According to a recent multicenter study headed by Stanford Medicine clinicians and biomedical data scientists, breast cancer deaths decreased by 58% between 1975 and 2019 as a result of a combination of screening mammography and treatment advances.

Nearly one-third of the drop (29%) is attributed to breakthroughs in treating metastatic breast cancer, which is a type of cancer that has spread to other parts of the body and is classified as stage 4 or recurring cancer. Although these advanced tumors are not treatable, women with metastatic illness are enjoying longer lives than ever before. The study assists cancer researchers in determining where to spend future efforts and resources.

“We’ve known that breast cancer deaths have been declining for several decades, but it’s been difficult or impossible to quantify which of our interventions have been most successful and to what extent,” said Jennifer Caswell-Jin, MD, assistant professor of medicine. “This type of study allows us to see which of our efforts are having the most impact and where we still need to improve.”

Caswell-Jin and Liyang Sun are co-first authors of the study, which was published on January 16 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Co-senior authors include Sylvia Plevritis, PhD, professor and head of biological data science, and Allison Kurian, MD, MSc, professor of medicine, epidemiology, and public health.

We’ve known that breast cancer deaths have been declining for several decades, but it’s been difficult or impossible to quantify which of our interventions have been most successful and to what extent. This type of study allows us to see which of our efforts are having the most impact and where we still need to improve.

Jennifer Caswell-Jin

The study was carried out in collaboration with the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network, a nationwide partnership of researchers. The National Cancer Institute launched CISNET in 2000 to better investigate how cancer surveillance, screening, and treatment affect incidence and death. This requires sophisticated computer algorithms capable of modeling the natural course of the disease and the typical treatment paths of individual patients, which must then be translated to population-level data collected by the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, or SEER registry, from 1975 to 2019.

The study is the third in a trio of papers from CISNET published since 2005 that assess the relative contributions of regular screening and treatment advances on breast cancer deaths. The previous two papers informed national guidelines and helped cancer researchers focus their efforts on the most intractable problems.

“Twenty years ago, there was a question whether routine screening mammography actually decreased the number of deaths from breast cancer,” Plevritis said. But in 2005, she and other CISNET researchers published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine that conclusively demonstrated that screening was responsible for anywhere from 28% to 65% (different models came up with varying degrees of impact) of the reduction in mortality by 2000 between 1975 and 2000.

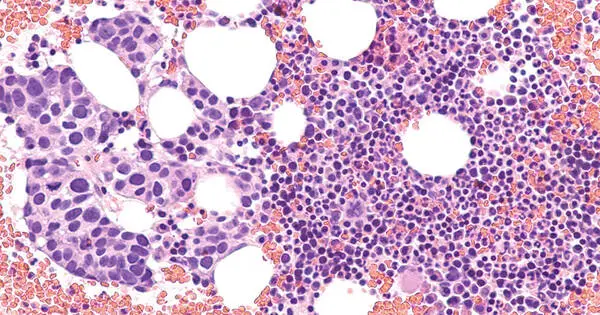

The second paper, published in 2018 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, highlighted the differences in treatment responsiveness and survival outcomes among women with differing breast cancer subtypes from 2000 to 2012 – pinpointing subgroups with poorer survival.

“We found that, while screening still had an important impact, most of the decline in annual deaths was due to improvements in treating early-stage breast cancer based on each cancer’s molecular profile,” Plevritis stated in a press release.

This is the first study that explicitly includes patients with metastatic breast cancer in its models. The researchers were astonished and pleased to learn that breakthroughs in treating metastatic breast cancer accounted for 29% of the drop in death.

“Initially, we assumed that treatment of advanced disease was unlikely to make a significant contribution to the declines in mortality we documented in the previous two papers,” Caswell-Jin said. “But our treatments have improved, and it’s clear that they are having a significant impact on annual mortality.”

The CISNET researchers used four computer models to assess the SEER data from 1975 to 2019 — one developed at Stanford Medicine in the Plevritis Lab, one by researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, one at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and another jointly developed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin and Harvard Medical School. The four models came up with remarkably similar estimates for the impact of each intervention: screening mammography, treatment of early-stage (stages 1, 2 or 3) breast cancer, and treatment of metastatic breast cancer.

The models reproduced the decline in mortality in breast cancer known from SEER data, from 48 per 100,000 women dying of breast cancer each year in 1975 to 27 per 100,000 in 2019 — a decrease of about 44%. The models arrived at a larger estimated reduction in mortality of about 58% because the incidence of breast cancer has risen during the same period and more women would have died had screening and treatments not improved.

The models concluded that about 47% of this reduction in mortality is the result of improved treatments for early-stage breast cancer, and about 25% is attributed to screening mammography. The remainder, or about 29%, is due to improvements in treating metastatic disease.

“Designing the new model, which had to account for individuals with non-metastatic cancer who underwent treatment but later progressed to metastatic cancer, and who may have been treated with multiple drugs over the course of their disease, was extremely complex,” Plevritis said in a press release. “It took almost four years. But it was quite exciting when we were able to evaluate the model’s behavior and observe that all four models from various institutions, each using the new model inputs in a unique way, produced consistent results. The models not only make sense but also provide useful insights.”

The benefit of treating metastatic cancer is shown by increases in median survival time following metastasis: patients diagnosed with metastatic disease in 2000 lived an average of 1.9 years, compared to an average of 3.2 years in 2019. However, survival time varies depending on the subgroup status. Patients with estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-positive malignancies had an average 2.5-year increase in survival time. Those with estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-negative malignancies lived an average of 1.6 years longer, whereas those with estrogen receptor-negative and HER2-negative tumors lived around 0.5 years longer in 2019 than in 2000.

“It was meaningful as a breast oncologist to spend time with this history and see real progress over the past decades,” she said. “There is still more work to be done; metastatic breast cancer is not yet treatable. But it’s encouraging to see that innovations have made a difference in these figures,” she said. “Our scientific and clinical work is helping our patients live longer, and I believe deaths from breast cancer will continue to steadily decline as innovation continues to grow.”