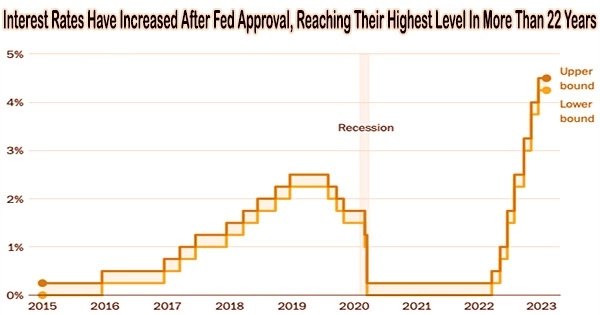

A highly anticipated interest rate increase by the Federal Reserve was approved on Wednesday, raising benchmark borrowing costs to their highest level in more than 22 years.

The Federal Open Market Committee of the central bank increased its funds rate by a quarter percentage point to a target range of 5.25%-5.5%, a move that financial markets had fully anticipated. The midpoint of that target range would be the highest level for the benchmark rate since early 2001.

The market was looking for indications that the increase might be the final before the Fed policymakers take a pause to assess the effects of the prior rate hikes on the economy. Markets have been pricing in a better-than-even chance that there won’t be any additional changes this year, despite officials’ statements at the June meeting that there would be two rate increases this year.

During a news conference, Chairman Jerome Powell said inflation has moderated somewhat since the middle of last year, but hitting the Fed’s 2% target “has a long way to go.” Still, he seemed to leave room to potentially hold rates steady at the Fed’s next meeting in September.

“I would say it’s certainly possible that we will raise funds again at the September meeting if the data warranted,” said Powell. “And I would also say it’s possible that we would choose to hold steady and we’re going to be making careful assessments, as I said, meeting by meeting.”

Powell said the FOMC will be assessing “the totality of the incoming data” as well as the implications for economic activity and inflation.

Markets initially bounced following the meeting but ended mixed. The Dow Jones Industrial Average continued its streak of higher closings, rising by 82 points, but the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite were little changed. Treasury yields moved lower.

I would say it’s certainly possible that we will raise funds again at the September meeting if the data warranted. And I would also say it’s possible that we would choose to hold steady and we’re going to be making careful assessments, as I said, meeting by meeting.

Jerome Powell

“It is time for the Fed to give the economy time to absorb the impact of past rate hikes,” said Joe Brusuelas, U.S. chief economist at RSM. “With the Fed’s latest rate increase of 25 basis points now in the books, we think that improvement in the underlying pace of inflation, cooler job creation and modest growth are creating the conditions where the Fed can effectively end its rate hike campaign.”

The post-meeting statement, though, offered only a vague reference to what will guide the FOMC’s future moves.

“The Committee will continue to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy,” the statement said in a line that was tweaked from the previous months’ communication. That echoes a data-dependent approach as opposed to a set schedule that virtually all central bank officials have embraced in recent public statements.

The hike received unanimous approval from voting committee members.

The only other change of note in the statement was an upgrade of economic growth to “moderate” from “modest” at the June meeting despite expectations for at least a mild recession ahead. The statement again described inflation as “elevated” and job gains as “robust.”

The increase is the 11th time the FOMC has raised rates in a tightening process that began in March 2022. The committee decided to skip the June meeting as it assessed the impact that the hikes have had.

Since then, Powell has said he still thinks inflation is too high, and in late June said he expected more “restriction” on monetary policy, a term that implies more rate increases.

The fed funds rate sets what banks charge each other for overnight lending. But it feeds through to many forms of consumer debt such as mortgages, credit cards, and auto and personal loans.

The Fed has not been this aggressive with rate hikes since the early 1980s, when it also was battling extraordinarily high inflation and a sputtering economy.

News lately on the inflation front has been encouraging. The consumer price index rose 3% on a 12-month basis in June, after running at a 9.1% rate a year ago. Consumers also are getting more optimistic about where prices are headed, with the latest University of Michigan sentiment survey pointing to an outlook for a 3.4% pace in the coming year.

However, CPI is running at a 4.8% rate when excluding food and energy. Moreover, the Cleveland Fed’s CPI tracker is indicating a 3.4% annual headline rate and 4.9% core rate in July. The Fed’s preferred measure, the personal consumption expenditures price index, rose 3.8% on headline and 4.6% on core for May.

All of those figures, while well below the worst levels of the current cycle, are running above the Fed’s 2% target.

Economic growth has been surprisingly resilient despite the rate hikes.

Second-quarter GDP growth is tracking at a 2.4% annualized rate, according to the Atlanta Fed. Many economists are still expecting a recession over the next 12 months, but those predictions so far have proved at least premature. GDP rose 2% in the first quarter following a large upward revision to initial estimates.

Employment also has held up remarkably well. Nonfarm payrolls have expanded by nearly 1.7 million in 2023, and the unemployment rate in June was a relatively benign 3.6% the same level as a year ago.

“It has been my view consistently, that … we will be able to achieve inflation moving back down to our target without the kind of really significant downturn that results in high levels of job losses,” Powell said.

The committee also said it would keep reducing the bond holdings on its balance sheet, which peaked at $9 trillion before the Fed started its quantitative tightening initiatives. This is in addition to raising interest rates. The balance sheet is now at $8.32 trillion as the Fed has allowed up to $95 billion a month in maturing bond proceeds to roll off.