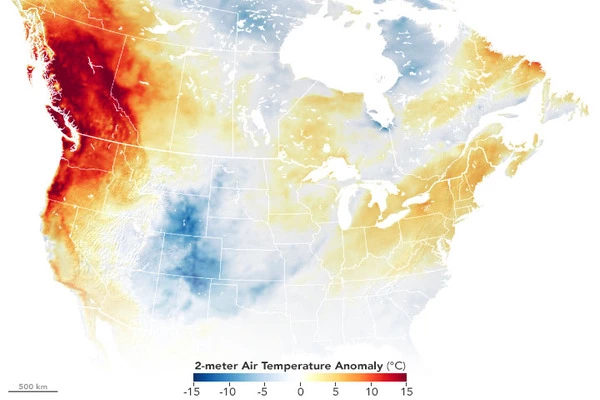

Heatwaves have fueled devastating wildfires across Europe, affecting millions of people. This year has already seen heat waves in a number of countries, ranging from India and Pakistan to Tunisia and Europe. Scientists believe that climate change is exacerbating heatwaves. This year’s extreme heat has engulfed nearly the entire Northern Hemisphere.

Europe is currently experiencing its third heat wave of the summer, which is fueling devastating wildfires and threatening millions of people. Portugal and Spain alone reported over 1,000 heat-related deaths on Sunday. Thousands of people fled wildfires in France. According to Sky News, one airport in the United Kingdom suspended flights after its runway melted, and another after its runway buckled in the heat. Wales experienced its warmest day on record.

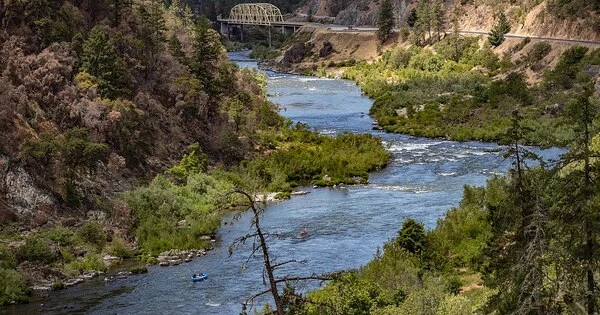

Rivers in the United States are becoming increasingly hot. According to a new study, the frequency of river and stream heat waves is increasing. Riverine heat waves, like marine heat waves, occur when water temperatures rise above their normal range for five days or more.

These very short, extreme changes in water temperature can quickly push organisms past their thermal tolerance. Compared with a gradual increase in temperature, sudden heat waves can have a greater impact on river-dwelling plants and animals, he says. Fish like salmon and trout are particularly sensitive to heat waves because the animals rely on cold water to get enough oxygen, regulate their body temperature and spawn correctly.

Dr. Tassone

Researchers compiled daily temperatures for 70 sites in rivers and streams across the United States using 26 years of US Geological Survey data, and then calculated how many days each site experienced a heat wave per year. The annual average number of heat wave days per river increased from 11 to 25 between 1996 and 2021, according to a study published in Limnology and Oceanography Letters.

The study is the first assessment of heat waves in rivers across the country, says Spencer Tassone, an ecosystem ecologist at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He and his colleagues tallied nearly 4,000 heat wave events jumping from 82 in 1996 to 198 in 2021 and amounting to over 35,000 heat wave days. The researchers found that the frequency of extreme heat increased at sites above reservoirs and in free-flowing conditions but not below reservoirs possibly because dams release cooler water downstream.

Most heat waves with temperatures the highest above typical ranges occurred outside of summer months between December and April, pointing to warmer wintertime conditions, Tassone says. Human-caused global warming plays a role in riverine heat waves, with heat waves partially tracking air temperatures — but other factors are probably also driving the trend. For example, less precipitation and lower water volume in rivers mean waterways warm up easier, the study says.

“These very short, extreme changes in water temperature can quickly push organisms past their thermal tolerance,” Tassone says. Compared with a gradual increase in temperature, sudden heat waves can have a greater impact on river-dwelling plants and animals, he says. Fish like salmon and trout are particularly sensitive to heat waves because the animals rely on cold water to get enough oxygen, regulate their body temperature and spawn correctly.

Heat has chemical consequences, according to hydrologist Sujay Kaushal of the University of Maryland in College Park, who was not involved in the study. Higher temperatures can hasten chemical reactions that pollute water, contributing to toxic algal blooms in some cases.

According to Kaushal, the research can be used as a springboard to help mitigate future heat waves, such as by increasing shade cover from trees or managing stormwater. Beaver dams show promise for lowering water temperatures in some rivers. “You can actually do something about it.”