming thing, which emitted small, protesting bleats.

“Don’t you mind the nassy man, sweetie-pie,” she cooed. “Casting ‘spersions on poor li’l lonesome doggie.” Then, to her husband, “Ambrose, how can you suggest such a thing? Don’t stand there in the cold.”

“Nevertheless,” said Mr. Pottle, oracularly, as he prepared to seek slumber at a point as remote as possible in the bed from Pershing, “I’ll bet a dollar to a doughnut that I’m right.”

Mr. Pottle won his doughnut. At three o’clock in the morning, with the mercury flirting with the freezing mark, he suddenly surged up from his pillow, made twitching motions with limbs and shoulders, and stalked out into the living room, where he finished the night on a hard-boiled army cot, used for guests.

As the days hurried by, he had to admit that the kennel man’s predictions about the rapid growth of the animal seemed likely of fulfillment. In a very few weeks the offspring of Gloria Audacious Indomitable had attained prodigious proportions.

“But, Blossom,” said Mr. Pottle, eyeing the animal as it gnawed industriously at the golden oak legs of the player piano, “isn’t he growing in a sort of funny way?”

“Funny way, Ambrose?”

“Yes, dear; funny way. Look at his legs.”

She contemplated those members.

“Well?”

“They’re kinda brief, aren’t they, Blossom?”

“Naturally. He’s no giraffe, Ambrose. Young thoroughbreds have small legs. Just like babies.”

“But he seems so sorta long in proportion to his legs,” said Mr. Pottle, critically. “He gets to look more like an overgrown caterpillar every day.”

“You said yourself, Ambrose, that you know nothing about dogs,” his wife reminded him. “The legs always develop last. Give Pershing a chance to get his growth; then you’ll see.”

Mr. Pottle shrugged, unconvinced.

“It’s time to take Pershing out for his airing,” Mrs. Pottle observed.

A fretwork of displeasure appeared on the normally bland brow of Mr. Pottle.

“Lotta good that does,” he grunted. “Besides, I’m getting tired of leading him around on a string. He’s so darn funny looking; the boys are beginning to kid me about him.”

“Do you want me to go out,” asked Mrs. Pottle, “with this heavy cold?”

“Oh, all right,” said Mr. Pottle blackly.

“Now, Pershing precious, let mama put on your li’l blanket so you can go for a nice li’l walk with your papa.”

“I’m not his papa,” growled Mr. Pottle, rebelliously. “I’m no relation of his.”

However, the neighbors along Garden Avenue presently spied a short, rotund man, progressing with reluctant step along the street, in his hand a leathern leash at the end of which ambled a pup whose physique was the occasion of some discussion among the dog-fanciers who beheld it.

“Blossom,” said Mr. Pottle it was after Pershing had outgrown two boxes and a large wash-basket “you may say what you like but that dog of yours looks funny to me.”

“How can you say that?” she retorted. “Just look at that long heavy coat. Look at that big, handsome head. Look at those knowing eyes, as if he understood every word we’re saying.”

“But his legs, Blossom, his legs!”

“They are a wee, tiny bit short,” she confessed. “But he’s still in his infancy. Perhaps we don’t feed him often enough.”

“No?” said Mr. Pottle with a rising inflection which had the perfume of sarcasm about it, “No? I suppose seven times a day, including once in the middle of the night isn’t often enough?”

“Honestly, Ambrose, you’d think you were an early Christian martyr being devoured by tigers to hear all the fuss you make about getting up just once for five or ten minutes in the night to feed poor, hungry little Pershing.”

“It hardly seems worth it,” remarked Mr. Pottle, “with him turning out this way.”

“What way?”

“Bandy-legged.”

“St. Bernards,” she said with dignity, “do not run to legs. Mungles may be all leggy, but not full blooded St. Bernards. He’s a baby, remember that, Ambrose Pottle.”

“He eats more than a full grown farm hand,” said Mr. Pottle. “And steak at fifty cents a pound!”

