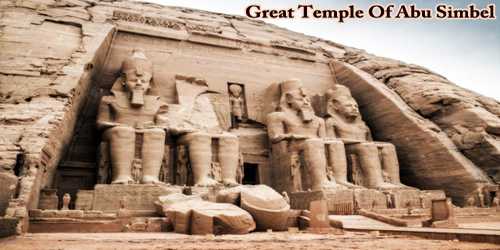

The Great Temple at Abu Simbel, which took about twenty years to build, was completed around year 24 of the reign of Ramesses the Great (which corresponds to 1265 BC). It was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, as well as to the deified Ramesses himself. It is generally considered the grandest and most beautiful of the temples commissioned during the reign of Ramesses II, and one of the most beautiful in Egypt. Four colossal (65 feet/20 meters high) statues of him sit in pairs flanking the entrance.

The head and torso of the statue to the left of the entrance fell during ancient times, probably the result of an earthquake. This temple faces the east, and Re-Horakhty, one manifestation of the sun god, is shown inside the niche directly above the entrance. The alignment of the temple is such that twice a year the sun’s rays reach into the innermost sanctuary to illuminate the seated statues of Ptah, Amun-Re, Ramesses II, and Re-Horakhty.

The temple was cut out of the sandstone cliffs above the Nile River in an area near the Second Cataract. When the High Dam was being constructed in the early 1960s, international cooperation assembled funds and technical expertise to move this temple to higher ground so that it would not be inundated by the waters of Lake Nasser.

Ozymandias is another name for Ramses II, the most powerful king of Egypt’s 19th dynasty. Ramses’ reign began a golden age in Egypt, brought on by his successful military campaigns into the Levant, Nubia, and Syria. Each of these victories was memorialized by new cities, elaborate temples, and massive statues erected all over his realm.

Among his many projects were the temples of Abu Simbel in Upper Egypt. Located in Nubia along the Nile River, they were carved out of solid rock. They commemorated a victory over the Hittites at Kadesh in 1275 B.C., and reminded Nubia of Egyptian dominance. Like many ancient structures, they eventually fell into disuse, true to the themes of “Ozymandias.” Sands moved in and buried the temples of Abu Simbel for millennia.

Entrance –

From the temple’s forecourt, a short flight of steps leads up to the terrace in front of the massive rock-cut facade, which is about 30m high and 35m wide. Guarding the entrance, three of the four famous colossal statues stare out across the water into eternity the inner left statue collapsed in antiquity and its upper body still lies on the ground. The statues, more than 20m high, are accompanied by smaller statues of the pharaoh’s mother, Queen Tuya, his wife Nefertari and some of his favorite children. Above the entrance, between the central throned colossi, is the figure of the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty.

The statue to the immediate left of the entrance was damaged in an earthquake, causing the head and torso to fall away; these fallen pieces were not restored to the statue during the relocation but placed at the statue’s feet in the positions originally found. Next to Ramesses’s legs are a number of other, smaller statues, none higher than the knees of the pharaoh, depicting: his chief wife, Nefertari Meritmut; his queen mother Mut-Tuy; his first two sons, Amun-her-khepeshef and Ramesses B; and his first six daughters: Bintanath, Baketmut, Nefertari, Meritamen, Nebettawy and Isetnofret.

The entrance doorway itself is surmounted by bas-relief images of the king worshipping the falcon-headed Ra Horakhty, whose statue stands in a large niche. Ra holds the hieroglyph user and a feather in his right hand, with Maat (the goddess of truth and justice) in his left; this is a cryptogram for Ramesses II’s throne name, User-Maat-Re.

