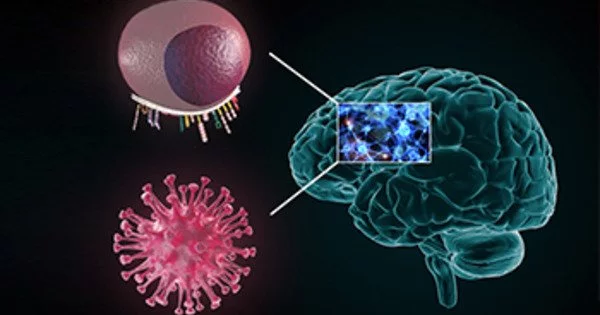

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, can infect cells in the brain and central nervous system. However, it does not “sleep” in a specific location in the brain. Instead, HIV can infect different types of cells in the brain, including macrophages and microglia, which are immune cells that play a role in defending the brain against infection. HIV can also infect astrocytes, which are support cells that help to maintain the health of neurons in the brain.

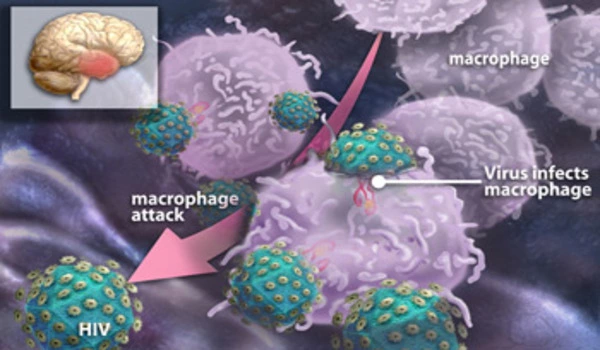

The human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1 can infect a variety of human tissues. The virus integrates its genome into the cellular genome and establishes persistent infections once inside the cells. The role of the host genome’s structure and organization in HIV-1 infection is not well understood. An international research team led by scientists from Heidelberg University Hospital and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) has now defined the insertion patterns of HIV-1 in the genome of microglia cells using a cell culture model based on brain immune microglia cells.

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is still an incurable disease in 99.9% of cases. This is because the virus “sleeps” in the genome of infected cells for a long time, rendering it invisible and inaccessible to the immune system and antiviral drugs. The pathways that HIV-1 uses to remain hidden in the host cell genome have primarily been studied in blood CD4+ T cells, the virus’s primary target cells.

HIV-1, on the other hand, is capable of infecting other immune cells in various organs, where it can establish stable reservoirs. The brain is one such viral haven, where the virus primarily infects microglia immune cells, causing neuroinflammation and symptoms of HIV-1 associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND).

We discovered a stronger correlation between a cellular chromatin factor and the sleeping virus phenotype by modeling HIV-1 infections of brain immune cells using microglia cell cultures. Our findings suggest that CTCF influences HIV-1 genomic insertion profiles in microglia, potentially contributing to the latent infection state.

Mona Rheinberger

Because studies in patients are limited in their ability to monitor the virus in the brain, questions about HIV-1 infection and replication in the brain have been difficult to resolve. Dr Marina Lusic of Heidelberg University Hospital and the DZIF led an international team that successfully developed HIV-1 infection models in human microglia cell cultures. The models’ development enabled researchers to investigate the insertion of the HIV-1 genome into microglia cells for the first time. The viral genome is silenced as a result of genomic insertion, resulting in the “sleeping virus” phenotype.

The researchers, who recently published their findings in the scientific journal Cell Reports, used the microglia cell models to determine HIV-1 integration sites and associate them with structural and regulatory elements of the chromatin.

“We discovered a stronger correlation between a cellular chromatin factor and the sleeping virus phenotype by modeling HIV-1 infections of brain immune cells using microglia cell cultures,” says Mona Rheinberger, the paper’s first author. “CTCF is one of the most important architectural proteins of the cellular genome, involved in chromatin folding and packaging within cells. Our findings suggest that CTCF influences HIV-1 genomic insertion profiles in microglia, potentially contributing to the latent infection state.”

“These studies in cell culture models are critical for understanding how the virus can be targeted in different parts of the body, where it can remain hidden or cause neurological disorders even under current therapeutic regimens,” Dr. Lusic concludes.

HIV can persist in the brain even when the virus is suppressed in other parts of the body, and this can lead to chronic inflammation and damage to the nervous system. This can cause a range of neurological symptoms, including cognitive impairment, motor deficits, and behavioral changes.

Overall, the location of HIV in the brain is not fixed and can vary depending on the type of cells that are infected and the stage of infection.