“You can’t bring up a delicate dog like Pershing on liver,” said Mrs. Pottle, crushingly. “Now run along, Ambrose, and take him for a good airing, while I get his evening broth ready.”

“They extended that note of mine at the Bank, Blossom,” said Mr. Pottle.

“Don’t let him eat out of ash cans, and don’t let him associate with mungles,” said Mrs. Pottle.

Mr. Pottle skulked along side-streets, now dragging, now being dragged by the muscular Pershing. It was Mr. Pottle’s idea to escape the attention of his friends, of whom there were many in Granville, and who, of late, had shown a disposition to make remarks about his evening promenade that irked his proud spirit. But, as he rounded the corner of Cottage Row, he encountered Charlie Meacham, tonsorialist, dog-fancier, wit.

“Evening, Ambrose.”

“Evening, Charlie.”

Mr. Pottle tried to ignore Pershing, to pretend that there was no connection between them, but Pershing reared up on stumpy hind legs and sought to embrace Mr. Meacham.

“Where’d you get the pooch?” inquired Mr. Meacham, with some interest.

“Wife’s,” said Mr. Pottle, briefly.

“Where’d she find it?”

“Didn’t find him. Bought him at Laddiebrook-Sunshine Kennels.”

“Oho,” whistled Mr. Meacham.

“Pedigreed,” confided Mr. Pottle.

“You don’t tell me!”

“Yep. Name’s Pershing.”

“Name’s what?”

“Pershing. In honor of the great general.”

Mr. Meacham leaned against a convenient lamp-post; he seemed of a sudden overcome by some powerful emotion.

“What’s the joke?” asked Mr. Pottle.

“Pershing!” Mr. Meacham was just able to get out. “Oh, me, oh my. That’s rich. That’s a scream.”

“Pershing,” said Mr. Pottle, stoutly, “Audacious Indomitable. You ought to see his pedigree.”

“I’d like to,” said Mr. Meacham, “I certainly would like to.”

He was studying the architecture of Pershing with the cool appraising eye of the expert. His eye rested for a long time on the short legs and long body.

“Pottle,” he said, thoughtfully, “haven’t they got a dachshund up at those there kennels?”

Mr. Pottle knitted perplexed brows.

“I believe they have,” he said. “Why?”

“Oh, nothing,” replied Mr. Meacham, struggling to keep a grip on his emotions which threatened to choke him, “Oh, nothing.” And he went off, with Mr. Pottle staring at his shoulder blades which titillated oddly as Mr. Meacham walked.

Mr. Pottle, after a series of tugs-of-war, got his charge home. A worry wormed its way into his brain like an auger into a pine plank. The worry became a suspicion. The suspicion became a horrid certainty. Gallant man that he was, and lover, he did not mention it to Blossom.

But after that the evening excursion with Pershing became his cross and his wormwood. He pleaded to be allowed to take Pershing out after dark; Blossom wouldn’t hear of it; the night air might injure his pedigreed lungs. In vain did he offer to hire a man at no matter what cost to take his place as companion to the creature which daily grew more pronounced and remarkable as to shape. Blossom declared that she would entrust no stranger with her dog; a Pottle, and a Pottle only, could escort him. The nightly pilgrimage became almost unendurable after a total stranger, said to be a Dubuque traveling man, stopped Mr. Pottle on the street one evening and asked, gravely:

“I beg pardon, sir, but isn’t that animal a peagle?”

“He is not a beagle,” said Mr. Pottle, shortly.

“I didn’t say ‘beagle’,” the stranger smiled, “I said ‘peagle’ p-e-a-g-l-e.”

“What’s that?”

“A peagle,” answered the stranger, “is a cross between a pony and a beagle.” It took three men to stop the fight.

