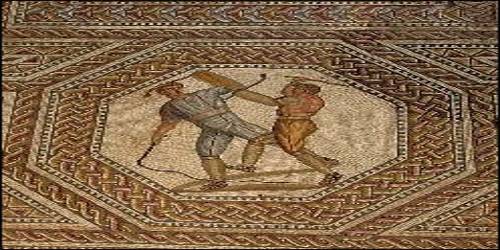

Gladiators in ancient Period

One of the most famous elements of Roman society and entertainment. A unique product of Rome and Italy, gladiators came to epitomize the socially decadent nature of the Romans, with their taste for blood sports. Gladiators emerged among the Etruscans as a form of the traditional blood sacrifice held at funerals, when teams of warriors dueled to the death. When the early Romans fell under the domination of Etruria, many prisoners of war were offered up in this manner, a ceremony repeated in 358 BCE, when 307 captives were sacrificed in the Tarquin Forum. Inevitably, the Romans accepted many Etruscan rituals; in 264 BCE, the family of M. Brutus solemnly celebrated his funeral with gladiatorial battles.

From that time on, burials honored by bouts between gladiators became both common and grand. The gladiatorial schools, the type of combatants and their place in society were all fully developed. The final aggrandizement of gladiators came in the last stages of the Republic, when candidates staged large shows for public enjoyment and political influence, culminating with the election of Julius Caesar as an aedile in 65 BCE. He held a massive celebration, complete with over 300 dueling pairs. Henceforth, the contests became an important part of the imperial control of the Roman mobs, satisfying the Romans’ thirst for action and directing their frustrations and energy.

Gladiatorial shows were not a major part of the ludi, the public games held many times throughout the year in Rome. Rather, the combats were staged privately, especially by the patronage of the ruling family. Rulers were expected to provide entertainments equal to the grandeur of their reigns and were careful not to disappoint the mobs. Augustus started the so-called extraordinary games, displays with no official function other than amusement for the people. Eight separate shows were put on in his name or in the names of his children. Claudius followed his example, entering into a shouting match with the contestants on one occasion.

Titus opened the Colosseum (ca. 80 CE) with elaborate ceremonies and a gladiatorial spectacle lasting 100 days. Trajan, celebrating in 107 his triumph in the Dacian Wars, used 5,000 pairs of gladiators in the rings. Trajan loved to mount displays, and his reign was noted for its shows. Hadrian, like Gaius Caligula, actually took part for a time in the sport, as did Caracalla and his brother Geta. Commodus, son of Marcus Aurelius, displayed such a passion for gladiatorial life-styles that the story was told that his true father, in fact, was one. He fought in the ring and seemed far happier in the presence of the other combatants. He was slain to deter him from entering the consulship of 193 with a parade from the gladiator barracks. Dio wrote in detail of his obsession for the arena.

By the fourth century CE, and with the rise of Constantine the Great, gladiators were vehemently opposed by Christians as being a part of the wide practice of paganism. Many earlier writers and political figures, such as Seneca, who epitomized the philosophical view, held that such exhibitions were monstrous and needlessly cruel. (The Christian bishop of Tagaste, Alypius, once watched gladiators and was disturbed to find himself caught up on the excitement of the carnage.) In the face of Christian leaders who were aware of the fact that martyrs of the faith had been slaughtered for centuries in the arenas, gladiators could do little to prevent the growing restrictions and then final abolishment. Constantine gave the Christians a taste of blood vengeance by throwing German prisoners to the wild animals, but he took steps in 326 to curtail the shows through the Edict of Berytus.

Such measures were only partially successful because of the popularity of the entertainment. Throughout the fourth century harsher laws were passed, until around 399, when Honorius ordered the last of the actual schools closed. The cause of this vigorous action by the emperors was the relentless writing and preaching of Christian officials. St. Augustine, St. John Chrysostom, Prudentius, and, earlier, Tertullian condemned the fighting. Public outrage was also turned against the gladiators, following the murder of the Eastern monk Telemachus by a crowd enraged at his interference in a match (held either in 391 or 404).

There had always been a large number of willing participants in the grim life of combat and death, which was viewed as a haven for the desperate. Candidates for the schools were originally found among slaves and captives; prisoners of war, with nothing to lose, joined. But the popularity of the sport soon demanded other avenues of supply. Slaves were bought and then condemned prisoners used, the damnati, as well as members of the lower classes, the humiliores. During the empire two other trends developed. First, many noblemen were sent by the various emperors into the ring to fight, for committing many, sometimes imaginary, crimes. Once, when Gaius Caligula fell ill, a courtier vowed to fight in the arena if he should recover. When Caligula returned to good health, he forced the courtier to fulfill his pledge, paying careful attention to his swordplay. The courtier survived the arena.

Later, the imperial citizens, freedmen, even members of high society, entered the class of the auctorati, those who abandoned themselves to the gladiatorial lifestyle for a wage, by giving an oath of service for a period of time. Changes in political or economic fortune also prompted this recklessness. Those reduced to poverty signed up to escape debtors and to administer to themselves a kind of purgation for profligate living. Gluttons, the so-called Apicians, would spend vast fortunes on banquets and lavish foods, go bankrupt and either kill themselves or become gladiators; in rare cases, Apician females would become fighting women.

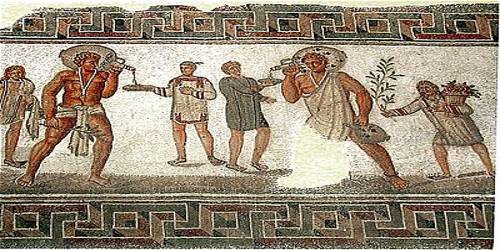

A lanista, or drill instructor, relentlessly exercised the gladiators in the schools. Gymnastics and strength building were first emphasized. The student then practiced with a wooden sword (lusoria arma) until proficient with it, and then progressed to harder training with a variety of weapons. This study continued until the gladiator was master of them all. He then chose his special weapon and style, assuming the character that would remain uniquely his until his death or his retirement. Specialists instructed each fighter on a specific weapon.

There were five classes of gladiators: eques, essedarii, Galli, Thraeces, and etiarii. The eques was a horseman, the essedarii were charioteers and the Galli were heavy fighters, further divided into several types. The Mirmillos (myrmillones) and Samnites fought with short swords, long shields and large helmets. A secutor was a variation on the Samnite, although in later years the Greek term hoplomachi was applied to all heavy fighters. The Mirmillo (identified by the fish crest on his helmet) was often put into combat against the lighter armed but mobile Thracians. Thracians carried long scimitars and bucklers or smaller shields. Their armor was normally tight leather (fasciae), fastened around a leg. The least protected of all, but perhaps the most famous, were the retiarii or the net-and-trident duelers. They wore no armor at all, holding instead a net and a trident. Quickness was their only hope, for once cornered or separated from their weapons, they were easy prey for the heavier classes. Gladiators learned never to rely upon the mercy of the spectators to save them.

Information Source: