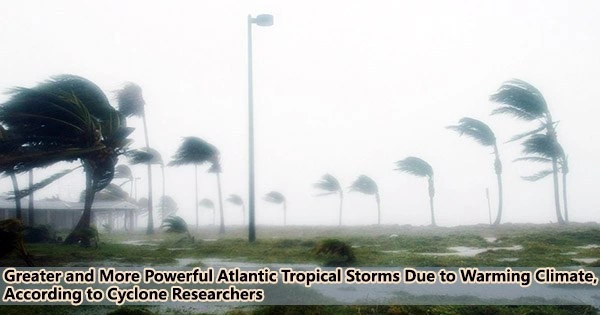

According to simulations employing a high-resolution global climate model, a warming climate could increase the number of tropical cyclones and their intensity in the North Atlantic, potentially leading to more and stronger hurricanes.

“Unfortunately, it’s not great news for people living in coastal regions,” said Christina Patricola, an Iowa State University assistant professor of geological and atmospheric sciences, an affiliate of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California and a study leader. “Atlantic hurricane seasons will become even more active in the future, and hurricanes will be even more intense.”

The Energy Exascale Earth System Model of the Department of Energy was used by the research team to run climate simulations, and the results showed that by the end of the century, the frequency of tropical cyclones during active North Atlantic hurricane seasons might rise by 66%. (Those seasons are typically characterized by La Niña conditions unusually cool surface water in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the positive phase of the Atlantic Meridional Mode warmer surface temperatures in the northern tropical Atlantic Ocean).

The projected numbers of tropical cyclones could increase by 34% during inactive North Atlantic hurricane seasons. (Inactive seasons generally occur during El Niño conditions with warmer surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the negative phase of the Atlantic Meridional Mode with cooler surface temperatures in the northern tropical Atlantic Ocean.)

Also, both the active and dormant storm seasons are predicted to see an increase in storm severity by the simulations.

The scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters recently published the findings. Ana C.T. Sena, an Iowa State postdoctoral research associate, is first author.

“Altogether, the co-occurring increase in (tropical cyclone) number and strength may lead to increased risk to the continental North Atlantic in the future climate,” the researchers wrote.

Patricola added: “Anything that can be done to curb greenhouse gas emissions could be helpful to reduce this risk.”

Tropical cyclone is a more generic term than hurricane. Hurricanes are relatively strong tropical cyclones.

Christina Patricola

Cyclone studies in Cyclone Country

Iowa State is home to the Cyclones and storm sirens are part of the hype at most athletic contests. Talk of the Cyclones is all over campus. But North Atlantic tropical cyclones? What are they?

“Tropical cyclone is a more generic term than hurricane,” Patricola said. “Hurricanes are relatively strong tropical cyclones.”

Exactly, says the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A low-pressure system that develops over tropical waters and has thunderstorms close to the center of its closed, cyclonic winds is referred to as a “tropical cyclone” in general.

When those rotating winds exceed 39 mph, the system becomes a named tropical storm. At 74-plus mph, it becomes a hurricane in the Atlantic and East Pacific oceans, a typhoon in the northern West Pacific.

Patricola grew up in the Northeast and can still tell stories about 1991’s Hurricane Bob.

“That was a big one for us in Massachusetts,” she said. “For me, it was very exciting. It really caught my interest.”

She was a Weather Channel fanatic through a lot of hurricanes in the mid-1990s. And that led to studies of geological and atmospheric sciences at Cornell University in New York, followed by atmospheric science and climate research at Texas A&M University and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Patricola joined the Iowa State faculty in August 2020.

Climate dynamics, climatic variability and change, extreme weather, atmosphere-ocean interactions, high-resolution climate modeling, land-atmosphere interactions, and paleoclimates are among Patricola’s scientific interests. And, tropical cyclones.

Why are tropical cyclone numbers so consistent?

A second study on tropical cyclones has just been released by Patricola and yet another team of partners. Derrick Danso, a postdoctoral research associate at Iowa State, is the first author on this one, which is also published in Geophysical Research Letters. The research investigates a potential explanation for the globally observed annual average of tropical cyclones.

Could it be that African Easterly Waves, low pressure systems over the Sahel region of North Africa that take moist tropical winds and raise them up into thunderclouds, are a key to that steady production of storms?

The researchers were able to exclude the African Easterly Waves and observe what transpired using regional model simulations. As it turned out, the models had little effect on the seasonal frequency of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic.

However, the strength of tropical cyclones increased, the peak season for storm formation switched from September to August, and the region of storm development shifted from the coast of North Africa to the Gulf of Mexico.

African Easterly Waves may not be able to predict the frequency of Atlantic tropical cyclones, but they do seem to have an impact on other key storm features, such as storm intensity and perhaps where they make landfall.

Both papers call for more study.

“We are,” Patricola said, “chipping away at the problem of predicting the number of tropical cyclones.”