Pershing, as Mr. Pottle perceived all too plainly, was growing more curious and ludicrous to the eye every day. He had the enormous head, the heavy body, the shaggy coat, and the benign, intellectual face of his mother; but alas, he had the bandy, caster-like legs of his putative father. He was an anti-climax. Everybody in Granville, save Blossom alone, seemed to realize the stark, the awful truth about Pershing’s ancestry. Even he seemed to realize his own sad state; he wore a shamefaced look as he trotted by the side of Ambrose Pottle; Mr. Pottle’s own features grew hang-dog. Despite her spouse’s hints, Blossom never lost faith in Pershing.

“Just you wait, Ambrose,” she said. “One of these fine days you’ll wake up and find he has developed a full grown set of limbs.”

“Like a tadpole, I suppose,” he said grimly.

“Joke all you like, Ambrose. But mark my words: you’ll be proud of Pershing. Just look at him there, taking in every word we say. Why, already he can do everything but speak. I just know I could count on him if I was in danger from burglars or kidnapers or anything. I’ll feel so much safer with him in the house when you take your trip East next month.”

“The burglar that came on him in the dark would be scared to death,” mumbled Mr. Pottle. She ignored this aside.

“Now, Ambrose,” she said, “take the comb and give him a good combing. I may enter him in a bench show next month.”

“You ought to,” remarked Mr. Pottle, as he led Pershing away, “he looks like a bench.”

It was with a distinct sense of escape that Mr. Pottle some weeks later took a train for Washington where he hoped to have patented and trade-marked his edible shaving cream, a discovery he confidently expected to make his fortune.

“Good-by, Ambrose,” said Mrs. Pottle. “I’ll write you every day how Pershing is getting along. At the rate he’s growing you won’t know him when you come back. You needn’t worry about me. My one man dog will guard me, won’t you, sweetie-pie? There now, give your paw to Papa Pottle.”

“I’m not his papa, I tell you,” cried Mr. Pottle with some passion as he grabbed up his suit-case and crunched down the gravel path.

In all, his business in Washington kept him away from his home for twenty-four days. While he missed the society of Blossom, somehow he experienced a delicious feeling of freedom from care, shame and responsibility as he took his evening stroll about the capital. His trip was a success; the patent was secured, the trade-mark duly registered. The patent lawyer, as he pocketed his fee, perhaps to salve his conscience for its size, produced from behind a law book a bottle of an ancient and once honorable fluid and pressed it on Mr. Pottle.

“I promised the wife I’d stay on the sprinkling cart,” demurred Mr. Pottle.

“Oh, take it along,” urged the patent lawyer. “You may need it for a cold one of these days.”

It occurred to Mr. Pottle that if there is one place in the world a man may catch his death of cold it is on a draughty railroad train, and wouldn’t it be foolish of him with a fortune in his grasp, so to speak, not to take every precaution against a possibly fatal illness? Besides he knew that Blossom would never permit him to bring the bottle into their home. He preserved it in the only way possible under the circumstances. When the train reached Granville just after midnight, Mr. Pottle skipped blithely from the car, made a sweeping bow to a milk can, cocked his derby over his eye, which was uncommonly bright and playful, and started for home with the meticulous but precarious step of the tight-rope walker.

It was his plan, carefully conceived, to steal softly as thistledown falling on velvet, into his bungalow without waking the sleeping Blossom, to spend the night on the guest cot, to spring up, fresh as a dewy daisy in the morn, and wake his wife with a smiling and coherent account of his trip.

Very quietly he tip-toed along the lawn leading to his front door, his latch key out and ready. But as he was about to place a noiseless foot on his porch, something vast, low and dark barred his path, and a bass and hostile growl brought him to an abrupt halt.

“Well, well, well, if it isn’t li’l Pershin’,” said Mr. Pottle, pleasantly, but remembering to pitch his voice in a low key. “Waiting on the porch to welcome Papa Pottle home! Nice li’l Pershin’.”

“Grrrrrrr Grrrrrrrrrr Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr,” replied Pershing. He continued to bar the path, to growl ominously, to bare strong white teeth in the moonlight. In Mr. Pottle’s absence he had grown enormously in head and body; but not in leg.

“Pershin’,” said Mr. Pottle, plaintively, “can it be that you have forgotten Papa Pottle? Have you forgotten nice, kind mans that took you for pretty walks? That fed you pretty steaks? That gave you pretty baths? Nice li’l Pershin’, nice li’l”

Mr. Pottle reached down to pat the shaggy head and drew back his hand with something that would pass as a curse in any language; Pershing had given his finger a whole-hearted nip.

“You low-down, underslung brute,” rasped Mr. Pottle. “Get out of my way or I’ll kick the pedigree outa you.”

Pershing’s growl grew louder and more menacing. Mr. Pottle hesitated; he feared Blossom more than Pershing. He tried cajolery.

“Come, come, nice li’l St. Bernard. Great, big, noble St. Bernard. Come for li’l walk with Papa Pottle. Nice Pershin’, nice Pershin’, you dirty cur”

This last remark was due to the animal’s earnest but only partially successful effort to fasten its teeth in Mr. Pottle’s calf. Pershing gave out a sharp, disappointed yelp.

A white, shrouded figure appeared at the window.

“Burglar, go away,” it said, shrilly, “or I’ll sic my savage St. Bernard on you.”

“He’s already sicced, Blottom,” said a doleful voice. “It’s me, Blottom. Your Ambrose.”

“Why, Ambrose! How queer your voice sounds! Why don’t you come in.”

“Pershing won’t let me,” cried Mr. Pottle. “Call him in.”

“He won’t come,” she wailed, “and I’m afraid of him at night like this.”

“Coax him in.”

“He won’t coax.”

“Bribe him with food.”

“You can’t bribe a thoroughbred.”

Mr. Pottle put his hands on his hips, and standing in the exact center of his lawn, raised a high, sardonic voice.

“Oh, yes,” he said, “oh, dear me, yes, I’ll live to be proud of Pershing. Oh, yes indeed. I’ll live to love the noble creature. I’ll be glad I got up on cold nights to pour warm milk into his dear little stummick. Oh, yes. Oh, yes, he’ll be worth thousands to me. Here I go down to Washington, and work my head to the bone to keep a roof over us, and when I get back I can’t get under it. If you ask me, Mrs. Blottom Pottle née Gallup, if you ask me, that precious animal of yours, that noble creature is the muttiest mutt that ever”

“Ambrose!” Her edged voice clipped his oration short. “You’ve been drinking!”

“Well,” said Mr. Pottle in a bellowing voice, “I guess a hound like that is enough to drive a person to drink. G’night, Blottom. I’m going to sleep in the flower bed. Frozen petunias will be my pillow. When I’m dead and gone, be kind to little Pershing for my sake.”

“Ambrose! Stop. Think of the neighbors. Think of your health. Come into the house this minute.”

He tried to obey her frantic command, but the low-lying, far-flung bulk of Pershing blocked the way, a growling, fanged, hairy wall. Mr. Pottle retreated to the flower bed.

“What was it the Belgiums said?” he remarked. “They shall not pash.”

“Oh, what’ll I do, what’ll I do?” came from the window.

“Send for the militia,” suggested Mr. Pottle with savage facetiousness.

“I know,” cried his wife, inspired, “I’ll send for a veterinarian. He’ll know what to do.”

“A veterinarian!” he protested loudly. “Five bones a visit, and us the joke of Granville.”

But he could suggest nothing better and presently an automobile discharged a sleepy and disgusted dog-doctor at the Pottle homestead. It took the combined efforts of the two men and the woman to entice Pershing away from the door long enough for Mr. Pottle to slip into his house. During the course of Mrs. Pottle’s subsequent remarks, Mr. Pottle said a number of times that he was sorry he hadn’t stayed out among the petunias.

In the morning Pershing greeted him with an innocent expression.

