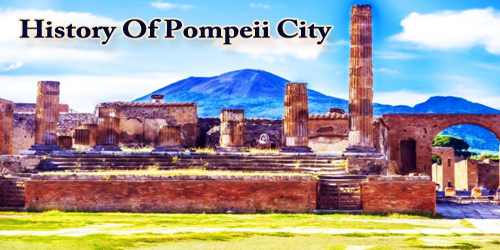

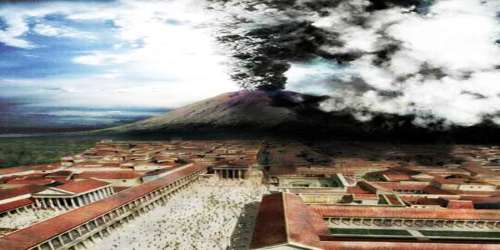

Pompeii (/pɒmˈpeɪ(i)/, Latin: pɔmˈpeːjjiː), Italian Pompei, preserved ancient Roman city in Campania, Italy, 14 miles (23 km) southeast of Naples, at the southeastern base of Mount Vesuvius. It was built on a spur formed by a prehistoric lava flow to the north of the mouth of the Sarnus (modern Sarno) River. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried under 4 to 6 m (13 to 20 ft) of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Torre Annunziata were collectively designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Pompeii is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Italy, with approximately 2.5 million visitors annually. Largely preserved under the ash, the excavated city offered a unique snapshot of Roman life, frozen at the moment it was buried, and an extraordinarily detailed insight into the everyday life of its inhabitants, although much of the evidence was lost in the early excavations. It was a wealthy town, enjoying many fine public buildings and luxurious private houses with lavish decorations, furnishings and works of art which were the main attractions for the early excavators. Organic remains, including wooden objects and human bodies, were entombed in the ash and decayed leaving voids which archaeologists found could be used as moulds to make plaster casts of unique and often gruesome figures in their final moments of life. The numerous graffiti carved on the walls and inside rooms provide a wealth of examples of the largely lost Vulgar Latin spoken colloquially at the time, contrasting with the formal language of the classical writers.

Pompeii supported between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants at the time of its destruction. The modern town (comune) of Pompei (pop. (2011) 25,440) lies to the east and contains the Basilica of Santa Maria del Rosario, a pilgrimage centre. After many excavations prior to 1960 that had uncovered most of the city but left it in decay, further major excavations were banned and instead they were limited to targeted, prioritised areas. In 2018, these led to new discoveries in some previously unexplored areas of the city.

Pompeii (pronounced – pɔmˈpɛjjiː) in Latin is a second declension plural noun (Pompeiī, -ōrum). According to Theodor Kraus, “The root of the word Pompeii would appear to be the Oscan word for the number five, pompe, which suggests that either the community consisted of five hamlets or perhaps it was settled by a family group (gens Pompeia).”

Life in Pompeii –

Greek settlers made the town part of the Hellenistic sphere in the 8th century B.C. An independently-minded town, Pompeii fell under the influence of Rome in the 2nd century B.C. and eventually the Bay of Naples became an attraction for wealthy vacationers from Rome who relished the Campania coastline.

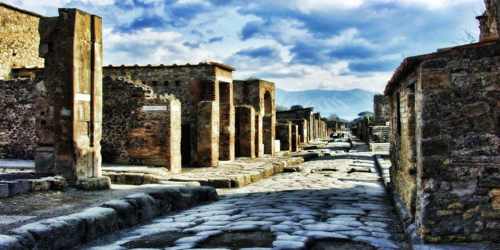

By the turn of the first century A.D., the town of Pompeii, located about five miles from the mountain, was a flourishing resort for Rome’s most distinguished citizens. Elegant houses and elaborate villas lined the paved streets. Tourists, townspeople and slaves bustled in and out of small factories and artisans’ shops, taverns and cafes, and brothels and bathhouses. People gathered in the 20,000-seat arena and lounged in the open-air squares and marketplaces. On the eve of that fateful eruption in 79 A.D., scholars estimate that there were about 12,000 people living in Pompeii and almost as many in the surrounding region.

Pompeii was built about 40 m above sea level on a coastal lava plateau created by earlier eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, (8 km (5.0 mi) distant). The plateau fell steeply to the south and partly the west and into the sea. Three sheets of sediment from large landslides lie on top of the lava, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall. The city bordered the coastline, though today it is 700 meters away. The mouth of the navigable Sarno River, adjacent to the city, was protected by lagoons and served early Greek and Phoenician sailors as a safe haven and port which was developed further by the Romans. Pompeii covered a total of 64 to 67 hectares (170 acres).

