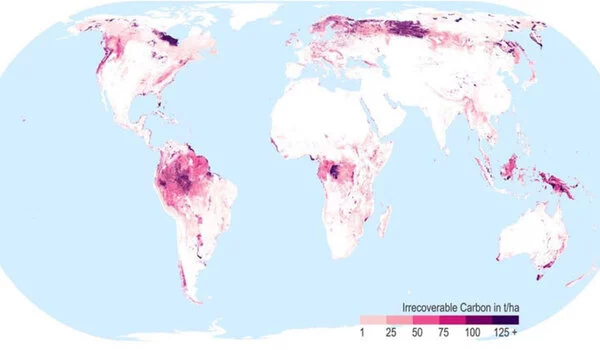

According to a recent study led by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, rising annual temperatures and decreasing annual precipitation across Central Asia’s mid-latitudes have extended its desert climate 60 miles northward since the 1980s.

According to a climate analysis of the region, what was once a semi-arid climate zone with at least some summer precipitation has since transitioned to a drier and hotter clime with little rainfall during the growing season. When comparing the 20-year period of 1960-1980 to the 30-year period of 1990-2020, the average annual temperature in the once-temperate areas rose by about 9 degrees Fahrenheit.

Central Asia is home to more than 70 million people and includes five former Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, but it is also thought to include Afghanistan, western China, and fragments of other neighboring countries. Because more than 60% of its land is in arid or semi-arid climate, the region is especially vulnerable to drought and sensitive to precipitation fluctuations, according to the researchers.

“Because the region is dry, small deviations from the average or anticipated amount of growing-season rainfall can be devastating to the region’s agricultural production and social stability,” said Qi “Steve” Hu, a Nebraska professor of natural resources and Earth and atmospheric sciences. “It’s a place that’s extremely vulnerable to climate change.”

Because the region is dry, small deviations from the average or anticipated amount of growing-season rainfall can be devastating to the region’s agricultural production and social stability. It’s a place that’s extremely vulnerable to climate change.

Prof. Qi Steve Hu

That vulnerability spurred Hu and Lanzhou University’s Zihang Han to examine Central Asia’s monthly air temperature and precipitation data, which stretches back to the mid-20th century. But unlike most prior studies, which analyzed variations in individual elements of climate, Hu and Han tied the region’s temperature and precipitation to its vegetation and ecology by instead assessing shifts in climate types, from tundra and temperate continental to subtropical and desert.

The researchers discovered that, as the latitudinal zones of desert climate expanded northward, an envelope of wetter, colder continental climate further north was spreading southward. That pincer movement has steepened the gradient of temperature and pressure disparities across latitudes by narrowing the distance between the two climates. According to Hu, the steeper gradient favors a clockwise rotation of the atmosphere, which in turn favors air sinking, essentially acting as a “cloud killer” that could lead to even less precipitation and a more severe desert climate.

All 11 of the identified climate types in Central Asia saw substantial increases in annual temperature from 1990 to 2020. Whereas most of those climates also experienced decreases in annual precipitation, the region’s high-altitude areas — among them, the Tianshan Mountains bordering China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan — have generally seen their precipitation increase. Combined with the simultaneous warming of those mountainous areas, a significant proportion of that extra precipitation — about 8 inches’ worth — has taken the form of rain rather than snow.

Temperature and precipitation increases are likely to have accelerated the melting of glaciers that once dominated mountainous landscapes, according to Hu. In the short term, an increase in meltwater is feeding rises in groundwater and bodies of surface water, including lakes, across western China’s Xinjiang Province and other mountainous areas. However, whatever short-term gains those areas may experience, he believes they will come at the expense of the more sustainable meltwater that the region’s mountains have provided for generations.

“That’s coming at the cost of your future water,” Hu said, adding that the risk of flash flooding will grow in the meantime. “If this continues, after maybe 20 or 30 more years, those glaciers and that snowpack could be gone. Then you have just the summer precipitation, which is not going to be enough to keep up the water level in your lakes and your soil to sustain agricultural production in the growing season.

“So you may be in a one-way drought from which you will not recover.” Though the situations are distinct, the projected uncertainty in Nebraska’s summer precipitation and the snowpack of the Rocky Mountains — snowpack that feeds the Platte River — should have Huskers thinking about the future of water in their own state, Hu said.

“This has some potential implications for the situation we’re facing in the west-central United States, particularly around the Rockies,” he said. “This could jeopardize the availability of water resources over the next 50 years.”