“I hope, Mr. Pottle,” said his wife, as he sipped black coffee, “that you are now convinced what a splendid watch dog Pershing is.”

“I wish I had that fifty back again,” he answered. “The bank won’t give me another extension on that note, Blossom.”

She tossed a bit of bacon to Pershing who muffed it and retrieved it with only slight damage to the pink roses on the rug.

“I can’t stand this much longer, Blossom,” he burst out.

“What?”

“You used to love me.”

“I still do, Ambrose, despite all.”

“You conceal it well. That mutt takes all your time.”

“Mutt, Ambrose?”

“Mutt,” said Mr. Pottle.

“See! He’s heard you,” she cried. “Look at that hurt expression in his face.”

“Bah,” said Mr. Pottle. “When do we begin to get fifty dollars per pup. I could use the money. Isn’t it about time this great hulking creature did something to earn his keep? He’s got the appetite of a lion.”

“Don’t mind the nassy mans, Pershing. We’re not a mutt, are we, Pershing? Ambrose, please don’t say such things in his presence. It hurts him dreadfully. Mutt, indeed. Just look at those big, gentle, knowing eyes.”

“Look at those legs, woman,” said Mr. Pottle.

He despondently sipped his black coffee.

“Blossom,” he said. “I’m going to Chicago to-night. Got to have a conference with the men who are dickering with me about manufacturing my shaving cream. I’ll be gone three days and I’ll be busy every second.”

“Yes, Ambrose. Pershing will protect me.”

“And when I come back,” he went on sternly, “I want to be able to get into my own house, do you understand?”

“I warned you Pershing was a one man dog,” she replied. “You’d better come back at noon while he’s at lunch. You needn’t worry about us.”

“I shan’t worry about Pershing,” promised Mr. Pottle, reaching for his suit-case.

He had not overstated how busy he would be in Chicago. His second day was crowded. After a trip to the factory, he was closeted at his hotel in solemn conference in the evening with the president, a vice-president or two, a couple of assistant vice-presidents and their assistants, and a collection of sales engineers, publicity engineers, production engineers, personnel engineers, employment engineers, and just plain engineers; for a certain large corporation scented profit in his shaving cream. They were putting him through a business third degree and he was enjoying it. They had even reached the point where they were discussing his share in the profits if they decided to manufacture his discovery. Mr. Pottle was expatiating on its merits.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “there are some forty million beards every morning in these United States, and forty million breakfasts to be eaten by men in a hurry. Now, my shaving cream being edible, combines”

“Telegram for Mr. Puddle, Mr. Puddle, Mr. Puddle,” droned a bell hop, poking in a head.

“Excuse me, gentlemen,” said Mr. Pottle. He hoped they would think it an offer from a rival company. As he read the message his face grew white. Alarming words leaped from the yellow paper.

“Come home. Very serious accident. Blossom.”

That was all, but to the recently mated Mr. Pottle it was enough. He crumpled the message with quivering fingers.

“Sorry, gentlemen,” he said, trying to smile bravely. “Bad news from home. We’ll have to continue this discussion later.”

“You can just make the 10:10 train,” said one of the engineers, sympathetically. “Hard lines, old man.”

Granville’s lone, asthmatic taxi coughed up Mr. Pottle at the door of his house; it was dark; he did not dare look at the door-knob. His trembling hand twisted the key in the lock.

“Who’s that?” called a faint voice. It was Blossom’s. He thanked God she was still alive.

He was in her room in an instant, and had switched on the light. She lay in bed, her face, once rosy, now pale; her eyes, once placid, now red-lidded and tear-swollen. He bent over her with tremulous anxiety.

“Honey, what’s happened? Tell your Ambrose.”

She raised herself feebly in bed. He thanked God she could move.

“Oh, it’s too awful,” she said with a sob. “Too dreadful for words.”

