Liquidity Preference Theory is a model that proposes that an investor should demand a higher interest rate or premium on securities with long maturities that carry higher risk because, all else being equal, investors prefer cash or other highly liquid holdings. In macroeconomic theory, liquidity preference is defined as the demand for money when it is considered to be liquid. It depicts the relationship between the interest rate and the amount of money that the general public wishes to hold. John Maynard Keynes introduced the concept in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) to explain how interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for money. Liquidity preference, as defined by John Maynard Keynes, is the relationship between the amount of money the public wishes to hold and the interest rate.

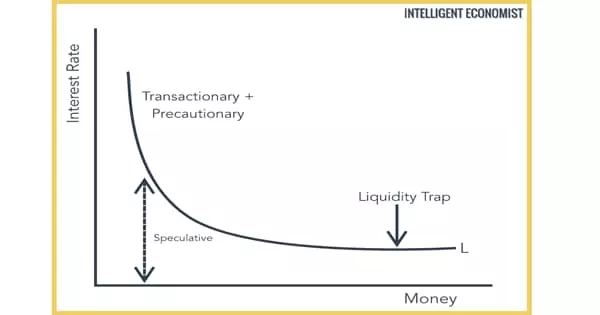

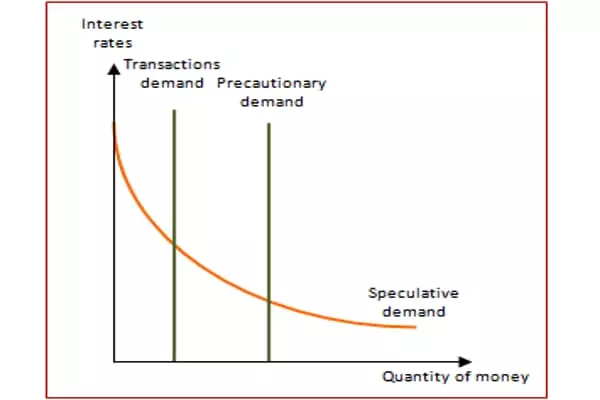

According to Keynes, the public keeps the money for three reasons: to have it on hand for ordinary transactions, to keep it as a reserve against unexpected expenses, and to use it for speculative purposes. He hypothesized that the amount held for the final purpose would vary inversely with the interest rate. The most important point to remember about Keynes’ theory is that at very low-interest rates, increases in the money supply will not encourage additional investment but will instead be absorbed by increases in people’s speculative balances. This will happen because the interest rate is too low to entice wealth holders to exchange their money for less liquid forms of wealth, and they anticipate interest rates rising in the future. In layman’s terms, this means that when money is demanded, it is not because someone wants to borrow money, but because someone wants to remain liquid.

The demand for money as an asset was theorized to be influenced by the interest lost by not holding bonds (here, the term “bonds” can be understood to also represent stocks and other less liquid assets in general, as well as government bonds). Interest rates, he claims, cannot be a reward for saving because if a person hoards his savings in cash, say, under his mattress, he will receive no interest despite the fact that he has refrained from consuming all of his current income.

Cash is widely regarded as the most liquid asset. According to the liquidity preference theory, interest rates on short-term securities are lower because investors are not willing to sacrifice liquidity for longer time frames than they are for medium or long-term securities. In the Keynesian analysis, interest is a reward for parting with liquidity rather than a reward for saving. Money, according to Keynes, is the most liquid asset. An asset’s liquidity is one of its characteristics. The faster an asset can be converted into money, the more liquid it is said to be. According to the theory, cash is the most widely accepted liquid asset, and more liquid investments can be easily cashed in for their full value.

Post-Keynesian analysis, which broadened the classification of liquid assets, has tended to relate the demand for money to a broader range of variables, including wealth and the various forms in which it is held, the yields of these various forms, the level of income, and the interest rate.