The international research was launched at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (Coral CoE), which is based at James Cook University (JCU). According to co-author Professor Morgan Pratchett of JCU’s Coral CoE, the findings show that unless carbon dioxide emissions are drastically reduced, coral reef growth will be stunted.

“The threat posed by climate change to coral reefs is already very visible, as evidenced by recurring episodes of mass coral bleaching,” Prof Pratchett said. “However, changes in environmental conditions will have far-reaching consequences.”

According to co-author Professor Ryan Lowe of The University of Western Australia’s Coral CoE, modern coral reef structures reflect a balance between a diverse range of organisms that build reefs, not just corals. Coralline algae, a rock-hard alga that holds reefs together, is one example.

New research on the growth rates of coral reefs shows there is still a window of opportunity to save the world’s coral reefs—but time is running out.

“While the responses of individual reef organisms to climate change are becoming increasingly clear,” Prof Lowe said, “this study examines how the complex interactions between diverse communities of organisms responsible for maintaining present-day coral reefs will likely change reef structures in the future.”

Dr. Christopher Cornwall and Dr. Steeve Comeau (now at Victoria University of Wellington and Sorbonne Université CNRS Laboratoire d’Océanographie de Villefranche Sur Mer, respectively) calculated how coral reef growth is likely to respond to ocean acidification and warming under three different carbon dioxide scenarios: low, medium, and worst-case.

According to the findings, under an intermediate emissions scenario, some reefs may even grow to keep up with sea-level rise—but only for a short time. “Under the intermediate scenario, all reefs around the world will be eroding by the end of the century,” said JCU co-author Dr. Scott Smithers. “This will obviously have serious consequences for reefs, reef islands, and the people and other organisms that rely on coral reefs.”

The study provides broader projections of ocean warming and acidification, as well as their interaction, on coral reef net carbonate production.

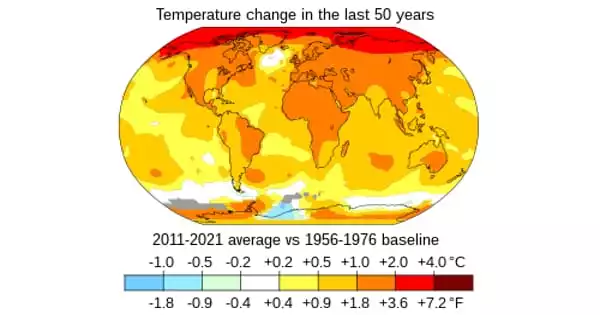

More marine heatwaves are caused by warming oceans, resulting in mass coral bleaching. The ability of calcifying corals to form their calcium carbonate skeletons, a process is known as ‘calcification,’ is affected by ocean acidification. Warming waters reduce calcification as well. Corals can lose their color as a result of global warming and environmental changes, limiting their ability to feed and reproduce. Scientists and policymakers are raising the alarm.

The study’s data set includes net calcification, bioerosion, and sediment dissolution rates measured or compiled from 233 different locations on 183 different reefs. The Atlantic Ocean had 49 percent of the reefs, the Indian Ocean had 39 percent, and the Pacific Ocean had 11 percent.

These were then modeled against three Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emission scenarios for low, medium, and high-impact ocean warming and acidification outcomes in 2050 and 2100.

Even in the low-impact case, the projections show that reef growth, or accretion, rates will be significantly reduced. “While 63 percent of reefs are expected to continue accreting by 2100 under the low-impact pathway, 94 percent are expected to erode by 2050 under the worst-case scenario,” Dr. Cornwall said. “And, under the medium and high-impact scenarios, no reef will continue to accrete at rates that match projected sea-level rise by 2100.”

‘If the world can drastically reduce carbon dioxide emissions, coral reef growth will be reduced, but many reefs will still be able to grow,’ says lead author Dr. Christopher Cornwall of New Zealand’s Victoria University of Wellington. ‘Some will even keep up with sea-level rise.’ Even if we fail to achieve those drastic reductions but stick to the intermediate emissions scenario, some coral reefs will continue to grow for a while longer, but by the end of the century, they will all be eroding. If we reach the worst-case scenario, all coral reefs will be eroding very soon.’

“Our research shows that changing environmental conditions pose a challenge to the growth of reef-building corals and other calcifying organisms, which are important in maintaining the structure of reef systems,” Prof Pratchett explained. “To save coral reefs, immediate and drastic reductions in global carbon emissions are required.”