History –

Although best known for its Roman remains visible today dating from AD 79, it was built upon a substantial city dating from much earlier times. Expansion of the city from an early nucleus (the altstadt) accelerated already from 450 BC under the Greeks after the battle of Cumae.

It seems certain that Pompeii, Herculaneum, and nearby towns were first settled by Oscan-speaking descendants of the Neolithic inhabitants of Campania. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Oscan village of Pompeii, strategically located near the mouth of the Sarnus River, soon came under the influence of the cultured Greeks who had settled across the bay in the 8th century BCE. Greek influence was challenged, however, when the Etruscans came into Campania in the 7th century. The Etruscans’ influence remained strong until their sea power was destroyed by King Hieron I of Syracuse in a naval battle off Cumae in 474 BCE. A second period of Greek hegemony followed. Then, toward the end of the 5th century, the warlike Samnites, an Italic tribe, conquered Campania, and Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae became Samnite towns.

The period between about 450-375 BC witnessed large areas of the city being abandoned while important sanctuaries such as the Temple of Apollo show a sudden lack of votive material remains. The Samnites, people from the areas of Abruzzo and Molise, and allies of the Romans, conquered Greek Cumae between 423 and 420 BC and it is likely that all the surrounding territory, including Pompeii, was already conquered around 424 BC. The new rulers gradually imposed their architecture and enlarged the town.

From 343-341 BC in the Samnite Wars, the first Roman army entered the Campanian plain bringing with it the customs and traditions of Rome, and in the Roman Latin War from 340 BC the Samnites were faithful to Rome. Pompeii, although governed by the Samnites, entered the Roman orbit, to which it remained faithful even during the third Samnite war and in the war against Pyrrhus.

It is commonly known that in AD 63 a massive earthquake caused major damage in the town. Scholars now agree, however, that this was merely one in a series of earthquakes that shook Pompeii and the surrounding area in the years before AD 79, when Vesuvius erupted. It is clear that some buildings were repaired several times in this period.

In fact, Pompeii must have resembled a giant building site, with reconstruction work taking place in both public buildings and private houses. In the past scholars argued that the town was abandoned by the wealthy in this period and taken over by a mercantile class. These days we see the scale of rebuilding as a sign of massive investment in the city possibly sponsored by the emperor by inhabitants who sought to improve their urban environment.

In the 2nd century BC, Pompeii enriched itself by taking part in Rome’s conquest of the east as shown by a statue of Apollo in the Forum erected by Lucius Mummius in gratitude for their support in the sack of Corinth and the eastern campaigns. These riches enabled Pompeii to bloom and expand to its ultimate limits. The forum and many public and private buildings of high architectural quality were built, including the large theatre, the sanctuary to Jupiter, the Basilica, the Comitium, the Stabian Baths and a new two-story portico.

Pompeii joined the Italians in their revolt against Rome in this war and was besieged by the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 89 BCE. After the war, Pompeii, along with the rest of Italy south of the Po River, received Roman citizenship. However, as a punishment for Pompeii’s part in the war, a colony of Roman veterans was established there under Publius Sulla, the nephew of the Roman general. Latin replaced Oscan as the official language, and the city soon became Romanized in institutions, architecture, and culture.

In AD 59, there was a serious riot and bloodshed in the amphitheatre between Pompeians and Nucerians (which is recorded in a fresco) and which led the Roman senate to send the Praetorian Guard to restore order and to ban further events for a period of ten years. An earthquake in 62 CE did great damage in both Pompeii and Herculaneum. The cities had not yet recovered from this catastrophe when final destruction overcame them 17 years later.

An important field of current research concerns structures that were restored between the earthquake of 62 and the eruption. It was thought until recently that some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption but this has been shown to be doubtful as the evidence of missing forum statues and marble wall-veneers are most likely due to robbers after the city’s burial. The public buildings on the east side of the forum were largely restored and were even enhanced by beautiful marble veneers and other modifications to the architecture. By 79 Pompeii had a population of 20,000, which had prospered from the region’s renowned agricultural fertility and favorable location.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius –

Mount Vesuvius erupted on August 24, 79 CE. The Vesuvius volcano did not form overnight, of course. Vesuvius volcano is part of the Campanian volcanic arc that stretches along the convergence of the African and Eurasian tectonic plates on the Italian peninsula and had been erupting for thousands of years. In about 1780 B.C., for example, an unusually violent eruption (known today as the “Avellino eruption”) shot millions of tons of superheated lava, ash and rocks about 22 miles into the sky. That prehistoric catastrophe destroyed almost every village, house and farm within 15 miles of the mountain. The first phase was of pumice rain (lapilli) lasting about 18 hours, allowing most inhabitants to escape.

