When you are experiencing stress, anxiety, or other forms of emotional discomfort, the endocannabinoid system can be triggered to help regulate and balance your body’s response. When you are stressed, your brain may release cannabinoid molecules to calm you down, activating the same brain receptors as THC derived from cannabis plants. However, the brain activity patterns and neuronal circuits governed by these brain-derived cannabis chemicals were not fully understood.

Under stress, the amygdala, a crucial emotional brain area, releases endogenous (the body’s own) cannabinoid molecules, which reduce the incoming stress signal from the hippocampus, a memory and emotion center in the brain, according to a recent Northwestern Medicine study in mice. These findings provide credence to the theory that endogenous cannabis compounds represent the body’s natural stress response.

Stress increases the likelihood of developing or aggravating psychiatric diseases ranging from generalized anxiety disorder and severe depression to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Understanding how the brain adapts to stress at the molecular, cellular, and circuit level could provide critical insight into how stress is translated into mood disorders and may reveal novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of stress-related disorders.

Dr. Sachi Patel

“Understanding how the brain adapts to stress at the molecular, cellular, and circuit level could provide critical insight into how stress is translated into mood disorders and may reveal novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of stress-related disorders,” said corresponding study author Dr. Sachi Patel, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine psychiatrist.

According to Patel, the study could indicate that defects in the brain’s endogenous cannabinoid signaling pathway could contribute to a higher susceptibility to developing stress-related psychiatric disorders such as depression and PTSD.

The study will be published in Cell Reports.

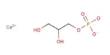

For the study, Northwestern scientists used a new protein sensor that can detect the presence of these cannabinoid molecules at specific brain synapses in real time to show that specific high-frequency patterns of amygdala activity can generate these molecules. The sensor also showed that these molecules were released as a result of several different types of stress in mice.

When scientists deleted the cannabinoid receptor type 1 target of these cannabinoids, the mice had a decreased ability to cope with stress and motivational deficiencies. When the receptor target of these endogenous cannabinoids at hippocampal-amygdala synapses was eliminated, mice displayed more sluggish and immobile responses to stress and had a decreased propensity to drink sweetened sucrose water following stress exposure. The latter finding may be related to anhedonia, or a decrease in pleasure, which is common in people suffering from stress-related diseases such as depression and PTSD.

One of the leading signaling systems that has been identified as a prominent drug-development candidate for stress-related psychiatric disorders is the endocannabinoid system, Patel said.

“Determining whether increasing levels of endogenous cannabinoids can be used as potential therapeutics for stress-related disorders is a logical next step from this study and our previous work,” said Patel, who is also the Lizzie Gilman Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at UCSF. “There are ongoing clinical trials in this area that may be able to answer this question in the near future.”

Farhana Yasmin, Amanda Morgan, and Keenan Johnson are among the other Northwestern authors.

The paper’s title reads: “Endocannabinoid release at ventral hippocampal-amygdala synapses regulates stress-induced behavioral adaptation.”