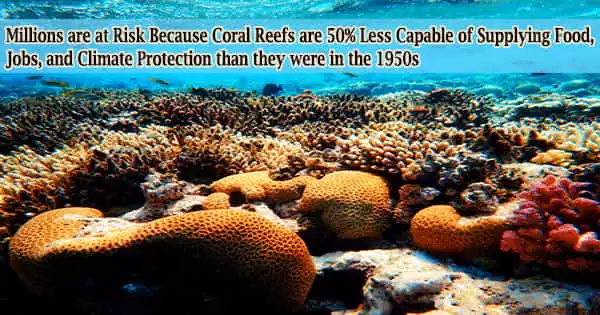

According to a recent study performed by the University of British Columbia, the ability of coral reefs to offer ecosystem services depended upon by millions of people globally has decreased by 50% since the 1950s.

The study provides the first thorough examination of the effects of climate change, overfishing, and habitat destruction on coral reefs’ ability to provide humans with important ecosystem services, such as food, livelihoods, and storm protection.

Overall, the results demonstrated that the coral reef’s capacity to deliver these services has suffered a similarly severe loss as a result of the significant loss in coral reef covering.

Other results are equally depressing: the scientists discovered that the diversity of species had decreased by more than 60% and that the global coverage of living corals had decreased by roughly 50% since the 1950s.

“It’s a call to action we’ve been hearing this time and time again from fisheries and biodiversity research,” said lead author Dr. Tyler Eddy, who conducted the research as a research associate at the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF).

Dr. Eddy, who is currently a research scientist at Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Fisheries & Marine Institute, claimed that the continued loss of healthy coral reefs and the habitat they provide is reducing the amount of ecosystem services available globally to the millions of people who depend on them.

“We know coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots. And preserving biodiversity not only protects nature but supports the humans that use these species for cultural, subsistence and livelihood means.”

This study speaks to the importance of how we manage coral reefs not only at regional scales, but also at the global scale, and the livelihoods of communities that rely on them.

Dr. William Cheung

The researchers combined datasets from surveys of coral reefs, estimated coral reef-associated biodiversity, fisheries catches and effort, impacts of fisheries on the structure of food webs, and Indigenous consumption of coral reef-associated fish to analyze trends for coral reef systems and associated ecosystems around the world. Additionally, they examined ecosystem service patterns at the regional, national, and international levels and contrasted them with trends for small island developing states.

The researchers discovered that catches of fish on coral reefs peaked in 2002 and have been slowly declining ever since, despite an increase in fishing effort, in addition to reductions in reef coverage and biodiversity. The catch per unit effort, which is frequently cited as a sign of changes in biomass, is 60% lower today than it was in 1950.

“This study speaks to the importance of how we manage coral reefs not only at regional scales, but also at the global scale, and the livelihoods of communities that rely on them,” said senior author Dr. William Cheung, professor, and director of IOF.

The researchers came to the conclusion that the well-being and sustainable development of coastal human settlements that depend on the coral reef are now in danger due to the continuous degradation of the reef in the years to come.

According to Dr. Eddy, fish and fisheries are an important source of essential micronutrients in coastal developing countries with few other options for food. Coral reef biodiversity and fisheries are especially important for Indigenous and coastal communities because they have strong cultural ties to the reefs and consume 15 times more seafood than non-Indigenous communities.

According to study co-author Dr. Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, who was an IOF research associate at the time of the study and is now an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University, the study shows how Indigenous and coastal communities, in this case those in the tropics, are unfairly suffering as a result of global actions.

“It’s heart-wrenching for us to see photos and video of wildfires or floods, and that level of destruction is happening right now all over the world’s coral reefs and threatening people’s culture, their daily food, and their history. This isn’t just an environmental issue, it’s also about human rights.”

“Finding targets for recovery and climate adaptation would require a global effort, while also addressing needs at a local level,” said Dr. Cheung.

“Climate mitigation actions, such as those highlighted in the Paris Agreement, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, all call for integrated action to address biodiversity, climate, and social challenges. We are not there yet.”