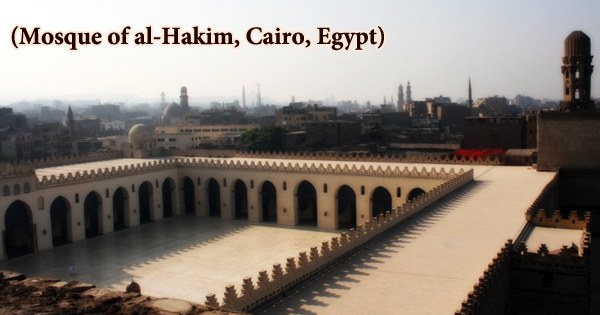

The Mosque of al-Hakim (Arabic: مسجد الحاكم بأمر الله, romanized: Masjid al-Ḥākim bi Amr Allāh), also known as al-Anwar (Arabic: الانور, lit. ’the Illuminated‘), is located at the start of al-Muizz li Din Allah Street, near to the Fatimid northern wall of Cairo’s Old City, only a few steps from Bab al-Futuh (Gate of Conquest) and Bab al-Nasr (Gate of Victory). It is named after Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (985–1021), the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili Imam, and it is an important Islamic holy monument in Cairo. The Fatimid Caliph al-‘Aziz began construction on the Mosque of al-Hakim in 990, and his son al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah and his overseer Abu Muhammad al-Hafiz ‘Abd al-Ghani ibn Sa’id al-Misri finished it in 1013.

Egypt is known for the kind and number of Islamic structures that have been created throughout history. When the Moslems first opened Egypt in 641 AD, they began erecting Islamic monuments. This Fatimid-style Mosque was constructed over a twenty-year period with a lot of community involvement. The enormous and starkly plain Mosque of Al Hakim, constructed inside Cairo’s northern fortifications in 1013, is one of the city’s earlier mosques, yet it was rarely used for worship. Instead, it served as a Crusader prison, a stable, a warehouse, a boys’ school, and, most appropriately, a madhouse, thanks to its infamous creator. The two stone minarets, the city’s oldest surviving structures, are the true masterpieces.

Al-Jamiʿ al-Anwar is another name for Al-Hakim Mosque. The minarets and stone facades of the mosque are made of brick. It has an irregular rectangular plan with a rectangular courtyard encircled by arcades supported by piers and a prayer hall with arcades supported by piers as well. The mosque of Al-Hakim is Egypt’s second largest Fatimid Mosque, and it is designed similarly to Ahmed Ibn Toulon’s Mosque. Al-Aziz Billah started its construction in the year 990, and the following Friday prayers were held there. The construction of Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah began in the year 1003 and was completed in Ramadan of the following year.

The Mosque was built at a cost of 40,000 dinars, with an additional 5,000 dinars spent on furnishings. Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah allowed a joyful parade to travel from al-Azhar to al-Anwar and back to al-Azhar at the time of the inauguration. With the exception of the two distinct minarets, the mosque was mostly constructed of brick. Stone was used to construct these structures. The mosque is composed of an open courtyard “Sahn” with four rooms “Riwaq” surrounding it from four directions, the largest and most beautiful of which is the Qibla Riwaq, which indicates the direction to Mecca that Moslems should face while praying.

Sultan Al Hakim, Egypt’s sixth Fatimid ruler, ascended to the throne at the age of 11 and was dubbed “Little Lizard” by his instructor due to his scary appearance and behavior. His 24-year rule was characterized by brutality and behavior that went far beyond the ordinary court intrigues, prompting subsequent historians to assume that he was just insane. He liked to travel to a cave in the Al Moqatem mountain and spend lengthy periods of time alone there. His death was as strange as his life; one night, while Al-Hakim was riding his donkey to his cave, he was assaulted and slain by a group of strong slaves, and his body was not discovered till now. This was the final event in the life of one of Egypt’s most powerful monarchs.

