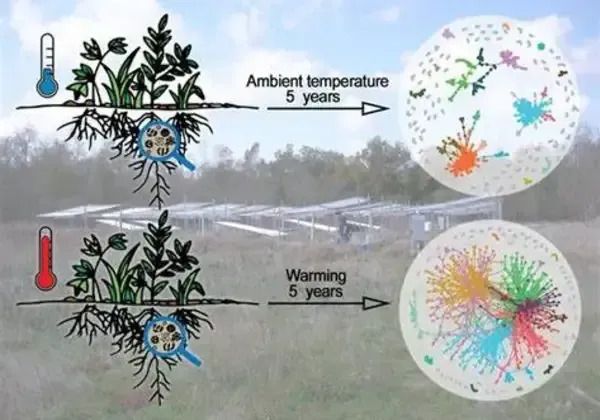

According to a new study conducted by researchers at the University of Vienna’s Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science (CeMESS), warmer soils support a greater diversity of active bacteria. The work, published in Science Advances, marks a substantial shift in our understanding of how microbial activity in soil affects the global carbon cycle and potential climate feedback mechanisms.

Until now, scientists assumed that greater soil temperatures accelerated microbial development, resulting in more carbon release into the sky. However, the higher release of carbon is produced by the activity of previously dormant microbes.

“Soils are Earth’s largest reservoir of organic carbon,” states Andreas Richter, lead author of the study and professor at the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science. Microorganisms silently dictate the global carbon cycle, breaking down this organic matter thereby releasing carbon dioxide. As temperatures rise — a guaranteed scenario under climate change- microbial communities are thought to emit more carbon dioxide, further accelerating climate change in a process known as soil carbon-climate feedback.

We saw that more than 50 years of consistent soil warming increased microbial growth at the community level. But remarkably, the growth rates of microbes in warmer soils were indistinguishable to those at normal temperatures.

Dennis Metze

“For decades, scientists have assumed that this response is driven by increased growth rates of individual microbial taxa in a warmer climate,” Richter said. In this study, researchers visited a subarctic grassland in Iceland that has experienced geothermal warming for over a half-century, resulting in higher soil temperatures than neighboring areas. By collecting soil cores and employing cutting-edge isotope probing techniques, the team discovered active bacterial species and compared their growth rates at ambient and enhanced temperatures, the latter being 6 °C higher.

“We saw that more than 50 years of consistent soil warming increased microbial growth at the community level,” says Dennis Metze, PhD student and primary author of the study. “But remarkably, the growth rates of microbes in warmer soils were indistinguishable to those at normal temperatures.” The pivotal difference lay in the bacterial diversity: Warmer soils harboured a more varied array of active microbial taxa.

Predicting soil microbial activities in a future climate

While global warming can have various impacts on ecosystems and microbial communities, it’s essential to approach such statements with caution and consider the broader context. The relationship between global warming and soil bacteria diversity is complex and can depend on several factors, including temperature, moisture, nutrient availability, and land use practices.

“Understanding the complexities of the soil microbiome’s reaction to climate change has been a considerable challenge, often rendering it a ‘black box’ in climate modeling,” adds Christina Kaiser, associate professor at the Centre.

This novel result goes beyond the typical focus on community-aggregated growth, paving the way for more precise forecasts of microbial activity and its effects on carbon cycling in the changing climatic scenario. This study’s findings shed light on the various microbial reactions to warming and are critical for anticipating the soil microbiome’s influence on future carbon dynamics.