The Jāmeh Mosque of Isfahān or Jāme’ Mosque of Isfahān (Persian: مسجد جامع اصفهان; Masjid-e-Jāmeh Isfahān), also known as the Atiq Mosque (مسجد عتیق) and the Friday Mosque of Isfahān (مسجد جمعه), is a fusion of many architectural techniques from several historical eras. This mosque, located in Isfahan, Iran, 340 kilometers south of Tehran, is a major architectural manifestation of the Seljuk reign in Persia (1038-1118). From approximately 771 through the end of the 20th century, the mosque underwent continuous building, reconstruction, expansions, and repairs on the site.

The Seljuks, who arrived in Khwarazm and Transoxiana from Central Asia in the eleventh century, made Isfahan their capital in 1051. The Grand Bazaar of Isfahan is located on the mosque’s southwest wing. Tughril Beg’s capture of Isfahan enhanced the city’s prestige, as evidenced by the lavish architectural projects that represented the Seljuk empire’s might, the first of which was the Friday mosque. Since 2012, it has become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is one of Iran’s largest and most prominent Islamic architectural structures.

During the Sassanid era, this location was a fire temple before becoming a mosque. The building’s pre-Islamic origin has been confirmed by archeological findings, including a pillar bottom, although the exact foundation date is unknown. The Seljuks built their city center and square next to the existing Friday mosque, with their square being bounded on the north by the mosque’s elevation. The earliest mosque on this location was constructed about 771, during the reign of Al-Mansur, the Abbasid caliph.

The initial structure was rather modest, measuring 52 by 90 meters. It was made of mudbrick with stucco ornamentation in the Abbasid style of Syro-Mesopotamian architecture. Its ruins were discovered during research for the current mosque in the 1970s. As a result, many modern architectural historians consider the Friday Mosque to be the epitome of the Seljuk to early Safavid era, as well as the heart of the “pre-Abbas” city. The state of the mosque during Seljuk control is disputed by historians.

According to the best estimates, the construction of this structure began about 2000 years ago. Although additional evidence suggests that the mosque’s ultimate external appearance dates from the Seljuq Dynasty, it was renovated during the Safavid Dynasty. After the capture of Isfahan in 1050, it became the first capital of the Seljuk Empire. In 1086–87, the Seljuks altered the hypostyle building’s generally uniform and egalitarian shape by replacing the columns in front of the mihrab (on the mosque’s south side) with a huge domed area.

When Isfahan was conquered by Tughril Beg in 1051, the inhabitants of Isfahan were compelled to destroy the mosque “for the lack of wood,” according to famous historian and geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi. According to another report by Nasir-i-Khusrau, the mosque was “big and splendid” in 1052. Atiq Jameh Mosque is a superb example of many Iranian architectural styles in one location. At the time, the new dome was the biggest masonry dome in the Islamic world. It is supported on huge piers and has eight ribs.

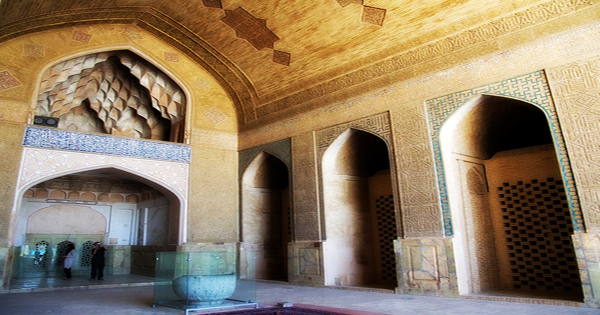

It also pioneered a novel form of squinch, consisting of a barrel vault atop two quarter-domes, which was quickly replicated in other mosques. The domed chamber might have been used as a maqsura, a prayer place designated for the Sultan and his entourage. The mosque was designed with four iwans (vaulted open rooms), each with a pair of gates facing each other. Each Iwan is adorned with stunning turquoise ceramics shaped like Muqarnas (niche-like cells).

The double-story arcade around the court (built about 1447) stands out among all the later restorations and additions to the mosque, replacing the previous one-story arcade and uniting the components of the court leading to the mosque’s different rooms. Taj al-Mulk, Nizam al-opponent, Mulk’s built another dome on the mosque’s north side in 1088–89. Although it was placed along the north-south axis, it was beyond the mosque’s limits. The dome is regarded as a masterpiece of Iranian architecture from the Middle Ages. Muqarnas’ shape (niche-like cells).

The two towers flanking the southwestern (qibla) iwan, and the enormous domes on the northeastern and southwestern sides of the complex rise above the horizon of Isfahan’s silhouette and serve as visual markers, are integrated organically into the urban fabric. Multiple points of entry to the mosque are possible because to the mosque’s incorporation into the city fabric, which is marked by shared walls that demarcate the border between the mosque’s territory and the neighboring buildings. Because of the blurring of borders and the lack of defined exterior walls of the ever-expanding mosque, it is impossible to circle the structure.

The mosque’s present entrance gate is placed in the southeast corner (southeast entrance portal). Most historians believe this was the main gate in the fourteenth century, possibly replacing one that no longer exists. This gate connects to the eastern wall’s top portion, which is closer to the southeast corner. Turn west and you’ll come across one of the world’s most beautiful Persian stuccoes. El-Jayto Mosque is the name of this section of a structure, and it is here that tourists can see the renowned Mehrab, which has a complex design.

The lower dome chamber walls are lighter and more beautiful, and the different components of the wall and dome are better vertically aligned, drawing one’s eyes upward. Another gate, still in use on the southwest side, comes from the reign of Shah Abbas in 1590-1. It links the city’s neighboring regions to the southwest and northwest arcade walls, allowing mobility between the city’s portions that were previously isolated due to the mosque’s installation.

After the mosque was destroyed by fire in 1121–22, the next significant change took place in the early 12th century. As previously stated, the (recently restored) court consists of a two-story arcade that functions as a two-dimensional screen and is adorned with glazed bricks in dark and light blue, white, and yellow that form floral and geometric designs. Except for the two bays flanking the eastern iwan, which rise higher than the other arches, the arches of the two-story arcade are symmetrically positioned around the four iwans situated in the middle of each of the four walls and are uniformly equal in height.

The courtyard’s southern iwan (leading to the mihrab) was bigger and more ornately decorated than the other iwans, with huge layers of muqarnas (a three-dimensional geometrical composition of niches). Furthermore, the northern part of the northwestern arcade is given a unique treatment by a massive gate that rises two storeys high, designating a winter mosque area. The remaining bays of the original hypostyle halls were restored with cross-ribbed vaults in addition to the four iwans. There are around 200 of these smaller vaults, each with a unique design and a wide range of geometric ornamentation.

The court’s four elevations are flat screens, but they also represent corridors leading to the mosque’s many sacred rooms and the city’s profane, everyday places. The mosque of today is a mash-up of several styles and times merged into one structure, the features of which are not usually clearly dated. Its perimeter is now completely entangled with the bazaar’s an old city’s surrounding constructions, leaving just a few distinct outside façades. The Isfahan Friday Mosque is considered a masterpiece of brick building by architectural historians. While it is comparable in size to mosques in Syria and Cordoba, it also has novel aspects that are widely regarded for their structural creativity and intricacy.