The current scientific consensus holds that the first human migrations from Asia to the Americas occurred during the Late Pleistocene epoch, when a land bridge known as Beringia connected modern-day Siberia (Russia) and Alaska (USA). This land bridge formed as a result of lower global sea levels caused by extensive glaciation in the northern hemisphere during the previous Ice Age.

A female lineage has been traced from northern coastal China to the Americas using mitochondrial DNA. The team discovered evidence of at least two migrations by combining contemporary and ancient mitochondrial DNA: one during the last ice age and one during the subsequent melting period. Another branch of the same lineage migrated to Japan around the same time as the second migration, which could explain Palaeolithic archaeological similarities between the Americas, China, and Japan. The findings were published in the journal Cell Reports.

“The Asian ancestry of Native Americans is more complicated than previously indicated,” says first author Yu-Chun Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “In addition to previously described ancestral sources from Siberia, Australo-Melanesia, and Southeast Asia, we show that northern coastal China also contributed to the gene pool of Native Americans.”

Though it was long assumed that Native Americans descended from Siberians who crossed the ephemeral land bridge of the Bering Strait, new genetic, geological, and archaeological evidence suggests that multiple waves of humans migrated to the Americas from various parts of Eurasia.

The Asian ancestry of Native Americans is more complicated than previously indicated. In addition to previously described ancestral sources from Siberia, Australo-Melanesia, and Southeast Asia, we show that northern coastal China also contributed to the gene pool of Native Americans.

Yu-Chun Li

To shed light on the history of Native Americans in Asia, a team of researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences followed the trail of an ancestral lineage that might link East Asian Paleolithic-age populations to founding populations in Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, and California. The lineage in question is present in mitochondrial DNA, which can be used to trace kinship through the female line.

The researchers combed through over 100,000 contemporary and 15,000 ancient DNA samples from across Eurasia to identify 216 contemporary and 39 ancient members of the rare lineage. The researchers were able to trace the lineage’s branching path by comparing the accumulated mutations, geographic locations, and carbon-dated ages of each of these individuals. They identified two migration events from northern coastal China to the Americas, and they believe that in both cases, the travelers arrived in America via the Pacific coast rather than the inland ice-free corridor (which would not have been open at the time).

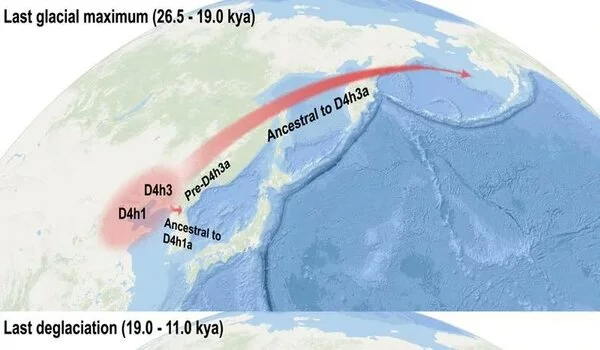

The first radiation event happened between 19,500 and 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheet coverage was at its peak and northern China was likely inhospitable to humans. The second radiation occurred between 19,000 and 11,500 years ago, during the subsequent deglaciation or melting period. At this time, there was a rapid increase in human populations, most likely due to improved climate, which may have fueled expansion into other geographical regions.

The researchers also uncovered an unexpected genetic link between Native Americans and Japanese people. During the deglaciation period, another group branched out from northern coastal China and traveled to Japan. “We were surprised to find that this ancestral source also contributed to the Japanese gene pool, especially the indigenous Ainus,” says Li.

This discovery contributes to the understanding of the Palaeolithic peoples of China, Japan, and the Americas. The three regions were particularly similar in how they fashioned stemmed projectile points for arrowheads and spears. “This suggests that the Pleistocene connection between the Americas, China, and Japan was not just cultural,” says senior author Qing-Peng Kong, an evolutionary geneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Though the study focused on mitochondrial DNA, evidence from Y chromosomal DNA suggests that Native Americans’ male ancestors lived in northern China around the same time as these female ancestors.

This study adds another piece to the puzzle of Native American ancestry, but many other details are still unknown. “The origins of several founder groups are still elusive or controversial,” Kong says. “Next, we intend to collect and investigate additional Eurasian lineages in order to obtain a more complete picture of Native American origins.”