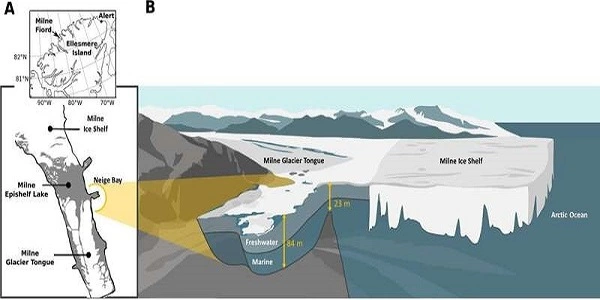

Investigators have produced an assessment of the abundance of the viruses in the Milne Fiord Epishelf Lake near the North Pole. Less than 500 miles from the North Pole, the Milne Fiord Epishelf Lake is a unique freshwater lake that floats atop the Arctic Ocean, held in place only by a coating of ice. The lake is dominated by single-celled organisms, notably cyanobacteria, that are frequently infected by unusual “giant viruses.” Investigators from Université Laval, Québec, Canada have produced the first assessment of the abundance of the viruses in this lake. The research is published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

Viruses are key to understanding polar aquatic ecosystems, as these ecosystems are dominated by single-celled microorganisms, which are frequently infected by viruses. These viruses, and their diversity and distribution in the Milne Fiord Lake have seldom been studied. The team is now working to sequence the giant viruses, an effort that will likely lead to understanding how the viruses influence the lake’s ecology via their interactions with the cyanobacteria they infect.

Quickly rising temperatures limit the time remaining to for microbiologists to develop a clear picture of the biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles of these ice-dependent environments, as well as the consequences of the rapid, irreversible changes in temperature. “The ice shelf that holds the lake in place is deteriorating every year, and when it breaks up, the lake will drain into the Arctic Ocean and be lost,” said corresponding author Alexander I. Culley.

Our results highlight the uniqueness of the viral community in the freshwater lake, as compared to the marine fiord water, particularly in the halocline community. The halocline is an area where salinity falls quickly as one ascends the water column. This environment offers niches for viruses and hosts which are found neither in freshwater nor marine layers of uniform salinity.

Alexander I. Culley

“Our results highlight the uniqueness of the viral community in the freshwater lake, as compared to the marine fiord water, particularly in the halocline community,” said Culley. The halocline is an area where salinity falls quickly as one ascends the water column. This environment offers niches for viruses and hosts which are found neither in freshwater nor marine layers of uniform salinity, he said.

The remote lake in the high arctic could only be reached by helicopter, when weather conditions allowed. The research team collected water samples and sequenced all the DNA in the lake water, allowing them to identify the viruses and microorganisms within it. The study establishes a basis for advancing understanding of viral ecology in diverse global environments, particularly in the high Arctic.

“High bacterial abundance coupled with a possible prevalence of lytic lifestyle at this depth suggests that viruses have an important role in biomass turnover,” said Mary Thaler, Ph.D., a member of Culley’s team at Université Laval. “Lytic lifestyle” refers to the release of daughter virus particles as the host microbial cell is destroyed.

The most dramatic change observed in the Milne Fiord Epishelf Lake was a multiyear decline in the abundance of cyanobacteria. The researchers attributed that drop to the increasing marine influence in the freshwater lake, “since cyanobacteria have very low abundance in the Arctic Ocean,” they wrote.

Nonetheless, the details of this ecosystem remain obscure, because so far most of its viruses are known only from fragments of their sequences. Thus, in most cases, the scientists do not yet know how the viruses influence the microbes they infect, or which viruses inhabit which microbes.