“What? Oh, what? Tell me, Blossom dearest. Tell me. I’ll be brave, little woman. I’ll try to bear it.” He pressed her fevered hands in his.

“I can hardly believe it,” she sobbed. “I c-can hardly believe it.”

“Believe it? Believe what? Tell me, Blossom darling, in Heaven’s name, tell me.”

“Pershing,” she sobbed in a heart-broken crescendo, “Pershing has become a mother!”

Her sobs shook her.

“And they’re all mungles,” she cried, “all nine of them.”

Thunderclouds festooned the usually mild forehead of Mr. Pottle next morning. He was inclined to be sarcastic.

“Fifty dollars per pup, eh?” he said. “Fifty dollars per pup, eh?”

“Don’t, Ambrose,” his wife begged. “I can’t stand it. To think with eyes like that Pershing should deceive me.”

“Pershing?” snorted Mr. Pottle so violently the toast hopped from the toaster. “Pershing? Not now. Violet! Violet! Violet!”

Mrs. Pottle looked meek.

“The ash man said he’d take the pups away if I gave him two dollars,” she said.

“Give him five,” said Mr. Pottle, “and maybe he’ll take Violet, too.”

“I will not, Ambrose Pottle,” she returned. “I will not desert her now that she has gotten in trouble. How could she know, having been brought up so carefully? After all, dogs are only human.”

“You actually intend to keep that”

She did not allow him to pronounce the epithet that was forming on his lips, but checked it, with…

“Certainly I’ll keep her. She is still a one man dog. She can still protect me from kidnapers and burglars.”

He threw up his hands, a despairing gesture.

In the days that followed hard on the heels of Violet’s disgrace, Mr. Pottle had little time to think of dogs. More pressing cares weighed on him. The Chicago men, their enthusiasm cooling when no longer under the spell of Mr. Pottle’s arguments, wrote that they guessed that at this time, things being as they were, and under the circumstances, they were forced to regret that they could not make his shaving cream, but might at some later date be interested, and they were his very truly. The bank sent him a frank little message saying that it had no desire to go into the barber business, but that it might find that step necessary if Mr. Pottle did not step round rather soon with a little donation for the loan department.

It was thoughts of this cheerless nature that kept Mr. Pottle tossing uneasily in his share of the bed, and with wide-open, worried eyes doing sums on the moonlit ceiling. He waited the morrow with numb pessimism. For, though he had combed the town and borrowed every cent he could squeeze from friend or foe, though he had pawned his favorite case of razors, he was three hundred dollars short of the needed amount. Three hundred dollars is not much compared to all the money in the world, but to Mr. Pottle, on his bed of anxiety, it looked like the Great Wall of China.

He heard the town clock boom a faint two. It occurred to him that there was something singular, odd, about the silence. It took him minutes to decide what it was. Then he puzzled it out. Violet née Pershing was not barking. It was her invariable custom to make harrowing sounds at the moon from ten in the evening till dawn. He had learned to sleep through them, eventually. He pointed out to Blossom that a dog that barks all the time is a dooce of a watch-dog, and she pointed out to him that a dog that barks all the time thus advertising its presence and its ferocity, would be certain to scare off midnight prowlers. He wondered why Violet was so silent. The thought skipped through his brain that perhaps she had run away, or been poisoned, and in all his worry, he permitted himself a faint smile of hope. No, he thought, I was born unlucky. There must be another reason. It was borne into his brain cells what this reason must be.

Slipping from bed without disturbing the dormant Blossom, he crept on wary bare toes from the room and down stairs. Ever so faint chinking sounds came from the dining room. With infinite caution Mr. Pottle slid open the sliding door an inch. He caught his breath.

