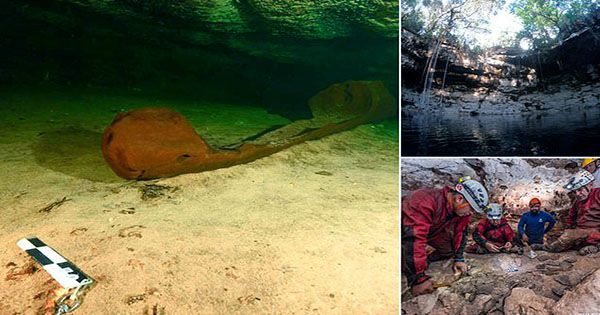

Dive archeologists have uncovered a stunningly preserved Maya boat deep beneath a water-filled sinkhole in Mexico, which is thought to be over 1,000 years old. A team from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) uncovered the 1.6-meter (5.2 foot) long, 80-centimeter (31.5 inch) broad canoe while excavating in the Mexican state of Yucatán.

The archeologists made the find while taking a break from their dive and peered into the limestone pool. One of the crewmembers discovered a black impression on the stonewall about 5 meters (16 feet) below the present water level, suggesting a previous water level. They discovered an antique watercraft in surprisingly good shape in a cave at this level.

The team speculates that the boat was either utilized to transfer water from the body of water or was left here as a ritual offering. The boat appears to date from the Maya Civilization’s Terminal Classic period (830-950 CE), but researchers plan to conduct a more extensive investigation later this year to provide a more exact dating and determine the sort of wood it was made of. A borehole of silt will be drilled beneath the canoe to learn more about how the watercraft got up here.

Sinkholes that have grown filled with water, known as cenotes, dot the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. They are produced when weather erodes the limestone bedrock and it collapses, exposing an underground hollow that eventually fills with water. They have a propensity of keeping artifacts from the distant past, ranging from stolen riches recovered by the Spanish conquistadors to huge sloth fossils.

There is one cenote at this location, known as the San Andrés site, as well as a well and cenote that has since dried up called a rejoyada. At a depth of roughly 50 meters, researchers uncovered human skeletal remains, pottery, and mural artwork in the well (164 feet). They discovered a mural dated from 1200-1500 CE, a ceremonial slab of granite, a ritual knife, charcoal, and at least 40 pots that seemed to have been broken in a ceremony within the rejoyada’s tunnels. These artifacts clearly show that these geological features were used for ceremonies and had spiritual significance.

“Not only because of the purposefully fractured pottery but also because of the traces of charcoal that show their exposure to fire and the manner they stacked stones on top of them to hide them since they did not, they are the product of landslides,” says the researcher. Helena Barba Meinecke, the head of the INAS’s Sub-Directorate of Underwater Archeology’s Yucatan Peninsula Office, stated in a statement.