Interior –

The inner part of the temple has the same triangular layout that most ancient Egyptian temples follow, with rooms decreasing in size from the entrance to the sanctuary. The temple is complex in structure and quite unusual because of its many side chambers. The hypostyle hall (sometimes also called a pronaos) is 18 m (59 ft) long and 16.7 m (55 ft) wide and is supported by eight huge Osirid pillars depicting the deified Ramesses linked to the god Osiris, the god of the Underworld, to indicate the everlasting nature of the pharaoh. The colossal statues along the left-hand wall bear the white crown of Upper Egypt, while those on the opposite side are wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt (pschent). The bas-reliefs on the walls of the pronaos depict battle scenes in the military campaigns that Ramesses waged. Much of the sculpture is given to the Battle of Kadesh, on the Orontes river in present-day Syria, in which the Egyptian king fought against the Hittites. The most famous relief shows the king on his chariot shooting arrows against his fleeing enemies, who are being taken, prisoner. Other scenes show Egyptian victories in Libya and Nubia.

The roof of the large hall is decorated with vultures, symbolizing the protective goddess Nekhbet, and is supported by eight columns, each fronted by an Osiride statue of Ramses II. Reliefs on the walls depict the pharaoh’s prowess in battle, trampling over his enemies and slaughtering them in front of the gods. On the north wall is a depiction of the famous Battle of Kadesh (c 1274 BC), in what is now Syria, where Ramses inspired his demoralized army so that they won the battle against the Hittites. The scene is dominated by a famous relief of Ramses in his chariot, shooting arrows at his fleeing enemies. Also visible is the Egyptian camp, walled off by its soldiers’ round-topped shields, and the fortified Hittite town, surrounded by the Orontes River.

The next hall, the four-columned vestibule where Ramses and Nefertari are shown in front of the gods and the solar barques, leads to the sacred sanctuary, where Ramses and the triad of gods of the Great Temple sit on their thrones. Here, on a black wall, are rock cut sculptures of four seated figures: Ra-Horakhty, the deified king Ramesses, and the gods Amun Ra and Ptah. Ra-Horakhty, Amun Ra and Ptah were the main divinities in that period and their cult centers were at Heliopolis, Thebes and Memphis respectively.

The original temple was aligned in such a way that each 21 February and 21 October, Ramses’ birthday and coronation day, the first rays of the rising sun moved across the hypostyle hall, through the vestibule and into the sanctuary, where they illuminate the figures of Ra-Horakhty, Ramses II and Amun. Ptah, to the left, was never supposed to be illuminated. Since the temples were moved, this phenomenon happens one day later.

Because of the accumulated drift of the Tropic of Cancer due to Earth’s axial precession over the past 3 millennia, the event’s date must have been different when the temple was built. This is compounded by the fact that the temple was relocated from its original setting, so the current alignment may not be as precise as the original one.

Rediscovery –

In 1813, archaeologists recovered Ramses’ temples from the desert, and their immortality seemed assured until 1960, when plans to dam the Nile threatened to submerge them and other ancient monuments in the region. To save them, Egypt sponsored a massive international effort to launch the most complex archaeological rescue mission of all time: to move entire sites to higher ground.

A well-known graffito inscribed in Greek on the left leg of the colossal seated statue of Ramesses II, on the south side of the entrance to the temple records that:

“When King Psammetichus (i.e., Psamtik II) came to Elephantine, this was written by those who sailed with Psammetichus the son of Theocles, and they came beyond Kerkis as far as the river permits. Those who spoke foreign tongues (Greek and Carians who also scratched their names on the monument) were led by Potasimto, the Egyptians by Amasis.”

Kerkis was located near the Fifth Cataract of the Nile “which stood well within the Cushite Kingdom.”

In 1963, after numerous ideas were proposed and rejected, it was decided that Ramses’s temples would be cut into more than a thousand blocks and relocated to a higher spot. The mission required complex infrastructure. A temporary dam was built around the site to keep it dry. A network of supply roads had to be laid, an electricity-generating station had to be installed, and accommodations had to be provided for the thousands of laborers involved in the project.

Dismantling concluded in April 1966. Reconstruction followed, and National Geographic magazine documented the colossal effort of excavating the new site, moving the blocks, and putting the pieces back together. After more than two years of painstaking work, Abu Simbel was inaugurated in its new, higher location on 22nd September 1968.

Information Sources: