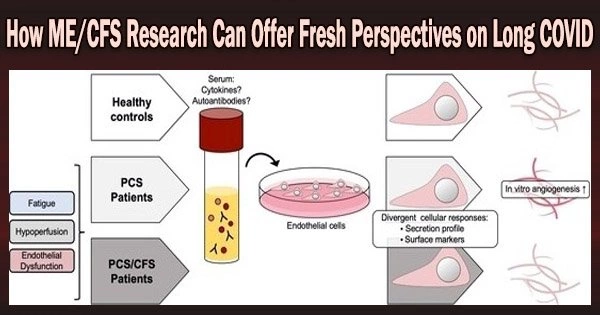

ME/CFS (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) and Long COVID (prolonged symptoms experienced by some COVID-19 patients) share some similar symptoms, such as fatigue and brain fog. Therefore, research on ME/CFS could potentially provide new insights into Long COVID and lead to better understanding and treatment of the latter.

On Monday, September 19, 2022, #MeAction Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and long COVID activists protested to address the crisis in the country with post-viral diseases. There have been many studies on ME/CFS conducted in labs around the world over the past 40 years, and individuals battling the current pandemic can learn a lot from their findings.

Although some lengthy COVID symptoms, including hair loss, are distinct, the majority of symptoms shared by those with long COVID and ME/CFS are similar. Most patients with ME/CFS also had a viral infection at the onset.

Given the parallels between these two disorders, by looking at what has happened over time with ME/CFS, we might be able to predict the prognosis for patients who have been diagnosed with extended COVID. We do know that the percentage of adults and children who first exhibit severe symptoms from these different diseases is large, but that it gradually tends to go down.

As an example, Hickie et al. (2006) launched a prospective study following adult patients from the time of acute infection with Epstein-Barr virus (glandular fever), Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), or Ross River virus (epidemic polyarthritis). The occurrence of post-infective fatigue syndrome decreased over time: 35% at six weeks, 27% at three months, 12% at six months, and 9% at 12 months.

Decreases in ME/CFS have also occurred in pediatric samples, such as Katz et al.’s (2009) investigation of youth following Infectious Mononucleosis. Therefore, we might anticipate symptom reductions for individuals with extended COVID.

However, for those who do not recover, it’s crucial to avoid casting doubt on the validity of patients’ ongoing symptoms because this trauma has happened far too frequently among ME/CFS patients.

In addition, there are lessons to be learned in how we gather data. As an example, in adult and pediatric community-based epidemiologic studies, from 90 to 95% of patients with ME/CFS does not know they have ME/CFS (Jason, Richman, et al., 1999; Jason, Katz, et al., 2020).

Therefore, it is not adequate to simply ask patients if they have ME/CFS because the majority have no knowledge what symptoms are in the accepted ME/CFS case definitions. This is because participants did not know the symptoms of ME/CFS.

A further issue with asking participants if they had received a diagnosis of ME/CFS is that many medical professionals struggle to make reliable diagnoses because they are unfamiliar with accepted case definitions for ME/CFS.

As has been learned by ME/CFS researchers, using psychometrically sound instruments with good reliability and validity is key to determining whether patients meet case definitions (Jason & Sunnquist, 2018).

How questions are asked is also worth examining. For a long time, data in the ME/CFS field only evaluated the occurrence of symptoms, but in the 1990s it became clear that the somatic symptoms required to meet the ME/CFS criteria were extremely prevalent in the general population (Jason, King, et al., 1999), and occurrence measures were therefore deemed to be too ambiguous. The next step was to evaluate how frequently the symptoms were present in the case definitions for ME/CFS.

Researchers ran across another conceptual issue, though, because ME/CFS and Major Depressive Disorder patients both experienced exhaustion on a frequent basis. In other words, one of the most prevalent mental health disorders (Major Depressive Disorder) could not be differentiated from ME/CFS using just measures of frequency.

However, when measures of severity were introduced, those with ME/CFS had significantly higher levels of fatigue severity than patients with Major Depressive Disorder (King & Jason, 2005). Therefore, it was possible to identify this crucial diagnostic distinction between ME/CFS and psychiatric illnesses by evaluating frequency and severity.

Post-exertional malaise has been considered to be possibly the most significant symptom in evaluating ME/CFS, as also shown in the Jason et al. (2015) study above. This symptom is now being recognized by influential PASC investigators, such as in Choutka, Jansari, Hornig, and Iwasaki’s (2022): “Studies should include features such as post-exertional symptom exacerbation and other characteristic symptoms and signs to better capture the complex clinical picture seen in PAISs.”

But rather than asking how frequently and with what severity this symptom occurs, the question is nearly always answered in a binary approach. The optimum threshold for determining whether a person has an illness or not (Watson et al. (2014) should be determined according to the frequency and severity of their symptoms.

The aforementioned concerns pertain to criterion variance, sensitivity, and specificity, and they are crucial for deciding how to most effectively identify ME/CFS patients in the ongoing lengthy COVID investigation. Utilizing tools with acceptable psychometric qualities and those that have been tested on ME/CFS samples before has its benefits.

Given the importance of determining which PASC patients meet these well-established criteria, a brief psychometric valid instrument should be used to assess critical ME/CFS symptoms and thus identify patients who meet ME/CFS case definitions (Sunnquist, Lazarus, & Jason, 2019).