The world has changed dramatically in the 50 years since the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was passed in December 1973. Two Ohio State University researchers were among a group of experts invited by the journal Science to discuss how the ESA has evolved and what its future may hold.

Tanya Berger-Wolf, faculty director of Ohio State’s Translational Data Analytics Institute, led a team that wrote about a “Sustainable, trustworthy, human-technology partnership.” Amy Ando, professor and chair of the Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote about “harnessing economics for effective implementation.”

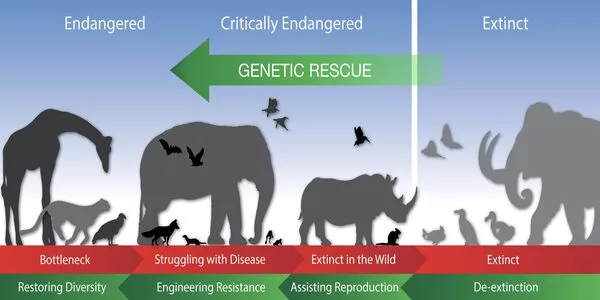

“We are in the midst of a mass extinction without even knowing what we are losing and how fast,” Berger-Wolf and her colleagues wrote. However, technology can assist in addressing this issue. They emphasize the importance of tools such as camera traps for surveying animal species and smartphone apps that allow citizen scientists to count insects, identify bird songs, and report plant observations, for example.

Economists have been working to understand how we can coordinate landowners where we don’t have to implement draconian land use regulations, but still protect habitat. That is a very promising tactic that can protect species and also reduce the cost to people of doing so.

Berger-Wolf

According to Berger-Wolf, who is also a professor of computer science and engineering, evolution, ecology, organismal biology, and electrical and computer engineering, new technology has enabled scientists to monitor animal and plant populations at scale for the first time. Finding new ways to extract all of the information from these new data sources is one challenge.

“But even with all this data, we are still monitoring only a tiny fraction of the biodiversity out in the world,” she went on to say. “Without that information, we don’t know what we have, how different species are doing, and whether our policies to protect endangered species are working.”

The most important thing, according to Berger-Wolf, is to keep humans involved in the process. Technology is required to connect data, different regions of the world, people to nature, and people to people.

“We don’t want to sever the connection between people and nature, we want to strengthen it,” she told me. “We can’t rely on technology to save the planet’s biodiversity.” It must be a deliberate collaboration between humans, technology, and AI.”

Economics should be another partner in the fight to save endangered species, Ando said.

“There’s this tendency to think that protecting endangered species is all about biology and ecology,” Ando said. “But various tools in economics are very helpful in making sure the work we do to implement the Endangered Species Act is successful. That is not always obvious to people.”

Bioeconomic research, for example, is a collaborative effort between economists and biologists to investigate how human behavior interacts with ecological processes and systems.

“We must account for feedback effects.” People take action, which alters the ecosystem and influences what people do,” she explained. “We need to capture those feedback effects.”

As a result, novel methods for protecting endangered species, such as “pop-up” habitat modification, may emerge. Ranchers, for example, can temporarily remove fences to allow elk to move freely while migrating. During shorebird migration, rice fields can be temporarily flooded to provide a rest and feeding area for the birds.

We can, in fact, “draw upon economics to optimize the timing, location and extent of temporary actions to maximize their net benefits to society,” Ando said in the journal Science. Another way economics can assist is by developing policies that protect species before they become so endangered that they require ESA protection.

A common issue is that multiple landowners will need to collaborate to protect threatened species’ habitat. However, if some landowners take action to protect a species, other landowners may believe they are not required to do so.

“Economists have been working to understand how we can coordinate landowners where we don’t have to implement draconian land use regulations, but still protect habitat,” he said. “That is a very promising tactic that can protect species and also reduce the cost to people of doing so.”