Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease, which is a type of dementia that affects memory, thinking and behavior. Eventually, symptoms become severe enough to obstruct daily activities. Language difficulties, disorientation (including a tendency to get lost easily), mood swings, a lack of desire, self-neglect, and behavioral problems can all be indicators of advanced Alzheimer’s disease.

Imagine your doctor tells you that, as part of your annual checkup, you’ll be given a brain scan to see if you are developing the amyloid plaques that cause Alzheimer’s disease. The scan shows you have the plaques.

Your doctor tells you not to worry; they’ll simply start you on a drug given twice a month that will remove the amyloid plaques before they damage your brain and prevent you from developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Sound like science fiction? It’s closer than you think.

A new study

According to a study that was simultaneously presented at the 2022 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease showed less decline in their cognition and function over 18 months if they were in the experimental drug lecanemab group than if they were in the placebo group. Let’s explore this study to learn what its findings indicate and how they might affect you or a close relative in the future.

How does the drug work?

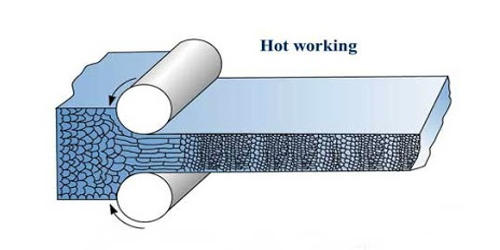

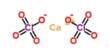

A monoclonal antibody called lecanemab was created in a lab to bind to amyloid protofibrils, which aggregate with other chemicals to form plaques in the brains of persons with Alzheimer’s disease.

The majority of scientists think tau tangles occur inside damaged brain cells as a result of plaque formation, which kills the cells. When lecanemab adheres to the plaque, your body’s immune system will react by removing the plaque since it will be mistaken for an outside invader.

Who benefited from the drug?

The 1795 participants in this study had early Alzheimer’s disease, defined as having evidence of amyloid plaques in their brain from either a brain scan or a lumbar puncture, and mild memory problems with either normal daily function (mild cognitive impairment) or difficulty with complicated daily tasks like paying bills and doing shopping (mild dementia).

From the race and ethnicity data presented at the conference, the majority of participants in this worldwide study were White (76.9 percent), with most others identifying as either Asian (16.9 percent) or Black (2.6 percent); 12.9 percent identified as Hispanic. The percentages of those identifying as Black and Hispanic were somewhat higher in the US enrolled participants, 4.5 percent and 22.5 percent, respectively.

How well does the drug work?

Comparing the lecanemab group to the placebo group, the lecanemab group had less deterioration on tests of daily functioning and cognition. On an 18-point clinical status scale, where scores between 0.5 and 6 indicate early Alzheimer’s disease, the difference in the primary outcome measure was 0.45.

Although a difference of 0.45 may not seem like much, the authors argue that it was greater than their aim of 0.37, indicating that this medicine had a clinically significant effect on these patients. Another way of looking at it is that that the drug reduced clinical decline by 27 percent.

Additional secondary end measures that assessed cognition and activities of daily living also revealed less deterioration in the lecanemab group, by 37% and 26%, respectively, compared to the primary outcome measure.

Since the medicine eliminated amyloid from the brain, an amyloid scan performed for diagnostic purposes would result in a negative reading, indicating that the subject did not have Alzheimer’s disease.

Most remarkable from my perspective were the data presented at the conference that lecanemab reduced both total tau (an indicator of the overall damage to the brain) and phosphorylated tau (which forms the tangles in Alzheimer’s disease). These amyloid and tau results suggest that lecanemab can, in a very real sense, reduce the amount of Alzheimer’s pathology that someone has in their brain.

What were the side effects?

44.7 percent of participants in the lecanemab group had an adverse event thought to be related to the study drug, compared to 22 percent of the placebo group. 12.6 percent of the lecanemab group developed brain swelling (called ARIA-E) compared with 1.7 percent of the placebo group. Some 14 percent of the lecanemab group developed a brain bleed compared to 7.7 percent of the placebo group (individuals with Alzheimer’s can develop small, spontaneous bleeds).

Headache was also somewhat more common in the lecanemab group (11.1 percent) compared to placebo (8.1 percent). The largest side effect was an infusion-related reaction, present in 26.4 percent of the lecanemab group versus 7.4 percent of the placebo group. Most participants were able to continue the infusions, such that, overall, only 6.9 percent of the lecanemab group discontinued the study drug, compared to 2.9 percent of the placebo group.

Six persons in the lecanemab group and seven in the placebo group passed away, with no differences between the groups. Two patients on lecanemab and blood thinners passed away from brain hemorrhages believed to be caused by the trial drug, even though they happened after the published study had ended.

What happens next?

The drug will next be reviewed by the FDA, possibly as early as January 2023. If approved, it will then be evaluated by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid, to see if Medicare will pay for it and the brain scans needed to confirm that Alzheimer’s disease is present.

What does the future hold?

Based on the results presented in this paper and the conference, I believe that the standard treatment of Alzheimer’s disease will change. If and when this drug becomes available, I will discuss the side effects, possible risks (including brain bleeds), and potential benefits with my patients who have early Alzheimer’s disease. Given the two recent deaths, I will probably advise against using lecanemab in people who are on blood thinners.

What about my science fiction scenario mentioned above?

Lecanemab is being tested in a research that is now enrolling participants who have amyloid plaques in their brains but no signs of memory loss in order to see if it can postpone or even reverse the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The future is almost here.