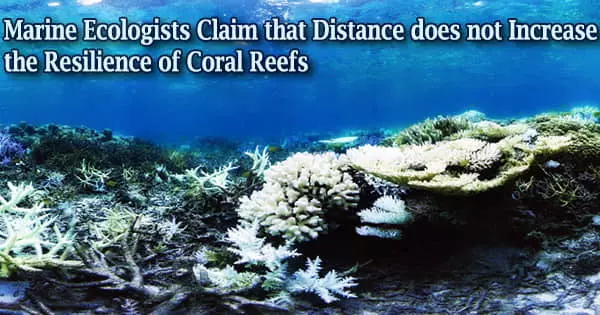

There is a widely accepted theory that claims coral reefs’ resistance to human impact is correlated with their isolation from human activity. Corals are more resilient to disturbances the further removed they are from people.

“The idea is that these coral reefs might serve as arks, that they could harbor biodiversity and intact ecosystems,” said UC Santa Barbara marine ecologist Adrian Stier of these ancient and fragile colonial organisms, most of which are under threat both locally, as from destructive fishing practices, and globally, as from ocean warming and acidification. “The hope is that these isolated areas might serve as a safe haven and, in the future, potentially repopulate areas that have been degraded.”

But when Stier and his colleagues tested that theory, they discovered it wasn’t true. No matter how far away some coral colonies were, on the whole, they didn’t show any stronger resistance to sudden disruptions than reefs with more pronounced human influence.

Additionally, there is some evidence that suggests human development-rich regions may recover from disturbances more quickly than their less developed, more remote equivalents.

“As an ecophysiologist, I’m usually studying how one individual coral or a population of corals responds to stress,” said lead author Justin Baumann, a marine biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and also at Bowdoin College in Maine.

“This study was a chance to zoom out and think globally about what drives coral resilience at much larger spatial scales and to really explore relationships between human influence and resilience globally.”

Their results are published in the journal Global Change Biology.

People and Corals

According to Stier, the researchers’ findings have important implications for managing and conserving coral reefs since they refute the widely-held belief that humans generally harm ecosystems.

“I got really curious about that idea, because after working regularly for the past 15 years on coral reefs, I’ve seen these big changes happen to coral reefs seeing corals die, big thermal events, lots and lots of mortality,” he said.

It’s important for us to consider sustainably managing fisheries in an equitable way, and it’s important for us to think about land pollution in the ocean. But we can’t rely on local management and preservation of remote areas to be this silver bullet that’s going to be our safeguard.

Adrian Stier

He has, however, also witnessed incredible recoveries, such as those that occurred around the island of Mo’orea in French Polynesia approximately ten years ago after a sea star epidemic severely damaged the coral reef habitats there, which the local populace greatly relies upon for both food and revenue. Stier was shocked to see the natural groups that depend on corals for food and storm protection were thriving, contrary to what they had anticipated.

“Over the past 10 years or so, we’ve seen some of these ecosystems recover and evolve. In some areas corals have come back and repopulated the reef in an incredible way,” Stier said.

So if an area with a heavy human presence can regain its coral reefs, does remoteness really promote resilience?

The researchers analyzed data from studies that tracked coral resilience and recovery after significant disturbances in numerous locations across the world, including the Caribbean Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the west and east Pacific Oceans, to find out. Between isolated, protected areas and those with higher levels of anthropogenic activity, coral resilience “varied tremendously.”

“Some places get knocked down and stay down and other places get knocked down and get back up,” Stier said. “As scientists, we’re still trying to figure out what underlies that capacity to bounce back for some systems and not others.”

Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that resilience was “positively associated with human impact” in some areas. One possibility for this illogical scenario is that the disruptions may have caused one coral species to be replaced by another.

“One reason we may be seeing higher resilience associated with higher human influence is a shift in coral population from competitive dominants to stress-tolerant and weedy genera due to previous disturbances,” Baumann said. “This shift, which is widely documented, can result in more coral cover, but loss of function on a reef.”

Additionally, they discovered that while some factors, such as pre-disturbance coral cover or co-occurring disturbances, influenced coral’s capacity to withstand or recover from disturbances, other factors, such as recovery time, travel distance to the nearest human population, or the presence of marine protected areas, had no bearing on estimates of recovery.

But the researchers are keen to note that this does not mean we shouldn’t continue to strive to manage human influence.

“It’s important for us to consider sustainably managing fisheries in an equitable way, and it’s important for us to think about land pollution in the ocean,” Stier said. “But we can’t rely on local management and preservation of remote areas to be this silver bullet that’s going to be our safeguard.”

The environments, animals, and people that live there depend on numerous attempts to protect local ecosystems and manage human influence. However, when considering coral reefs, we often focus on regional management strategies, such as fishing restrictions and marine protected zones.

“Those are great and needed, but we’ve seen again and again that globally it is climate change that is responsible for the brunt of the damage,” Baumann said. “We desperately need global scale decreases in greenhouse gas emissions likely to net zero to mitigate this stress.”

According to Lily Zhao, a UCSB graduate student researcher who studies social and ecological systems and is one of the authors of this study, such a global approach would necessitate a change in how coral reefs are managed, ideally in a way that distributes the work of conservation more equitably between the often poorer nations that are more acutely feeling the effects of global warming-driven marine events and the richer countries that contribute the majority of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

“Marine conservation has a history of using spatial exclusion and protected-area designations to separate local communities from their reefs and culture, often in ways that have benefited white people,” Zhao said.

“While international conservation practices are improving, it is still common for Western institutions and funding agencies to tell communities in the tropics how to manage their reefs using power or money.”

“Our findings allude to the idea that even if we removed local human stressors from a lot of these reefs, it still wouldn’t be enough,” she added. “To protect coral reefs, I think we should be spending less time telling coral reef dependent nations what to do with their resources and more time supporting their adaptation and advocating for drastic emissions reductions from the high-income countries that have caused the climate crisis.”