The mosque’s main (northwestern) façade runs parallel to al-Muizz Street. The mosque’s entrance is flanked by two squat towers that form a projecting grand doorway in the center of the façade. The mosque’s interior is an open courtyard surrounded by parallel columns that form a rectangle shape. Al Hakim ordered the minarets to be angled and the masjid columns to be exceedingly tall to cover the inside of the mosque in late 1010.

The width and height of the aisle leading to the mihrab are both highlighted. A dome carried on squinches marks the end of this aisle at the mihrab, and domes also mark the outside corners of the prayer hall. The portal is 15.50 m wide and 11 m high, and it projects 6 m from the façade. Recessed panels with bands of ornamental motifs and kufic inscriptions decorate the entry. The Fatimids introduced this decorative style to Egypt, which originated in North Africa and may be seen at the Great Mosque of Susa in Tunisia (AH 236 / AD 801).

The mosque’s vast white marble floor, which mirrors the mosque itself from inside, is the mosque’s second most stunning architectural feature. Birds come to the mosque, standing on its magnificent floor and drinking from the mosque’s fountain. The mosque used to have more than thirteen entrances, which is why there is an open space courtyard where anyone can enter from any direction. The two minarets at the two ends of the main façade are the work of al-Hakim bi-Amrillah, who had them built in AH 393 / AD 1002, after borrowing the concept of placing them at the two corners of the mosque façade from Tunisia’s Mahdiyya Great Mosque.

The third and most notable feature of Al-Hakim Mosque is its two distinctively designed minarets, which stand at the north and south corners of the western entrance. The two minarets used to be separate from the brick walls at the corners. These are the city’s oldest remaining minarets, which have been renovated several times throughout its history. Furthermore, due of the uncommon design that was transferred to Egypt from North Africa, the Fatimids’ homeland, no other minaret in Egypt like those of Al-Hakim Mosque.

During the reign of al-Hakim in 1002-3, the front facade was given a central projecting monumental doorway, and its two corner minarets, which were dissimilar in shape and design, were encased in projecting square stone structures. The Northern minaret is 33.7 meters long, with a cylindrical body and a “Mabkhra” style head above it, which was a popular design during the Fatimid era. The other minaret stands 24.7 meters tall, with an octagonal body above it and a “Mabkhra” head at the top.

Al-Hakim bi Amrillah constructed stone walls to the minarets eleven years after they were built, encasing the sides of the minarets and surrounding each of them along the exterior, giving them the appearance of towers. Inscription bands with Qur’anic passages written in the kufic script were included. The Kufic styles have changed through time as a result of many restorations. According to legend, the mosque had a total of twelve thousand feet of Kufic ornamentation. On all four sides of each of the five bays of the bayt-al-salat (House of Prayer) to the north and south of the Majāz, Kufic inscriptions may be found.

Because of its large size, the Al-Hakim Mosque was not always used as a mosque or a prayer location. It was utilized for a variety of various purposes throughout its history. There is also substantial architectural evidence that the mosque used to have three domes, one of which is still surviving. The arcades, arches, and domes of the mosque were constructed using bricks. The exterior walls, minarets, and projecting doorway, on the other hand, were built of stone.

The mosque’s floor plan, which is 120 m by 113 m, features a central open courtyard that measures 78 m by 66 m and is encircled by four porticoes. A name plate was etched on stone at the top of the entrance gate facing the inside of the Mosque. During renovation work, another marble name plate (picture) is set right below the main name plate, with information on the Mosque’s history and rehabilitation work.

Since the AH 9th / AD 15th century, the mosque has been neglected and deteriorated. During their battle against Egypt (AH 1213–16 / AD 1798–1801), the French utilized the mosque as a stronghold and the minarets as watchtowers. During Salah El Din’s reign, the Mosque of Al-Hakim served as a crusader prison and a horse stable, as well as a storage space for food and weapons during Napoleon Bona Parte’s French occupation of Egypt. The mosque was completely restored toward the end of the twentieth century.

Information Sources: