The time it would take for evolution to replace Madagascar’s endangered mammals would depend on a number of factors, including the rate of evolutionary change, the size of the populations of the endangered species, and the availability of suitable habitats. In general, the rate of evolutionary change is slow, and it can take many millions of years for new species to evolve.

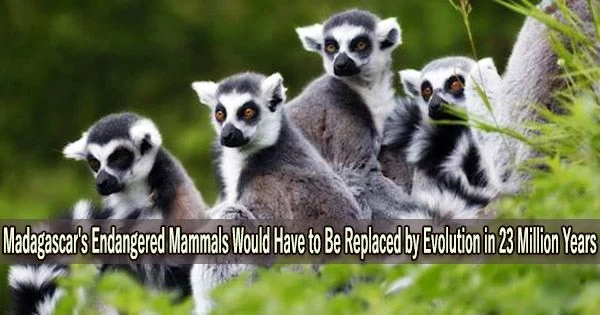

Madagascar is in many ways a biologist’s paradise, a live demonstration of how isolation on an island can lead to evolution. There are about 90% of flora and animals that are unique to that area.

But because of habitat loss, excessive hunting, and climate change, many flora and animals are in grave danger. More than 120 of the island’s 219 recognized animal species, including 109 species of lemurs, are under risk of extinction.

A recent study published in Nature Communications looked at how long it took Madagascar’s special modern mammal species to emerge and calculated how long it would take for a similar complex set of new mammal species to evolve in their place if the endangered ones went extinct. The results showed that it would take 23 million years, which is much longer than scientists have found for any other island. Simply put, that is extremely bad news.

“It’s abundantly clear that there are whole lineages of unique mammals that only occur on Madagascar that have either gone extinct or are on the verge of extinction, and if immediate action isn’t taken, Madagascar is going to lose 23 million years of evolutionary history of mammals, which means whole lineages unique to the face of the Earth will never exist again,” says Steve Goodman, MacArthur Field Biologist at Chicago’s Field Museum and Scientific Officer at Association Vahatra in Antananarivo, Madagascar, and one of the paper’s authors.

Madagascar is the world’s fifth-largest island, about the size of France, but “in terms of all the different ecosystems present on Madagascar, it’s less like an island and more like a mini-continent,” says Goodman.

It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is. These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective.

Luis Valente

The plants and animals in Madagascar have gone along their own evolutionary pathways, cut off from the rest of the globe, in the 150 million years since it separated from the African continent and the 80 million since it split from India.

Many of Madagascar’s endangered mammals are also facing threats from introduced species, such as predators and disease-carrying animals, which can further reduce their populations and limit their ability to recover.

Due to Madagascar’s diversity of habitats, which range from lowland deserts to mountainous rainforests, and smaller gene pool, mammals there underwent speciation much more swiftly than their counterparts on the continent.

However, this extraordinary biodiversity has a price: extinction and evolution are both accelerated on islands. Smaller populations that have evolved to inhabit certain, isolated habitat regions are more susceptible to extinction, and once gone, they’re gone forever.

More than half of the mammals on Madagascar are included on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, aka the IUCN Red List. The main causes of the extinction of these creatures over the past 200 years have been human activities, particularly habitat degradation and overhunting.

Goodman was part of an international team of scientists from Madagascar, Europe, and the United States who worked together to investigate the imminent extinction of Madagascar’s endangered creatures. They built a dataset of every known mammal species to coexist with humans on Madagascar for the last 2,500 years. (Humans have lived on the island, perhaps intermittently, for the past 10,000 years, but have remained constant there for the last 2,500.)

The scientists listed the 219 mammal species that are currently known to exist as well as an additional 30 species that have vanished over the past 2,000 years, including a gorilla-sized lemur that vanished between 500 and 2,000 years ago.

The researchers constructed genetic family trees to determine how these species are connected to one another and how long it took them to evolve from their numerous common ancestors using this dataset of all known Malagasy mammals that interacted with humans.

The scientists were then able to extrapolate how long it would take for evolution to “replace” all of the endangered mammals if they go extinct based on how long it took for this amount of diversification to arise.

It would take almost 3 million years to restore the diversity of land-dwelling mammals that have already become extinct over the previous 2,500 years. More concerningly, the models predicted that it would take 23 million years to reconstruct that level of diversity if all the mammals that are currently threatened with extinction did so.

That doesn’t imply that evolution will develop them if we simply wait another 23 million years if we allow all of the lemurs, tenrecs, fossas, and other distinctive Malagasy mammals go extinct.

“It would be simply impossible to recover them,” says Goodman. Instead, the model means that to achieve a similar level of evolutionary complexity, whatever those new species might look like, would take 23 million years.

Luis Valente, the study’s corresponding author, says he was surprised by this finding.

“It is much longer than what previous studies have found on other islands, such as New Zealand or the Caribbean,” says Valente, a biologist at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. “It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is. These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective.”

Instead, conservation efforts aimed at protecting and restoring the island’s remaining habitats and conserving its unique and threatened species are likely to be critical for ensuring their survival in the long term.

According to Goodman, Madagascar is at a tipping point for protecting its biodiversity.

“There is still a chance to fix things, but basically, we have about five years to really advance the conservation of Madagascar’s forests and the organisms that those forests hold,” he says.

This urgent conservation work is made difficult by inequality and political corruption that keeps land-use decisions out of the hands of most Malagasy people, says Goodman: “Madagascar’s biological crisis has nothing to do with biology. It has to do with socio-economics.”

But while the situation is dire, he says, “we can’t throw in the towel. We’re obliged to advance this cause as much as we can and try to make the world understand that it’s now or never.”