Just after midday on August 24, fragments of ash, pumice, and other volcanic debris began pouring down on Pompeii, quickly covering the city to a depth of more than 9 feet (3 metres) and causing the roofs of many houses to fall in. Surges of pyroclastic material and heated gas, known as nuées ardentes, reached the city walls on the morning of August 25 and soon asphyxiated those residents who had not been killed by falling debris. Additional pyroclastic flows and rains of ash followed, adding at least another 9 feet of debris and preserving in a pall of ash the bodies of the inhabitants who perished while taking shelter in their houses or trying to escape toward the coast or by the roads leading to Stabiae or Nuceria. Thus Pompeii remained buried under a layer of pumice stones and ash 19 to 23 feet (6 to 7 metres) deep. The city’s sudden burial served to protect it for the next 17 centuries from vandalism, looting, and the destructive effects of climate and weather.

Thirty-eight percent of the 1,044 were found in the ash fall deposits, the majority inside buildings. This differs from modern experience over the last 400 years when only around 4% of victims have been killed by ash falls during explosive eruptions. This cohort was possibly sheltering in buildings when they were overcome. The remaining 62% of bodies found at Pompeii lay in the pyroclastic surge deposits which probably killed them. It was initially believed that due to the state of the bodies found at Pompeii and the outline of clothes on the bodies it was unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause. Later studies indicated that during the fourth pyroclastic surge (the first surge to reach Pompeii) temperatures reached 300 °C (572 °F) which was enough to kill people in a fraction of a second. The contorted postures of bodies as if frozen in suspended action were not the effects of long agony, but of the cadaveric spasm, a consequence of heat shock on corpses. The heat was so intense that organs and blood were vaporised, and at least one victim’s brain was vitrified by the temperature.

Rediscovering Pompeii City –

The ruins at Pompeii were first discovered late in the 16th century by the architect Domenico Fontana. Herculaneum was discovered in 1709, and systematic excavation began there in 1738. Work did not begin at Pompeii until 1748, and in 1763 an inscription (“Rei publicae Pompeianorum”) was found that identified the site as Pompeii. The work at these towns in the mid-18th century marked the start of the modern science of archaeology.

Many scholars say that the excavation of Pompeii played a major role in the neo-Classical revival of the 18th century. Europe’s wealthiest and most fashionable families displayed art and reproductions of objects from the ruins, and drawings of Pompeii’s buildings helped shape the architectural trends of the era. For example, wealthy British families often built “Etruscan rooms” that mimicked those in Pompeiian villas.

A series of frescos were found in the atrium of the Praedium (aka ’Estate) of Julia Felix that seem to depict scenes of everyday life in the forum (the political centre of the Roman city). Twelve fragments of these frescoes survive: one depicts a beggar being offered something by a woman wearing a green tunic, and another shows a boy being whipped this sometimes has been considered evidence of the presence of a school in the forum area.

Other fragments show a man cleaning another man’s shoes, a cobbler, merchants displaying their wares to two women, and figures selling bread, fruit and vegetables, and what look like socks. In one scene a customer holds the hand of a child. Horses, mules, and carts, and possibly a chariot can be identified in other scenes.

In the 1920s Amedeo Maiuri excavated for the first time in older layers than that of 79 AD in order to learn about the settlement history. Questionable reconstruction was done in the 1980s and 1990s after the severe earthquake of 1980, which caused great destruction. Since then, except for targeted soundings and excavations, work was confined to the excavated areas. Further excavations on a large scale are not planned and today archaeologists try to reconstruct, to document and, above all, to stop the ever faster decay.

Under the Great Pompeii Project over 2.5 km of ancient walls are being relieved of danger of collapse by treating the unexcavated areas behind the street fronts in order to increase drainage and reduce the pressure of ground water and earth on the walls, a problem especially in the rainy season. As of August 2019, these excavations have resumed on unexcavated areas of Regio V.

Today, the excavation of Pompeii has been going on for almost three centuries, and scholars and tourists remain just as fascinated by the city’s eerie ruins as they were in the 18th century.

Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for over 250 years; it was on the Grand Tour. It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. To combat problems associated with tourism, the governing body for Pompeii, the Soprintendenza Archaeological di Pompei, have begun issuing new tickets that allow tourists to visit cities such as Herculaneum and Stabiae as well as the Villa Poppaea, to encourage visitors to see these sites and reduce pressure on Pompeii.

Information Sources: