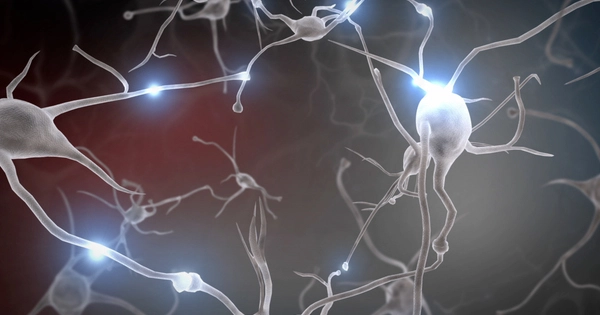

Speech from caregivers is important in shaping an infant’s brain development. Infants have highly plastic brains, which means they are highly adaptable and capable of forming new neural connections. Their language acquisition and cognitive development are heavily influenced by the quality and quantity of language input they receive during their early years of life.

A new study sheds light on how parents who talk to their infants help their children’s brain development. Scientists used imaging and audio recordings to link early language skills to caregiver speech, sending a message that parents can have a significant impact on their child’s linguistic development in ways that can be seen in brain scans.

A team led by a neurodevelopment researcher at the University of Texas at Dallas has discovered some of the most conclusive evidence yet that parents who talk to their infants improve their babies’ brain development.

The researchers used MRI and audio recordings to show that caregiver speech influences infant brain development in ways that benefit long-term language progress. The study’s corresponding author is Dr. Meghan Swanson, assistant professor of psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. It was published online and in the print edition of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience in June.

“This paper is a step toward understanding why children who hear more words go on to have better language skills and what process facilitates that mechanism,” Swanson said. “Ours is one of two new papers that are the first to show links between caregiver speech and how the brain’s white matter develops.”

This paper is a step toward understanding why children who hear more words go on to have better language skills and what process facilitates that mechanism. Ours is one of two new papers that are the first to show links between caregiver speech and how the brain’s white matter develops.

Dr. Meghan Swanson

White matter in the brain facilitates communication between various gray matter regions of the brain, where information processing occurs.

The Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS), a National Institutes of Health-funded Autism Center of Excellence project involving eight universities in the United States and Canada, as well as clinical sites in Seattle, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Minneapolis, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina, was used in the study. Home language recordings were collected at 9 months and again six months later, and MRIs were performed at 3 months, 6 months, and ages 1 and 2.

“This timing of home recordings was chosen because it straddles the emergence of words,” Swanson said. “We wanted to capture both this prelinguistic, babbling time frame, as well as a point after or near the emergence of talking.”

It has long been recognized that an infant’s home environment, particularly the quality of caregiver speech, has a direct influence on language acquisition, but the mechanisms underlying this are unknown. Swanson’s team focused on developing neurological pathways by imaging several areas of the brain’s white matter.

“The arcuate fasciculus is the fiber tract that everyone learns in neurobiology courses is essential to producing and understanding language, but that finding is based on adult brains,” Swanson explained. “In these children, we looked at other potentially meaningful fiber tracts as well, including the uncinate fasciculus, which has been linked to learning and memory.”

The researchers used the images to measure fractional anisotropy (FA). This metric for the freedom or restriction of water movement in the brain is used as a proxy for the progress of white matter development.

“As a fiber track matures, water movement becomes more restricted, and the brain’s structure becomes more coherent,” Swanson explains. “Because babies’ brains aren’t born with highly specialized brains, one might expect networks that support a given cognitive skill to start out more diffuse and then become more specialized.”

Swanson’s team discovered that infants who heard more words had lower FA values, indicating that their white matter structure developed more slowly. When the children started talking, they improved their linguistic performance. The findings of the study are consistent with other recent studies that show that slower maturation of white matter confers a cognitive advantage.

“As a brain matures, it becomes less plastic – networks get set in place. But from a neurobiological standpoint, infancy is unlike any other time. An infant brain seems to rely on a prolonged period of plasticity to learn certain skills,” Swanson said. “The results show a clear, striking negative association between FA and child vocalization.”

Sharnya Govindaraj, a cognition and neuroscience doctoral student and member of Swanson’s Baby Brain Lab, said she was surprised by the findings at first.

“At first, we didn’t know how to interpret these seemingly contradictory negative associations.” “The entire concept of neuroplasticity and learning new things had to fall into place,” she explained. “It also matters a lot which ability we’re looking at, because something like vision matures much earlier than language.”

Swanson was curious about how this relationship works for infants exposed to more than one language as the parent of a toddler in a bilingual household.

“Raising a bilingual child, it’s remarkable how she’s not confused by languages, and she knows who she can use which language with,” Swanson said. Swanson also expressed a greater appreciation and gratitude for what she, as a researcher, asks parents to do in her studies.

“When participants sign up, I’m asking them to commit to a year and a half,” she said. “Because of the commitment of all the parents in prior studies, I and others have the knowledge that allows us to communicate with our children in a way that supports their development.”