There, in a patch of moonlight, squatted the chunky figure of a masked man, and he was engaged in industriously wrapping up the Pottle silver in bits of cloth. Now and then he paused in his labors to pat caressingly the head of Violet who stood beside him watching with fascinated interest, and wagging a pleased tail. Mr. Pottle was clamped to his observation post by a freezing fear. The busy burglar did not see him, but Violet did, and pointing her bushel of bushy head at him, she let slip a deep “Grrrrrrrrrrr.” The burglar turned quickly, and a moonbeam rebounded from the polished steel of his revolver as he leveled it at a place where Mr. Pottle’s heart would have been if it had not at that precise second been in his throat, a quarter of an inch south of his Adam’s apple.

“Keep them up,” said the burglar, “or I’ll drill you like you was an oil-well.”

Mr. Pottle’s hands went up and his heart went down. The ultimate straw had been added; the wedding silver was neatly packed in the burglar’s bag. Mr. Pottle cast an appealing look at Violet and breathed a prayer that in his dire emergency her blue-blood would tell and she would fling herself with one last heroic fling at the throat of the robber. Violet returned his look with a stony stare, and licked the free hand of the thief.

A thought wave rippled over Mr. Pottle’s brain.

“You might as well take the dog with you, too,” he said.

“Your dog?” asked the burglar, gruffly.

“Whose else would it be?”

“Where’d you get her?”

“Raised her from a pup up.”

“From a pup up?”

“Yes, from a pup up.”

The robber appeared to be thinking.

“She’s some dog,” he remarked. “I never seen one just like her.”

For the first time in the existence of either of them, Mr. Pottle felt a faint glow of pride in Violet.

“She’s the only one of her kind in the world,” he said.

“I believe you,” said the burglar. “And I know a thing or two about dogs, too.”

“Really?” said Mr. Pottle, politely.

“Yes, I do,” said the burglar and a sad note had softened the gruffness of his voice. “I used to be a dog trainer.”

“You don’t tell me?” said Mr. Pottle.

“Yes,” said the burglar, with a touch of pride, “I had the swellest dog and pony act in big time vaudeville once.”

“Where is it now?” Mr. Pottle was interested.

“Mashed to bologny,” said the burglar, sadly. “Train wreck. Lost every single animal. Like that.” He snapped melancholy fingers to illustrate the sudden demise of his troupe. “That’s why I took to this,” he added. “I ain’t a regular crook. Honest. I just want to get together enough capital to start another show. Another job or two and I’ll have enough.”

Mr. Pottle looked his sympathy. The burglar was studying Violet with eyes that brightened visibly.

“If,” he said, slowly, “I only had a trick dog like her, I could start again. She’s the funniest looking hound I ever seen, bar none. I can just hear the audiences roaring with laughter.” He sighed reminiscently.

“Take her,” said Mr. Pottle, handsomely. “She’s yours.”

The burglar impaled him with the gimlet eye of suspicion.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “I could get away with a dog like that, couldn’t I? You couldn’t put the cops on my trail if I had a dog like that with me, oh, no. Why, I could just as easy get away with Pike’s Peak or a flock of Masonic Temples as with a dog as different looking as her. No, stranger, I wasn’t born yesterday.”

“I won’t have you pinched, I swear I won’t,” said Mr. Pottle earnestly. “Take her. She’s yours.”

The burglar resumed the pose of thinker.

“Look here, stranger,” he said at length. “Tell you what I’ll do. Just to make the whole thing fair and square and no questions asked, I’ll buy that dog from you.”

“You’ll what?” Mr. Pottle articulated.

“I’ll buy her,” repeated the burglar.

Mr. Pottle was incapable of replying.

“Well,” said the burglar, “will you take a hundred for her?”

Mr. Pottle could not get out a syllable.

“Two hundred, then?” said the burglar.

“Make it three hundred and she’s yours,” said Mr. Pottle.

“Sold!” said the burglar.

When morning came to Granville, Mr. Pottle waked his wife by gently, playfully, fanning her pink and white cheek with three bills of a large denomination.

“Blossom,” he said, and the smile of his early courting days had come back, “you were right. Violet was a one man dog. I just found the man.”

Written by Richard Connell